(JTA) — Two years ago, a poll on Twitter tried to settle once and for all how to refer to the corner of the social media platform where Jews conversed. “Jwitter” got two thirds of the 525 votes, with the rest falling to “Jtwitter.”

Whatever they call it, the Jewish users of Twitter have used the site over the past 15 years to do everything from trade jokes, fight over food and contend over abiding divisions in Jewish communities, often in terms that would be hard to understand for anyone who’s not versed in Jewish tradition, texts and pop culture references. Their discourse summoned into existence crowd-sourced Shabbat reading lists, revelations by synagogue staffers and even an alternate reality in which Jews are the majority population.

Now the thousands of Twitter users who stick to niche Jewish content are questioning their relationship to the platform amid sweeping turmoil following its acquisition last week by the billionaire entrepreneur and provocateur Elon Musk. Musk has swiftly made steep layoffs and abrupt changes to moderation and authentication rules, all while tweeting crass and controversial content himself. The situation has emboldened antisemites on the platform and caused the Anti-Defamation League to call for a boycott.

Taken together, many Jewish Twitter users, especially the ones highly involved in these micro-communities, have started to question whether the platform remains a good place for the Jews at all. Some are signing off, while others are standing firm. Many are mourning the potential disruption to the community they have valued while questioning the conflict and incivility they experienced along the way.

“I don’t know if it ever got resolved,” Abraham Josephine Riesman, a Jewish writer who has been active on Jewish Twitter for several years, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency about the debate over the niche’s name. “And now it’s all going to just be destroyed before we come to a resolution.”

We spoke to a dozen longtime participants on Jewish Twitter about what Jwitter/Jtwitter was (and wasn’t) and what they foresee for the future of Jewish conversation online. Here’s what they told us.

Emily Tamkin (@emilyctamkin), author of “Bad Jews” and “The Influence of Soros”

Snapshot of Twitter bio: “Senior Editor, US, @newstatesman.”

I think the speed of the decline is still to be determined and depends on what Musk and company actually manage to roll out (or don’t), but the day of Twitter as sort of “urgent agora” is gone.

Like every other part of Twitter, Jwitter/Jtwitter could be maddening and mean. On Inauguration Day in 2021, I tweeted a joke that it was a big day for American Jews, what with Bernie Sanders’ mittens and Doug Emhoff. Some people saw this and decided to let me know that I was everything wrong with American Jewishness. I won’t miss moments like that. I won’t miss bad faith attacks or hyperbole. There were debates that I should have stayed out of that I involved myself in, and ones where I feel now that I should have said something and didn’t, and I won’t miss either of those feelings. And I will not miss watching people argue back and forth about things they are never going to resolve, and certainly not on Twitter.

But on the other hand, there are people I now consider myself friendly with whom I’d never have met, and people I’m now aware of about whom I had never heard before. I learned recipes and traditions and got book and music recommendations, but, more than that, I learned different — and Jewish — ways of thinking about the world. Even those endless debates were, in a way, a privilege. I got to watch Jewish thinkers hash out things that mattered to them. I know I just said in the previous paragraph that I won’t miss that, but a different part of me will, and already does.

Shoshana Gottlieb (@thetonightsho), Jewish content creator

Twitter bio: “i teach, i write, i watch tv, i’m jewish”

Maybe I’m really naive, but I don’t think the Musk takeover is going to irrevocably change Twitter. I lived through Tumblr getting sold and resold like five times. People came and people went, but surrounding myself with the right community meant that I never really felt the huge changes. And my Twitter experience is the same: I am careful with who I follow, I am liberal with the block button. I create a space that is fun and fulfilling, otherwise what’s the point of being there?

Leaving the website isn’t the huge “get effed” some of us think it is. Leaving the website simply means there is no Jewish voice anymore, no virtual community for those who seek it, nobody pushing back against harmful rhetoric. There will always be antisemites, such is the nature of the world. Only we get to decide if Jewish community remains.

If I’m wrong, if it becomes impossible to use or harassment kicks up to an unbearable notch, I’ll be sad to see it go. I’ll miss the jokes and gags, but I’ll also miss the micro-Torah, 280-character shiurim that make me think and rethink for days on end. I’ll miss the extreme Jewish geography (one time I posted my grandfather’s Hebrew name and someone DM’d me that he knew my uncle and cousins). I’ll miss being part of a larger conversation with people infinitely more interesting and impressive than I am.

Anthony Russell (@mordkhezvi), Yiddish opera singer

Twitter bio: “So, your bubbe was nattering on about some black guy who sings in Yiddish. It’s me”

Wading into the troubled waters of JTwitter has always given me the vertiginous feeling of corresponding from the penthouse of the tower of Babel; collapse is imminent and we yet here we are, muttering wryly in each other’s general direction.

At its best, JTwitter has been a source of humor, information, learning, organization, solidarity, spiritual, emotional and communal support; at its worst — especially when one is a Jew of Color, it’s never very far behind — it has been the site of ignorance, rancor, marginalization, racism and fear-mongering, a public hashing-out of some of the most contentious areas of Jewishness that cry out for patience, understanding, goodwill, justice and a desire for resolution. Unfortunately, at a limit of 280 characters, those things usually don’t make the cut.

Does this make JTwitter different from any other communally organized portions of the platform? I suppose not, but we actually have a phrase for what it should be fervently trying to avoid: sinat chinam — senseless hatred.’

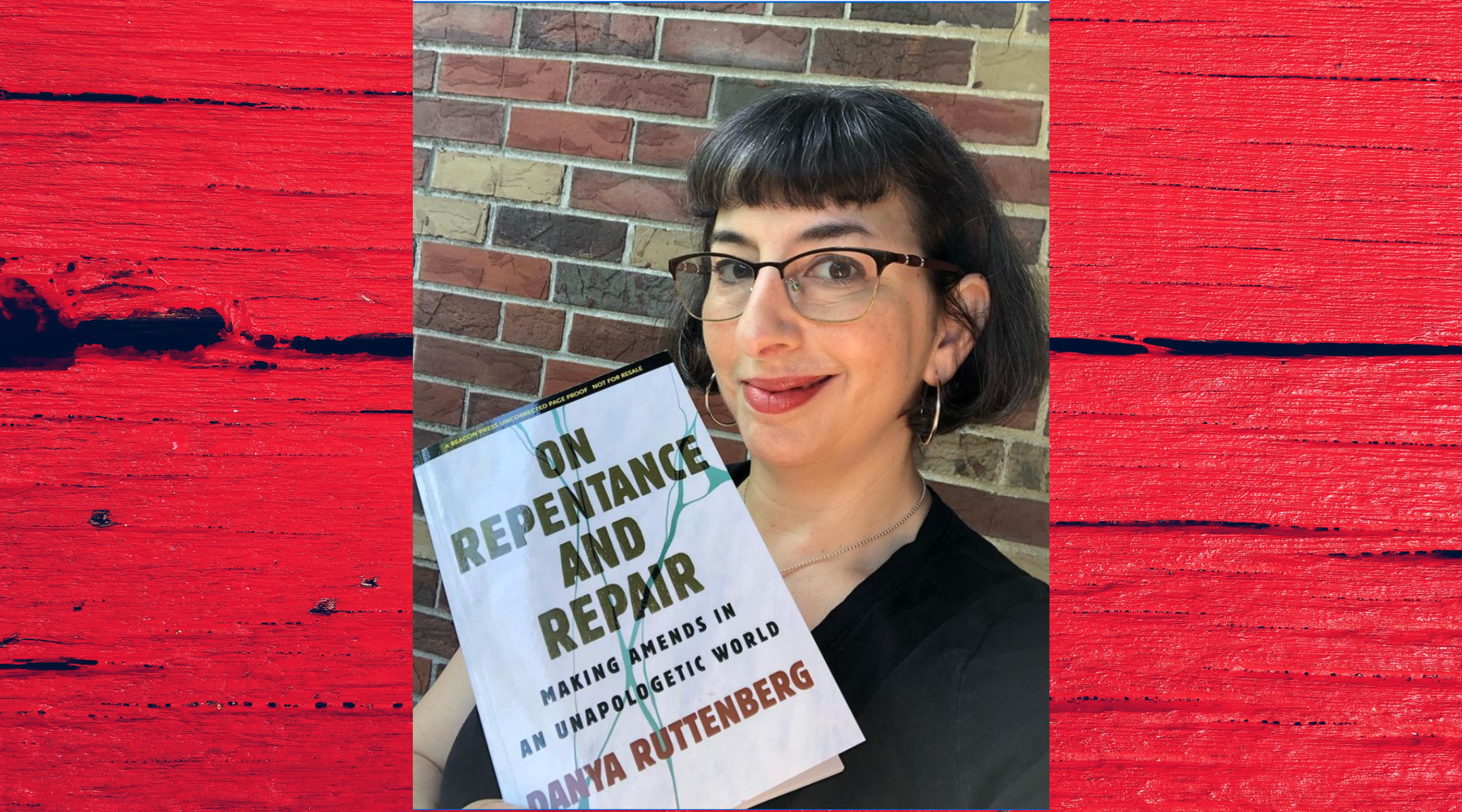

Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg holds her 2022 book about apologizing. (Instagram/Danya Ruttenberg)

Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg (@TheRaDR), scholar in residence at the National Council for Jewish Women

Twitter bio: “Rabbi & author.”

For me, the most profound impact of Twitter is how much I have learned from people who are not like me. Twitter is a place where people of many different backgrounds and perspectives and experiences can all exist in the same space and share their ideas, which makes it a wonderful place to teach Torah.

I love teaching Torah on Twitter partly because it is such a wild cross-section of people who have so many different responses and perspectives and questions that they bring as they engage with the topic at hand. Jewish conversations are richer as people who are not typically engaged in Jewish spaces are able to come and learn and sit at the table as equals, finally — people who have been marginalized for far too long in our community. And people who are not Jewish ask fascinating questions or make amazing observations based on their own expertise that illuminate the conversation. So the conversations are expanded and also have a depth and richness that I have not experienced anywhere else.

It reminds me very much of the story in the Talmud when Rabban Gamliel, the head of the Sanhedrin who was a bit of an elitist and problematic in other ways, winds up getting deposed. Rabbi Elazar ben Azaria is appointed to take over and he removes all of the gatekeeping and makes space for everybody and they add all of these benches into the beit midrash because people are pouring in to come and learn. People are desperate to learn and all they wanted was access and Twitter has been this access point for so many people, for so many Jews who have been marginalized in so many ways from our community, who have been desperate to be part of the conversation and to engage and have found deep community and learning and transformation.

We all are learning and growing as we make space for everything we can learn from people whose experiences are not like ours and try to get out of our echo chambers in a myriad of ways. And our Torah is deeper the more we are exposed to other ways of thinking and being and doing.

I do not know what is next. I have confidence that we will find our way to the next opportunity to learn and grow from each other.

But hopefully Twitter still has some life back in her. This platform is and has been something really extraordinary — the Arab Spring, #MeToo, Black Lives Matter: it has spawned profound movements — and I think a lot of us have learned and grown so much as a result of having access to it. I’m not going anywhere until the colonnades are falling around me.

Phil Keisman (@keismanphil), graduate student in European Jewish history

Twitter bio: “closing my twitter account at the end of the month”

The intersection of Jewish Twitter and academic Twitter I found to be a really invigorating community. As an example, a historian who was putting together a writing group of graduate students working on their dissertations was really into my tweets about basketball and German Jewish history and got in touch with me. Through that I met a close friend. Only social media can get through at the intersection of Judaism, basketball and academia.

Institutional Jewish life can tend toward the apolitical, especially when it has to do with Israel. I have found at times that there is not a place where I could be a progressive Jew and wear both hats. Jewish Twitter absolutely has been that space, which is both good and bad: It leads to bubbles, which are not good, but there’s this sort of leftist streak, this egalitarian-but-not-normatively-Orthodox sort of subgroup that I found very engaging.

And the jokes were fantastic. The first Jewish Twitter person I found was this person whose handle is ”Maimonides Nutz”! There’s this language of insiderness that typically happens in yeshivas and shuls, places that are typically male and typically white. All of a sudden we have this space with people with less learning, people with more learning, women, and Jews of color and people in the LGBT community —and suddenly there’s this outlet for Jewish humor that had funny possibilities and subversive possibilities. I’m going to miss that kind of cultural commentary and I’m going to have to hunt for it a little more.

Because I’m quitting. I don’t have any illusions that there are wonderful altruistic billionaires walking around, so it’s not anything about the previous regime, but Musk is such a bully. And I’ve also found myself having bad experiences. I’m involved in basketball, and you’ve got Kyrie Irving on the heels of Kanye, and all of a sudden my feed was filled with antisemitism. I realized I don’t have the control over my feed that I would like, and that Twitter is making me feel terrible. I’ve got a beautiful baby boy, I’ve got a dissertation in progress, I’ve got a wife, I’ve got lots of things that can demand my attention that aren’t this.

But if I find myself in a place where either things are so bad in the world that this decision no longer feels so salient or something changes in the ecosystem, I could totally see myself coming back.

Sophia Zohar (@MaimonidesNutz), artist, writer and internet personality

Twitter bio: “Maimonides, as in the 12th Century Jewish philosopher – and Nutz as in ‘Deez Nutz.’

I am saddened by the changes we are witnessing in Twitter’s leadership. Twitter has always been a place with the immeasurable power to bring people together, so it makes sense that some would seek to harness that power for their own gain. However it is that same power that has allowed JTwitter (or Jwitter) to come together and flourish during such a dark time.

We have played Talmud games together, we have made memes out of antisemitic tweets, we have even had conversations about the future of Judaism, and found how many similar things we hold dear. Jwitter has always been a forum for bringing together new and old forms of Judaism and I am honored to have been a part of that. I admit I have been weary at times (including now), but I plan to stick around because I am hopeful that not all of that has to change.

Alex Zeldin and Tamar Caplan are lifted on chairs during their wedding reception. (JC Lemon Photography)

Alex Zeldin (@jewishwonk), columnist and commentator on Jewish issues

Twitter bio: “All bad takes are mine alone.”

Twitter has had content moderation problems for years, which most Jews on the platform are well aware of because of years of harassment from Nazis and other antisemites. Musk’s purchase of the platform has not been encouraging from a content moderation perspective, considering the people championing it inside the company were swiftly fired.

I’m taking a wait-and-see approach on what it means for my use of the platform. I’m not ready to give it up just yet. I’ve made many good friends. I’ve learned a lot about all kinds of Jewish communities because of relationships forged on this platform. Every opportunity I’ve gotten to write and speak to Jewish audiences came from here too. My guess (hope?) is Musk will eventually learn the same lessons Twitter’s previous management did: nobody likes being constantly harassed by bigots. Beefing up content moderation is good for users, especially minorities like Jews and other marginalized groups, and ultimately good for business. If he doesn’t learn, I hope I can take my bad Jewish food takes to other platforms.

Elad Nehorai (@eladnehorai), writer and activist

Twitter bio: “Ex-hasidic, pro-good trouble”

Jwitter is — and God I hope it stays this way with the arrival of our new overlord — a beautiful, cantankerous microcosm of the Jewish people. It’s got the synagogue you don’t go to, which is maybe more important than the synagogue you do go to. The people who you trust and joke with, along with the group you are ashamed of, as well as the group that you know talks trash about you about your back.

Because we are so small, we know everyone (whether we like it or not). This creates a sense of intimacy and connection on a social media site that is in many ways defined by the chance that at any moment you could say the wrong thing and tens of thousands people you never heard of could tell you you’re the worst person to ever walk the earth. At least on Jwitter, when they tell me that I know them. It’s more like that frustrating uncle that you probably shouldn’t have invited to the family reunion than a mob. We can’t stand each other, but in the way that family can’t stand each other. It’s based on an awareness that underneath it all, we are united on this journey together. And maybe that’s part of what makes us cranky.

It’s also like a microcosm of the world itself, if I’m being honest. And I mean that in a depressing way. We are a small group on there, and the antisemites outnumber us. With moderation loosened or eliminated, they will probably continue to grow. In many ways, we get a front-row seat to the rise of these extremists, since at any moment they might attack us or target us. Amazingly, this has further united the Jwitter population: We have learned how to use our networks to push back and demand better. It is specifically because we are small, because we are family, because we have our culture of cliques and grudges and love and joy, because we all know each other, that we can fight back. That when people try to rewrite our story, one person will raise a flag and we’ll join in. We know the urgency of this moment, and we stand together even when we can’t stand each other.

This to me is the beauty of being Jewish as well, and it’s why I thank God for the messy beauty that is Jwitter. Every day, I get to spend time with queer Jews, activist Jews, Jews of color, anarchist Jews, Hasidic Jews, ex-Hasidic Jews, anti-fascist Jews, fascist Jews, punk Jews, artistic Jews, Jewish celebrities, Jewish lawyers, Zionist Jews, anti-Zionist Jews and so much more. Every single day, it’s like walking into the most diverse congregation on earth. People who, no matter how separated, are connected by their care for their people. By the fact that they simply show up. That they connect and have the tough discussions. This is what makes us strong. This is what makes me grateful.

Russel Neiss (@rmneiss), Jewish technologist

Twitter bio: “I (try to) write code to make the world a better place.”

The thing that I loved most about Twitter was the same thing that I loved about EJewishPhilanthropy before it was acquired by Jewish Insider two years ago — both places provided a platform for anyone, even a schnook like me in the middle of flyover country, to be a part of the broader conversation of ideas, and to challenge those who held real power so long as you were able to articulate yourself effectively.

Even in the best of times Twitter’s lack of decent moderation tools, inconsistent ground rules, and culture that rewarded being a jerk made it a sub-optimal place to hang out. At some point I coded up some scripts to automatically ban any problematic user who interacted with me based on some rough heuristics, that made my experience here much better. Last I checked there were nearly 100k accounts on that list. Those two things are almost certainly related.

I’ve been thinking quite a bit lately of Darius Kazemi’s 2019 essay on the benefits (and challenges) of hosting your own small social network [runyourown.social] — I’m not sure if I’m ready to fully make the commitment that that entails, but this week I did register san.hedr.in and I plan to install a Mastodon instance there this week. I don’t plan on letting it grow beyond 71 users though.

Dovid Bashevkin (@dbashideas), NCSY director of education

Twitter bio: “Rejected from many prestigious fellowships & awards”

I’m very proud of the Jewish community that has been built on Twitter. And I have no plans of leaving as far as I can tell.

Giving people a lens to celebrate their own experiences, their own culture, which I think Jewish Twitter has done a fairly admirable job of, is so beautiful, and I certainly hope it continues.

I’m also incredibly proud of this tradition, which some people hate and some people love, of sharing the books that you read over Shabbos. Every Saturday night, I post what I read. It takes social media out of the treadmill of opining on world events, and it provides an accessible entry point for people to engage with Shabbos in a meaningful way online. This, to me, goes beyond Twitter and is not something I would ever shut down.

I love that the Jewish Twitter world has adopted this meme of political world leaders, and captioning pictures of them in Jewish situations. When you see, like, a stern look of Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer, and you caption it “telling your Jewish in-laws that you’re going into Jewish education” — those types of moments allow a playful way to interpret world events through a niche Jewish lens. Some people may find it’s diminishing, or it’s not serious enough. But I think that that is very much in line with the Jewish tradition of humor, which has exploded on Jewish Twitter.

The way memes work is the more niche and specific the situation, the moral hyperlocal it is, the better the laugh, and the more people enjoy it. A lot of the things that have gone viral are drawing upon a very specialized Jewish knowledge. Twitter has taken Jewish culture online beyond bagels and lox, and really draws upon a very rich, specific Jewish experience.

There’s also a lot of cultural overlap and experiences that people have had in the Orthodox world and in other intensely religious communities, and sometimes you’ll see that in the memes or the moments or the idiosyncratic experiences that they share. I once saw an evangelical Christian account making fun of how at their youth retreats there’s always one guy who loves schlepping too many chairs, which is also a very Jewish shabbaton experience.

I wouldn’t call those moments religious education. But I think they’re celebrating religious experiences. And that, too, is holy.

Shayna Weiss (@shaynamalka), associate director of the Schusterman Center for Israel Studies at Brandeis University

Twitter bio: “Scholar of Jewish Studies. Lover of Israeli TV.”

I don’t have a lot of faith in Elon Musk, but I do think it’s too early to tell about Jewish Twitter. Social media platforms or the ways we communicate are always temporary. People talk about if you only read on a screen, it’s not real. Well, I have a friend who does ancient Judaism whose joke is, I don’t want to talk to you unless you’re only reading things on codexes.

It’s hard to know what my breaking point would be. I feel like it’s now sort of like a Jewish goodbye, when people say goodbye without actually leaving.

It was useful to me as an academic. I connected with amazing people that I don’t think I would have connected with otherwise, academics from different parts of the world or reporters or other people doing research. I have invited people to speak at Brandeis because they had posted about their scholarship on Twitter whom I’m not sure I would have heard otherwise, including a scholar in England.

And there’s lots of little niche communities on Twitter, like for OTD or “off-the-derech” [formerly Orthodox] Jews or voices from the haredi [Orthodox] community; reading what they said and what they thought was interesting to me and offered a window into a conversation space that I might have not had a window into otherwise.

But because Twitter didn’t engage in some of the moderations and structures that it should have, you have to use it in a very specific ways for it to be useful — and it still has issues. I had to be very liberal about using the block button, and I still got called Nazi more than once.

Abraham Josephine Riesman (@abraham joseph), journalist

Twitter bio: “Ladybearded authoress”

I can’t imagine that Twitter as a place where people like me feel comfortable is going to exist in like a week. I really think it’s going down in flames as we watch.

By the time I started wanting to yell about things in the Jewish world, Twitter was already sort of the place where that happened. I sort of melted into Jwitter around like 2018 or so. To be honest, I think it kind of ran its course. All the arguments that could be had on Twitter have kind of been had at this point. Even though I’ve only been on for a few years already, it just feels like there’s nothing new to say on Twitter anymore.

The food fights, the hamentashen-versus-latke fights that people would have, or whether we should cancel hamentashen or whatever, that kind of stuff was fun. But after a while it started to feel like, OK, but the world’s on fire. I know that Jewish humor is often about taking things like the world’s on fire, and saying let’s make a joke. But the best kinds of jokes are the ones that have a little bit of truth, edge and argument to them, and I feel like people are either afraid to make an edgy joke … or they’re just too wrapped up in having fights all the time.

The food fights were always proxy battles, or at least distractions from the real fights, which are about the things that can’t be easily resolved on Twitter. We’re not going to solve intermarriage, we’re not going to solve gay rabbis in Orthodoxy, we’re not going to solve Zionism and how Israel relates to the Palestinians on JTwitter. But that doesn’t stop people from arguing about them on there.

I won’t miss the fact that you have lots of people whose side is winning in the fights who are acting like they’re still the victims. That said, I am nostalgic for some things. I really did make a lot of friends. And I shouldn’t be ungrateful because, my god, I have gotten so much readership through Jewish Twitter. There were people supporting me there and finding what I had to say interesting, and I am eternally grateful for that. It was only a few years but being part of JTwitter really did alter the course of my career and therefore my life.

I don’t know where people are going to go. Maybe we’ll all go back to keeping up written correspondence where we discuss the great wisdom of the sages. I’d much rather that the place Jews come together be at the Shabbat table, rather than JTwitter. The better conversations come in smaller, direct settings rather than, you know, quote tweet-dunking on people. In fact, there are definitely Shabbat tables I got invited to because of Twitter. I really owe the people on there a great debt.

Caleb Guedes-Reed contributed reporting.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.