(New York Jewish Week) — Many Holocaust documentaries follow a familiar arc, from normalcy, to the unthinkable, to destruction. The last reel often includes scenes of corpses and skeletal survivors, usually in the company of the American and Russian soldiers who liberated them. The films might end with clips from the Nuremberg Trials, or vignettes of survivors setting out to start new lives.

A new film examines what happened next — specifically, the effort by Israelis and Diaspora Jews to seek justice, resettle survivors and rebuild their lives in the aftermath of mass murder. “Reckonings,” which had its premiere in New York last month, is being billed as the first-ever film on the reparations negotiated by Israel and Diaspora Jews with the newly formed West Germany.

Funded by the German government with support from the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (the Claims Conference), the film examines an unprecedented moral accounting by the perpetrators of genocide and the difficult decision by Israel and the survivors to accept what so many disdained as “blood money.”

“I remember growing up going to meetings of Holocaust survivors and listening to the debates and the arguments,” Abraham Foxman, the former head of the Anti-Defamation League and a child survivor of the Holocaust, said at a panel discussion following the film’s screening last month at The Paley Center for Media in New York. “I remember the arguments around the kitchen table at home. My father said no, my mother said yes. It took me a long time — to get to Germany, to begin to reconcile — and I think that’s the important message of the film.”

“Reckonings,” written and directed by Roberta Grossman, shows how those debates played out in conference rooms in West Germany, Israel, Europe and the United States. Konrad Adenauer, the staunch Catholic who led post-war West Germany, is seen in 1951 urging the Bundestag “to provide moral and material restitution” to Holocaust survivors. The film recounts the bitter debate in Israel over whether to accept money from the Germans, with Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion reluctantly but firmly in favor, and right-wing Knesset backbencher Menachem Begin passionately opposed.

Ben-Gurion won out, arguing that Germany should not be to keep the property stolen from the Jews it murdered, nor escape accountability for its crimes. When Israeli and German representatives began their face-to-face talks in March 1952, it was understood that the reparations were not meant to put a “value” on the lives lost, but would be regarded as material compensation for property stolen and livelihoods cut short.

Israel, barely solvent, also had practical needs, and sought funds for resettling hundreds of thousands of survivors.

A third partner in these negotiations was a consortium formed by 23 Diaspora Jewish organizations at a meeting in New York City in October 1951. The Claims Conference would negotiate on behalf of Jewish survivors living outside of Israel.

The film uses archival footage and reenactments to dramatize the bureaucratic wrangling that led, on Sept. 10, 1952, to the signing of the Luxembourg Agreement codifying West Germany’s obligations to Israel and the Diaspora. Holocaust survivors describe their unspeakable losses, and their own struggles to accept reparations. Historians describe the tension in the meeting rooms, where Israelis refused to speak German or shake hands with their German counterparts.

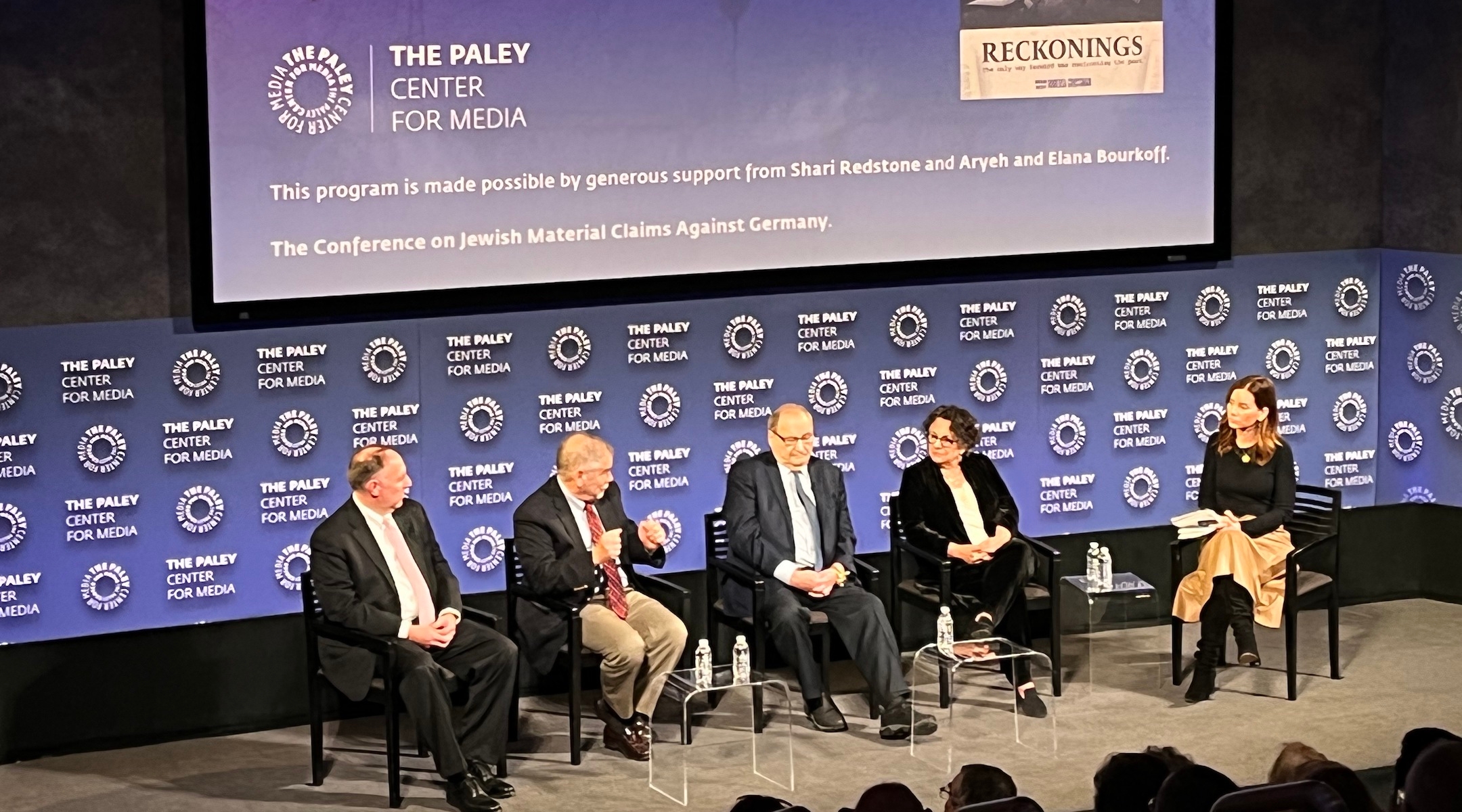

Panelists following the premier of “Reckonings” at The Paley Center for Media in Manhattan included Gregory Schneider of the Claims Conference, Holocaust historian Michael Berenbaum, former Anti-Defamation League head and Holocaust survivor Abraham Foxman, filmmaker Roberta Grossman and panel moderator Rebecca Jarvis of ABC News, Oct. 27, 2022. (New York Jewish Week)

Ben Ferencz, the New Yorker who, at 103, is the last surviving prosecutor of the Nuremberg Trials, talks about attending the founding meeting of the Claims Conference and participating in the negotiations that led to the Luxembourg pact.

Seventy years after the historic agreement, Gregory Schneider, executive vice president of the Claims Conference since 2009, described the atmosphere in the rooms where representatives of Germany, Israel and the conference still meet to hammer out further agreements.

“There are times when there’s fists pounding, there are times when there are tears, maybe on both sides,” Schneider said during the panel discussion that followed the screening. He cited Saul Kagan, the founding director of the Claims Conference, who is quoted in the film saying that the “souls of the six million” who were murdered were in the rooms with them when they negotiated reparations.

Since the initial agreement, the German government has paid more than $90 billion in indemnification. In September, Germany agreed to one of its largest financial reparations packages ever: some $1.2 billion to help cover health care costs for aged survivors. This year, the Claims Conference will distribute over $700 million to more than 210,000 survivors in 83 countries, and $720 million in grants to social service agencies that provide home care and other vital services for survivors.

Panelist Michael Berenbaum, one of the historians of the Holocaust who consulted with the filmmakers, said reparations are not just about property but dignity — restored to survivors “throughout the world by those who refused them the most elemental dignity when they were young.”

“This is a tremendous historical act of atonement,” Berenbaum said. “And it’s also an act of enormous grace.”

“Reckonings” is being shown at Jewish film festivals throughout the country. It will be shown at the Marlene Myerson JCC Manhattan on Nov. 21 and at Manhattan’s Leo Baeck Institute on Dec. 5.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.