(New York Jewish Week) — A New York revival of the 1998 Broadway musical “Parade” — about the 1915 lynching of a Jewish man, Leo Frank, at the hands of a Southern mob — arrives at an auspicious, if not ominous, time. Antisemitism is again part of the national conversation, while nationalism and accusations of racism form the backdrop to next week’s midterm elections.

As the star of the revival, Ben Platt, told The New York Times: “This show is all about not only antisemitism, but the failure of the country to protect lots of marginalized groups, and we’re all feeling that really intensely right now.”

Of course, a musical about national trauma is not everyone’s cup of sweet tea, and despite its Tony-winning book and score, “Parade” has always been dogged by criticism that it is too relentlessly downbeat to pull in the crowds.

Not this new, stream-lined production, part of New York City Center’s limited-run series of “Encores!” revivals. (The last performance is Nov. 6.) Thanks to Platt and a huge, excellent cast that includes Gaten Matarazzo (Dustin from the Netflix series “Stranger Things”), the show manages to be stirring and, yes, entertaining, without losing sight of the tragedy at the core.

The Leo Frank story is America’s Dreyfus Affair. Frank was a Jewish, Brooklyn-born college graduate who managed a pencil factory in Atlanta, Georgia owned by a relative. In 1913 the body of a 13-year-old factory worker, Mary Phagan, was found in the factory’s cellar, and the police fingered Frank in the rape and murder. After a trial marked by flimsy evidence and implausible “eyewitness” testimony, Frank was found guilty and sentenced to death in 1915. A rabid local press demonized the Jewish outsider, leading progessive politicians and newspapers from outside the South to demand that Georgia Gov. John M. Slaton commute Frank’s sentence and reopen the case.

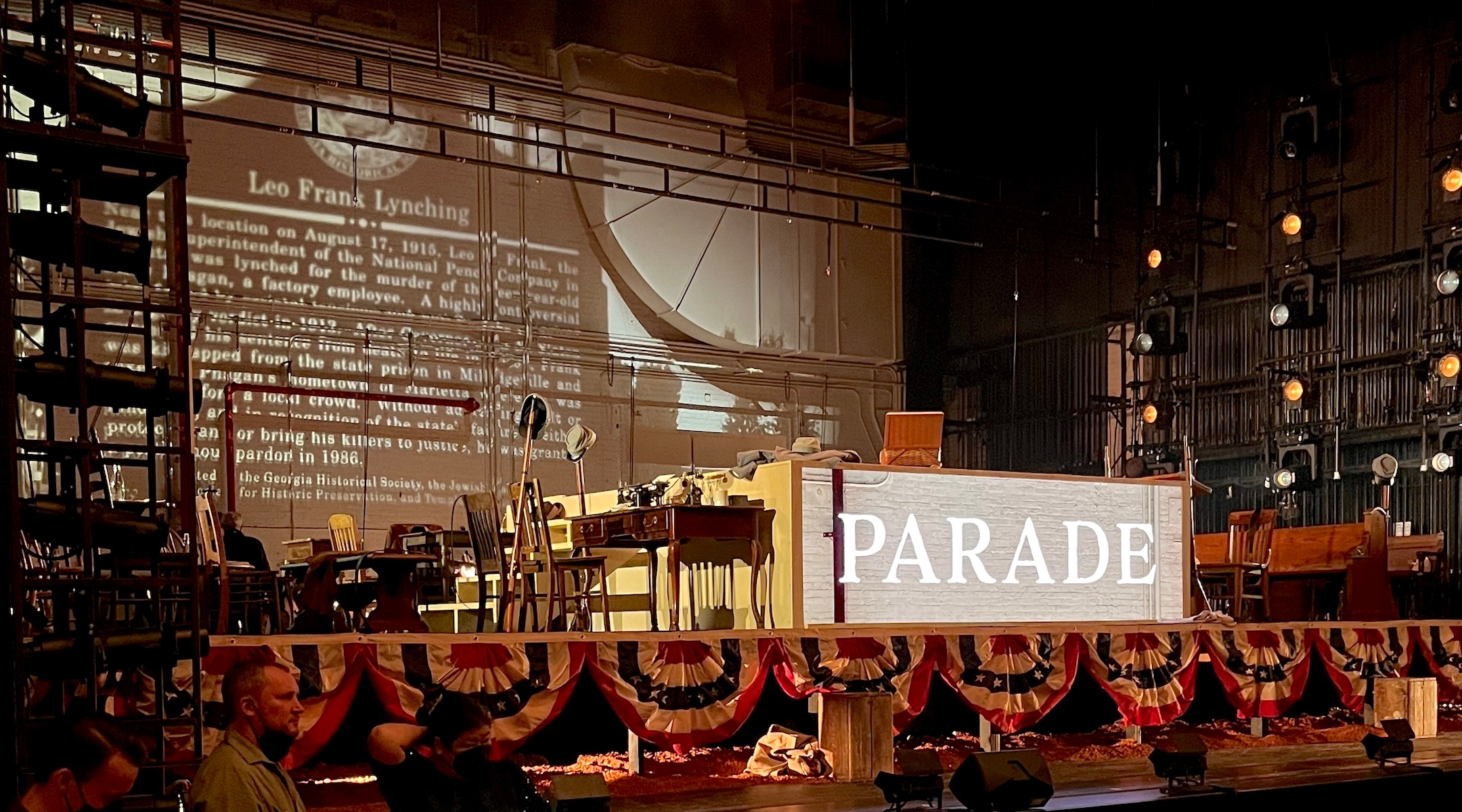

The revival of “Parade” at New York City Center uses rear-wall projections to bring in the historical reality of the events being performed on stage. (New York Jewish Week)

Slaton relented, but on Aug. 16, 1915, an armed mob snatched Frank from prison and lynched him in Marietta, Georgia. The case famously inspired a revival of the Ku Klux Klan — and led to the founding of the Anti-Defamation League, today’s powerful Jewish defense and civil rights group.

“Parade,” with a book by Alfred Uhry (“Driving Miss Daisy”) and music and lyrics by Jason Robert Brown, leans hard into the hysteria surrounding the Frank case. The various townspeople form a Greek chorus demanding “justice.” There are characters representing the racist, sensationalist press; there is a politically ambitious prosecutor, a cynical judge and, in the case of Slaton’s character, a genteel Southern governor caught between an angry public and his own instinct to do the right thing.

The musical centers what begins as a strained relationship between Frank and his wife Lucille, a Jewish Atlanta native. There are laughs early in the show when Platt talks and sings about the differences between the Jews he grew up with and the Southern variety. Their marriage is portrayed as a cold, sterile affair, with Frank too concerned with things at the factory to notice the loving, generous Lucille. The warming of their relationship — culminating in a jailhouse duet, “All the Wasted Time” — forms the emotional arc of the show.

This could come off as schmaltzy, but the City Center production stays grounded in historical reality. Contemporary newspaper clippings and images of the real-life historical figures being portrayed are projected on the rear wall of the stage in lieu of conventional scenery. (“Encores!” productions are only partially staged.) Platt — small and vulnerable, with a catch in his singing voice — humanizes Frank. I object to the idea that only Jews should play Jewish characters, but I concede that Platt’s background — he is famously Jewish in a Camp Ramah, his-mother-is-a-leading-Jewish-philanthropist kind of way — adds a level of resonance to his performance.

The show is a helpful reminder about the potent force antisemitism was in America until it was driven largely to the fringes after World War II. The Frank case is a historical rebuke to those who cannot imagine Jews as a “minority” or persecuted class. It helps explain why groups like the ADL remain so adamant in exposing and combating antisemitism in its present-day forms: die-hard conspiracy theories, political dog whistles, online harassment, street attacks on Orthodox Jews — and, yes, spasms of deadly violence.

And yet “Parade” is careful not to take this refutation of “white privilege” too far. Act II begins with a duet sung by the Black domestic workers at the governor’s mansion. Anticipating the hordes of Northern reporters coming to cover the Frank trial, they sing bitterly, “The local hotels wouldn’t be so packed/If a little Black girl had gotten attacked.” Nor, they sing, would the press have cared if the wrongly accused defendant was Black. Their song is a necessary corrective in a musical about the post-Reconstruction South that focuses on the lynching of a white man.

The audience for Tuesday night’s premier was ecstatic, and the wild applause for the performers was well-deserved. Brown led the orchestra, and invited Uhry, now 85, to join him and the cast during the curtain calls.

Still, there is something strange about cheering a musical that begins and ends with a pulse-quickening, pro-Confederate anthem called “The Old Red Hills of Home.” The song is clearly meant to be ironic, and its power effectively implicates the listener in the kind of nationalist fervor that so often goes so terribly wrong. The question that lingered is whether we were being invited to look down on backwards Southerners of yore, or recognize the ugly nativist trends that still animate American politics.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.