(New York Jewish Week) — In his best seller “The Hare with Amber Eyes,” Edmund de Waal traces the rise and fall of his rich and influential Ukrainian, French and Viennese Jewish family from the late 19th century to the 21st. Its organizing principle is a collection of tiny Japanese carvings, or netsuke, that accompanied the family through nearly every stage of their journey.

The objects are the skeleton keys that unlock the family story. In writing the memoir (which became a terrific exhibit at New York’s Jewish Museum last year), de Waal explained that he wanted “to walk into each room where this object has lived, to feel the volume of the space, to know what pictures were on the walls, how the light fell from the windows.”

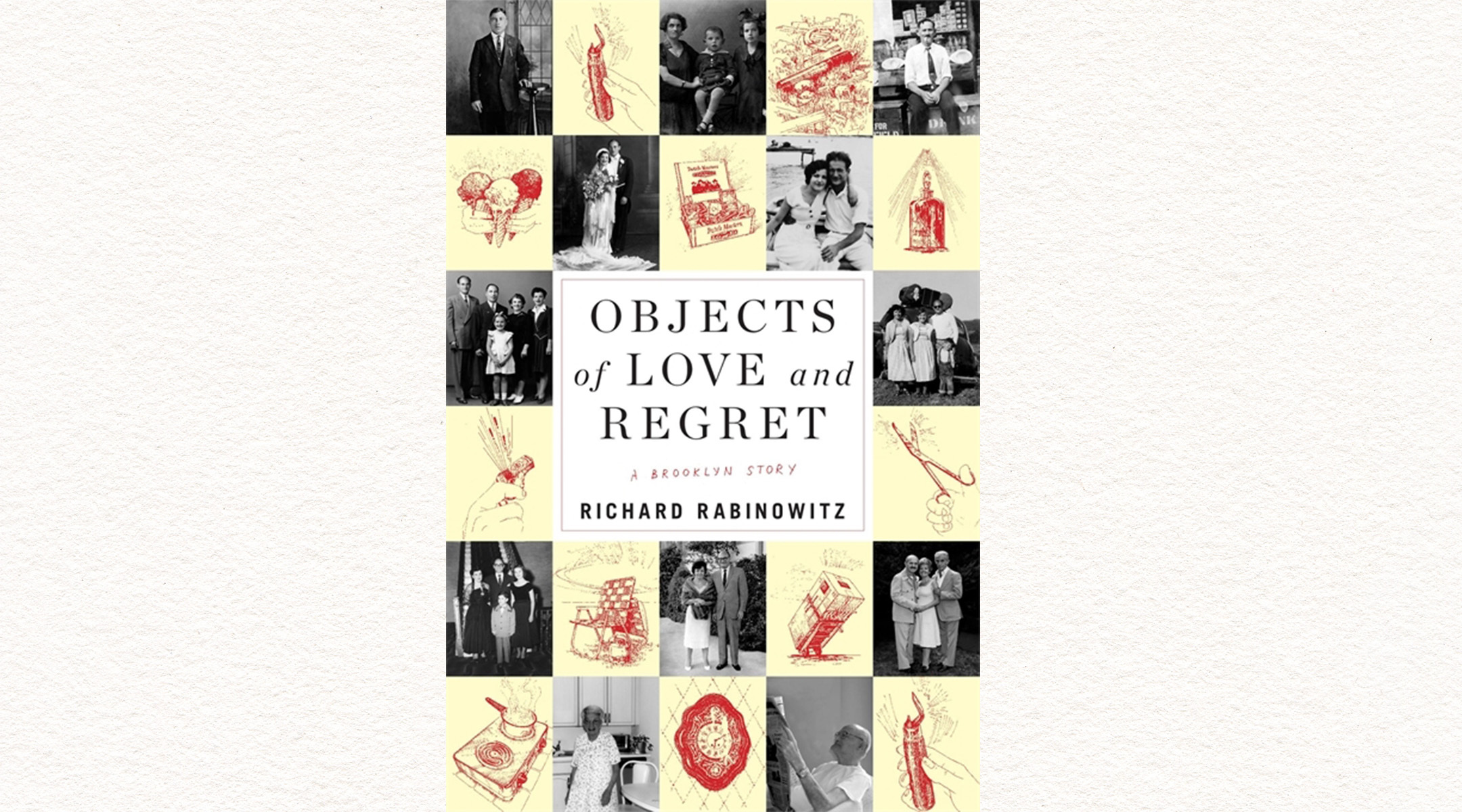

I thought of de Waal when reading Richard Rabinowitz’s lovely new book, “Objects of Love and Regret: A Brooklyn Story.” Like de Waal, Rabinowitz uses family objects to tell his family story; unlike de Waal, he is inspired by objects that are not heirlooms but common tchotchkes, and the family is hardly a storied dynasty.

David and Sarah Rabinowitz are lower middle-class Jews whose families arrived in New York in the early part of the 20th century — his dad’s family in 1905, his mother’s 20 years later. Through a series of homely objects — a bottle opener, a hot plate, a cigar box — Rabinowitz (with the invaluable help of his older sister Beverly) recreates his parents’ life and the places where they lived, including a very Jewish East New York, the high-rise near Rockaway Beach where they moved after the racial and economic upheavals transformed Brooklyn in the 1950s and ‘60s, and finally the Florida condo where they found some peace of mind after years of economic anxiety.

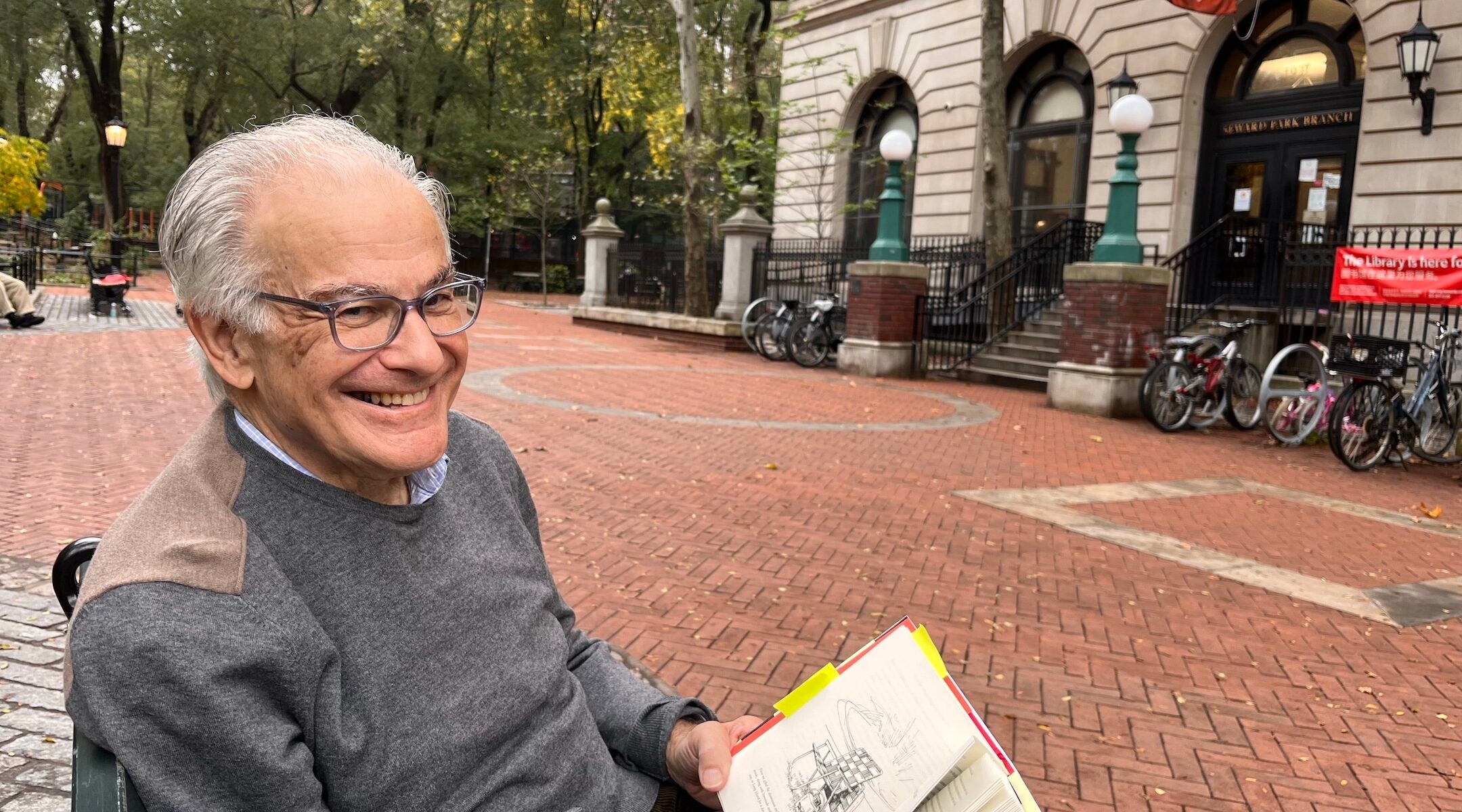

“I’m interested in the objects of everyday life because they help me understand the actions in the family, the relationships of people in the family,” Rabinowitz told me last week. A historian by training and museum curator, Rabinowitz was part of teams that created the Tenement Museum and transformed the Eldridge Street Synagogue into the Museum at Eldridge Street, both on the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

“There is a kind of tremendous richness in ordinary people’s lives,” he added. “That’s my animating principle.”

Rabninowitz and I spoke on a bench in front of the Seward Park Library on the Lower East Side, across the street from the Educational Alliance — founded to acculturate Eastern European Jewish immigrants — and the old Forward building, once home to the country’s most widely read Yiddish daily. His father David grew up nearby at 39 Essex St. In researching the book, Rabinowitz would walk the streets to discover the “tactility,” as he calls it, of his father’s childhood.

Although his son would attend Harvard University, David Rabinowitz struggled for much of his life: scraping together pennies selling newspapers as a boy; watching a jewelry business thrive and then fail; eventually supplying grocers throughout the city and Long Island until big operators moved in and forced him out of his one-man business.

“More than half of the Jews in New York City in the metropolitan area in 1950 were actually lower middle class,” said Rabinowitz, who was born in 1945. “I constantly meet people who have this experience of a lower middle-class life, but really nobody’s talked about that” — or at least, not in the best-known narratives of 20th-century Jewish life.

His stay-at-home mother, meanwhile, grounded the family in a Jewish ethos from which, he writes, “everything flowed.” His parents didn’t attend synagogue or observe Shabbat in a traditional way, but Sarah’s was a home-based religion in which the family ate kosher and she lit Sabbath candles on her own schedule, late on a Friday night. “Even when the teachings of the holy Jewish books failed Sarah, when the Ethics of the Fathers seemed too remote, when nothing quite fit correctly, she was nevertheless deeply loyal and attached to ‘her people,’” writes Rabinowitz. The family had almost no non-Jewish friends.

The antique bottle opener that helps Richard Rabinowitz tell his family story in “Objects of Love and Regret: A Brooklyn Story.” (New York Jewish Week)

“I want to argue, without making any explicit argument against anybody, that we don’t pay enough attention to actually how people practice being Jews,” he told me. “They lived in an insular world, very anxious, cautious about approaching [gentiles] even though antisemitism was diminishing through the course of their lives and they lived in such strongly, predominantly Jewish places.”

That insular world was blown apart in the 1960s, when, he writes, “the federal and city governments adopted policies and practices that effectively sorted and segregated New York’s working class, lower middle-class, and middle-class populations by race.” In 1960, 85% of East New York’s 100,000 residents were white. Six years later, 80% were Black or Puerto Rican.

Rabinowitz describes in detail — citing Walter Thabit, Craig Steven Wilder and other historians — how political and business interests hastened blockbusting, white flight and de facto segregation. The villains include a “crafty mortgage broker” named Harry Bernstein, who would eventually be convicted in a conspiracy to misuse federal funds designed to help the poor buy houses.

“My parents were 50, in the prime of life. The kids are growing up and suddenly everything comes apart and they lose this sense of safety,” said Rabinowitz. David and Sarah, he writes, never wholly recovered from the exile from their tight-knit Jewish neighborhood.

I told Rabinowitz that his book reminds me of Arthur Miller’s “The Death of a Salesman,” another product of a lower middle-class Jewish childhood. Like Linda Loman in Miller’s play, “Objects of Love and Regret” demands that “attention must be paid” to the “small” lives of ordinary people.

“I think that’s right,” said Rabinowitz, who recently attended the Broadway revival of the play starring Wendell Pierce and Sharon D Clarke. “That scene was just hard for me.” He also sees the play as an indictment of the “cruelty” inflicted on immigrants and the dispossessed by politics and economics.

“This country is all built around constant waves and waves of immigrants,” he said, gesturing to the Asian and Hispanic families going in and out of the library and enjoying Seward Park. “I think the Trump years have torn apart this kind of shield that the core of America was this promise of equal rights. In fact, there’s also this other, persistent violence” against the have nots. “This is a predatory society.”

“Objects of Love and Regret” uses ordinary household items to tell the story of author Richard Rabinowitz’s immigrant Jewish family. (Harvard University Press)

And yet, he writes, “I grew up in the luckiest of historical moments.” His parents and their neighbors had “crossed into the world outside the immigrant ghetto to start or buy a small business, or to get a job in the post office, the school system, or some other part of city government.” Richard attended the elite Stuyvesant High School before heading off to Harvard and a career his father could not have imagined. Despite his parents’ struggles, he said, “They caught the 1950s and the chance to take part in this expansion of American economic development.”

Which brought us back to the bottle opener, a green-handled device that his mother picked up for 20 cents in 1934 and presented as a gift to her mother — and which would bring her to tears in later years. Rabinowitz researched the history of the opener and manufacturer to tell a very different kind of immigrant story, but ultimately the device is about relationships — between family members, and between the family and the wider world.

His mother didn’t have the money to buy new appliances, but she could buy a bottle opener that would enable her own mother to open the kinds of consumer goods that would make them feel more “American.” And the gift also represented, Rabinowitz imagines, what mother and daughter shared: “the pleasures of caring for the kitchen, the home, and the family.”

At one point in our conversation, Rabinowitz reached into a satchel and brought out the carefully wrapped bottle opener. Infinitely less valuable than a Japanese netsuke, it looked about as rich as an object could get.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.