(New York Jewish Week) – On a recent sunny Thursday in the Rockaway Peninsula of Queens, a quiet breeze and ocean waves served as a gentle soundtrack for people walking their dogs on the beach or biking on the boardwalk.

The serenity of that temperate morning was a far cry from a decade ago, when Hurricane Sandy — also known as Superstorm Sandy — made landfall in New York City on Oct. 29, 2012, leaving many homes in the Rockaways flooded and destroyed, forcing hundreds of terrified people to evacuate.

Though Sandy may be a vague memory in many New Yorkers’ minds, for the citizens of the Rockaways, the trauma often feels fresh. “There are moments where you forget that it happened and there are moments that you just have to work your way through it,” said West End Temple’s Rabbi Marjorie Slome, who led the Reform synagogue in Neponsit through the worst of aftereffects of the storm.

In New York City, Hurricane Sandy left several neighborhoods across the city without power for days, killed more than 40 people and caused billions of dollars in damage. The Rockaways — a popular beach destination for New Yorkers and the subject of the Ramones classic song “Rockaway Beach” — was among the neighborhoods hardest hit by the storm. More than 1,000 homes on the slim peninsula were damaged or destroyed by the 10 feet of ocean surge.

“It was truly traumatic to walk into the building and see the water going up the stairs from the newly renovated bathrooms,” Slome said about the days immediately after the storm. “If you walked into the sanctuary, to see how forceful the water was — it uprooted pews. It was just devastating to see prayer books covered with salt water and waste. It was equally unbelievable that nature could be so forceful.”

Pews in the sanctuary of West End Temple were uprooted and strewn about after the storm. (Courtesy West End Temple)

Equally surprising, perhaps, is that a decade after this “once in a generation” storm hit, relief money remains unspent and storm resiliency projects remain incomplete. As Gothamist reported earlier this month, the federal government ponied up $15 billion for the estimated $19 billion in damages in New York City — but the city has spent just 73% of that money.

At West End Temple, which served about 100 families at the time of the storm, the synagogue also functioned as a community center for all in the neighborhood, with a gym and a nursery school. (There is also a sizable Orthodox community on the peninsula, with an estimated 10,000 members.) And while the synagogue is mostly rebuilt today — and in some cases updated — its lay leaders are still grappling with the bureaucracy, including tracking down promised financial assistance from FEMA for completed mold mitigation and cleaning issues.

“Ten years later, we’re still trying to track down the money,” said Lori Musumeci, the synagogue’s vice president and a lifelong resident of the Rockaway neighborhood of Belle Harbor. “At the time, we were in a traumatic state, and the government is asking us to find contracts and documents proving our claim from a decade ago.”

Most prayerbooks were destroyed in the storm, Slome said. The Central Conference of American Rabbis helped donate new ones. (Courtesy Marjorie Slome)

Still, for Slome, who retired in the summer of 2020 after a 35-year rabbinic career, what sticks with her the most from the storm was the generosity that came from every direction. For example, the Central Conference of American Rabbis, an umbrella organization for the Reform movement, donated prayer books and helped raise $750,000 for the congregation, which was underinsured against hurricanes, to rebuild.

“If it weren’t for all the people who came and volunteered from all over, I never could have done it. Like Mr. Rogers says, ‘Look to the helpers,’” Slome said. “It was horrible, but that was really the best thing. All the synagogues couldn’t have been more helpful in the New York City area.”

Volunteers worked tirelessly to put the congregation back together. Eventually, building doors reopened after a long winter. The sanctuary took more than a year to be rebuilt. (Courtesy West End Temple)

Musumeci concurs. “We made lemonade out of lemons,” she said.

In the immediate aftermath of the storm, Slome — who lives in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park South, and was therefore inland and safe from the worst aspects of the storm — sprang into action. She divided up the temple’s membership roster, and with a team of volunteers, made house checks — in one case, she found a congregant in her 80s fast asleep on the top floor of her house, waiting for the power to come back on, which it didn’t for months.

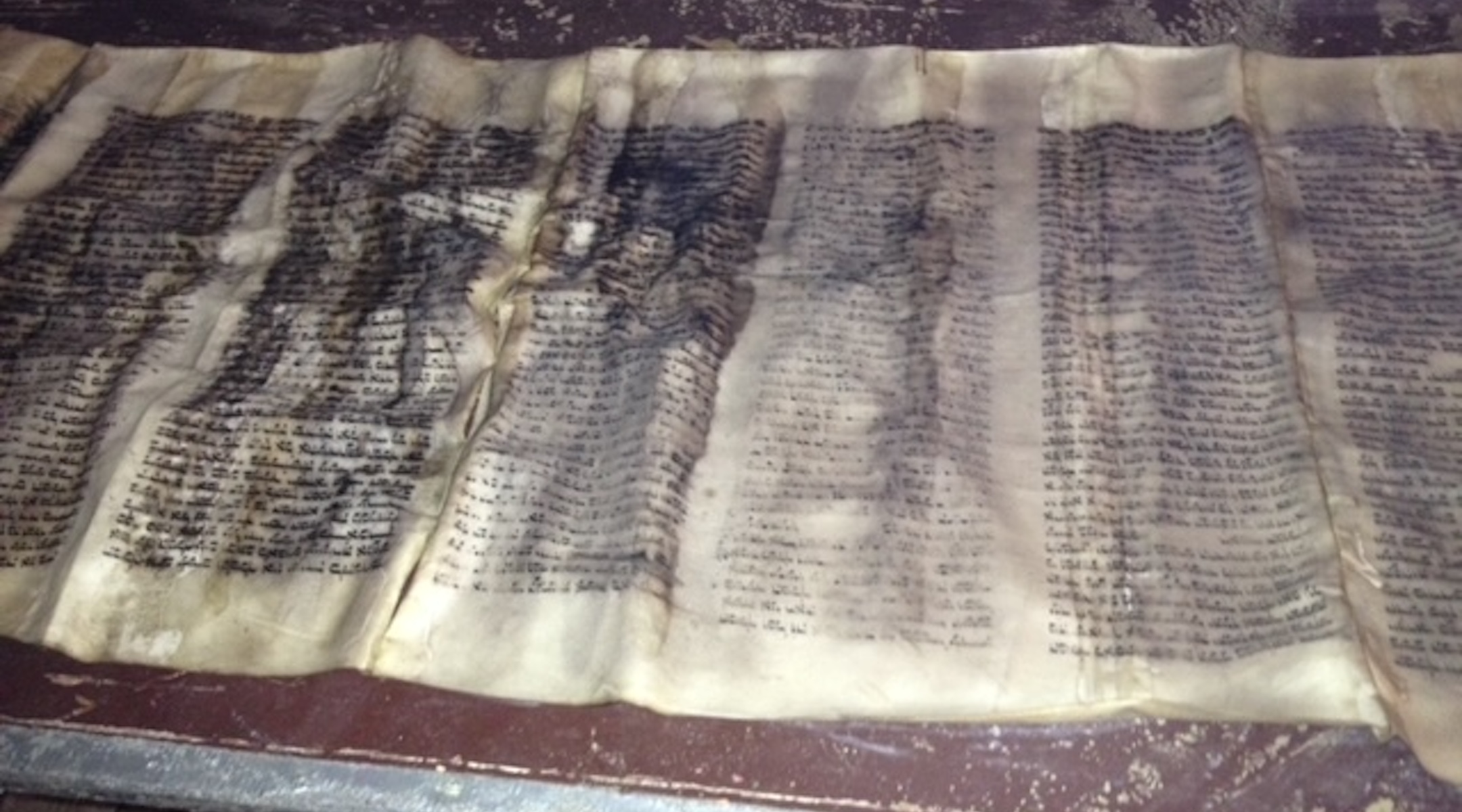

She helped some members coordinate places to temporarily relocate, kept the Torahs safe in her house — she knew enough to take them home before the storm hit — and dealt with finding contractors and collecting FEMA assistance to rebuild.

The synagogue suffered severe damage, although most of the Torah scrolls were kept safe at Rabbi Marjorie Slome’s house. “So much was lost,” Epstein said. Leadership is still recovering and realizing the depth of the loss. (Courtesy West End Temple)

Services were conducted and Slome met congregants in a temporary trailer throughout that first winter; the synagogue’s social hall was rebuilt by the beginning of the summer in 2013. Religious school and nursery school took place in trailers and then the social hall as well. It was more than a year until the sanctuary opened again.

Despite the destruction, the storm did provide opportunity for regrowth — both in a community sense and in a physical sense, Musumeci said. There are now better constructed stone jetties to protect the coastline and limit erosion; the boardwalk has been updated and revitalized and new luxury hotels have taken root.

On the coastline, a six-mile long storm surge protection project began in 2020, with newly reinforced dunes lining the beach and more sand brought in — the project, which is set to be completed in 2026, is using more than $330 million of federal funding.

“The Rockaways are a hundred times better than they were before the storm,” Musumeci said, “but the trauma has stayed with us.”

Construction on Rockaway Beach to better prepare the peninsula against storm surge is projected to last through 2026. (Julia Gergely)

Though membership at West End Temple is slightly lower than it was pre-Sandy, Musumeci said congregants are especially committed because the synagogue helped provide a sense of place in a time when all felt lost. “When I look at the temple and enter the building, I am so proud of the progress we made,” she told the New York Jewish Week. “We have reenergized and become stronger together.”

These days, West End Temple is helmed by Rabbi Rebecca Epstein, who came to the Rockaways from Park Slope’s Congregation Beth Elohim in 2021. The preschool, one of the congregation’s most popular offerings, is up and running stronger than before, as is the program for the community to rent out the gym space and social hall.

“The trauma is still with people,” Epstein said. “People put their blood, sweat and tears into making the congregation a sustainable place again.”

Taking over leadership in a community so impacted by the storm was not something Epstein took lightly. “I’m so moved and inspired by the resilience of the people that went through this,” Epstein said.

Possibly by some divine coincidence, the Torah portion that will be read this Shabbat on Oct. 29 — exactly 10 years after the storm made landfall — is Parashat Noach, the story of Noah’s ark and the flood that wiped out almost the entire world.

“There’s a direct connection between the Torah and this neighborhood — this is a real thing that happened in their lives,” Epstein said. “But in the ark, there was a window to look out into the outside world and to have faith in the future. There is always a message of hope that we can take with us.”

Still, Epstein is bracing for the day that a storm might come again. “I think about it all the time,” she said. “How can you not?”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.