VINNYTSIA, Ukraine (JTA) – Under a haze of early morning cigarette smoke, two Jewish men from Ukrainian cities in areas occupied by Russia were discussing how much they miss their parents. Neither had seen them for months and in the brief exchanges that they have had with them, they could only say so much without fear of putting them in danger.

“We can’t talk about the war,” says Moshe, who is from Kherson, a city in southern Ukraine that has been occupied by Russian troops since early in the war. “I don’t want to make things difficult for her. I think that people are listening in.”

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February, Jewish families in southern and eastern Ukraine faced a difficult choice: flee and become refugees or stay put and protect their homes. Many broke up, as elderly parents refused to or could not leave their hometowns, while their children left with the retreating Ukrainians or took steps to escape the Russian occupation and find themselves back in Ukraine.

“She doesn’t want to leave. It is not because the Russians are there now that she wants to stay,” Moshe says, clearly nervous about giving away too much information to a stranger. “She wants to stay because it is her home.”

Moshe had come to Vinnytsia, a town in western Ukraine, for work two weeks before the invasion. Beside him was Igor from Berdyansk, a town on the Sea of Azov, who smuggled himself across Ukrainian lines after the Russians occupied the city. His decision to leave came after friends were arrested on suspicion of being pro-Ukrainian partisans.

“They occupied the city on March 5,” he says. “I was able to break out in April. They completely shut down the city for a week after they entered the city looking for soldiers and partisans. They were sending people to prison, or rather, that was the good way.”

He, too, left his parents behind. “I speak to them when I can,” he said. “There is not always signal.”

Russia illegally annexed four occupied Ukrainian regions in late September after staged referendums. The Jewish Telegraphic Agency spoke to Jews from all four regions that still had contact with relatives back home. Nobody who spoke to JTA that still had family in Russian-held areas was willing to give their full name for fear of possible consequences.

A woman casts a “yes” vote on whether her area should become part of Russia, part of controversial referendums staged by Russian occupying forces in four regions of Ukraine, Sept. 27, 2022. (Stringer/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

In territories that had been occupied by Russia but have been reclaimed by the Ukrainians, government and human rights watchdogs have found evidence that people suspected of Ukrainian sympathies were tortured and murdered.

It is not known how many Jews are currently living in areas under Russian occupation, although it is believed that a large number have left since the Feb. 24 invasion. Many evacuated through humanitarian corridors to Ukrainian-held territory, while others have left through Russia and either made the long trip through the Baltic states, Poland, and back to Ukraine, or gone onto Israel. “You need money to do this,” noted one man.

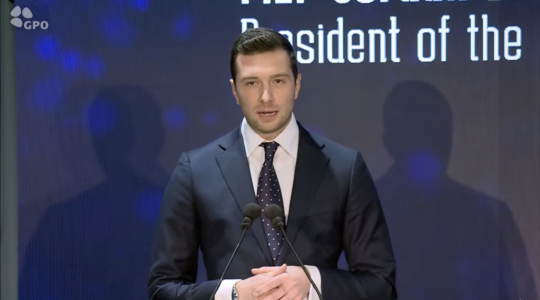

Israel’s ambassador to Ukraine, Michael Brodsky, told JTA that Israel did not “directly” have contact with Jewish communities in areas that Russia controls. “We do not deal with the occupied territories at all,” he said.

Ambassador of the State of Israel to Ukraine Michael Brodsky speaks to the press in Dnipro, Ukraine, in November 2021. (Mykola Miakshykov/ Ukrinform/Future Publishing via Getty Images)

When asked what support Israel could provide to Jews in occupied areas of Ukraine, he stated: “We do sometimes get requests for humanitarian involvement and we assist on a humanitarian basis, but this is not a general policy.”

“We sometimes get requests from Israeli citizens that their relatives are somewhere in the occupied territories,” he added. “We can make an inquiry. We can also speak via our embassy in Moscow with the Russians about it, as long as it is a humanitarian issue. It is fine.”

The Ukrainian government also told JTA that it did not have direct contact with Jewish communities in occupied areas of Ukraine, explaining that it was dangerous for many to maintain a line of contact with the Ukrainian government. The only rabbi known to remain in Russian-occupied areas, in Kherson, did not reply to a request for comment.

That rabbi, Chabad-Lubavitch-affiliated Yosef Yitzchak Wolff, recently described a grim situation to Chabad.org, the news service of the Hasidic movement. “Nothing has changed in half a year. There’s been no improvement,” he said just before Rosh Hashanah, adding, “We’re still in a war, but we’re making sure everyone is able to have a happy, sweet new year.”

Since Igor left Berdyansk, the messages that he has been getting from his parents paint a picture of a Russian occupation that has become more paranoid and oppressive. “If you are standing around smoking, they come up to you to check your documents and question you. They ask you what you are doing there and why you are hanging around.”

“It is banditism. There is no society,” he explains. “They come and ask you for money and if you do not cooperate, they take your children and demand a ransom.”

Boys sit in front of a damaged building in Mariupol, Ukraine, Sept. 26, 2022. (Stringer/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

A recent investigation by the Associated Press found that Russia has taken thousands of Ukrainian children to Russia for adoption and propaganda and given them Russian passports. Many were taken without consent and told that their parents had rejected them, according to the AP report.

Among all the Jews that the JTA interviewed who had left areas occupied by Russia, there was pessimism that any serious Jewish life could be sustained. “There are maybe around 100 Jews left in Berdyansk,” said Igor. “But they are only old people — all the young ones have left.”

He did not believe that being Jewish in areas now occupied by Russia made any difference. “Nationality doesn’t matter for the Russians. For them, these people are not people, they are animals.”

While Berdyansk was too small to have a full-time rabbi before the war, Mariupol, a city further along the Sea of Azov, did have one. Mariupol has become a symbol of Ukrainian resistance after Ukrainian soldiers held out for almost three months, in a battle that destroyed much of the city.

A Jewish man puts on tefillin, prayer phylacteries, before praying in a bomb shelter in Mariupol, Ukraine, during the first week of Russia’s war on Ukraine. The city has been heavily damaged and officials warn of a potential catastrophe there if humanitarian aid is not permitted. (Photos provided to JTA)

There is still financial and other support from outside Ukraine that is being provided to Jewish communities in areas under Russian occupation, but few are willing to talk openly about it. It is a crime under Ukrainian law to send money to areas under occupation and there is concern that if the methods used to support Jews in these cities becomes public, fragile networks and people could be put at risk.

“There are a few old people from the community that refused to leave in Mariupol,” said Olga, a teacher who was closely involved with the Jewish community in the city. “They stayed and they are still getting support from the Jewish community.”

Olga said she had made contact with colleagues who have been pressured into taking up work at schools run by the Russians. “They were under pressure. They need to survive,” she says. “They told me that they burned all the Ukrainian books and teaching materials and replaced them.”

The Russian occupation is palpable in every way for those left behind in the city, Olga said.

“Mariupol is totally destroyed,” she said. “It is hard to communicate with people who are there. There is not always internet. They told me that they opened Russian shops with Russian products, but that they can’t afford them. These places are not affordable, because they don’t have money.”

In Luhansk, where Russian-backed separatists have been fighting the Ukrainians since 2014, the men of an already depleted Jewish community are living underground for fear of conscription.

“I speak to Luhansk every day,” says the exiled rabbi of Luhansk Shalom Gopin, a Chabad emissary who has been based largely elsewhere since 2015, amid the war that followed Russia’s first, more limited invasion. “It is a very bad situation there and there is a big problem with the men. The men don’t want to leave their homes because they can be conscripted and taken to the army.”

“The Jews don’t go out. If you don’t go out, they can’t come and get you and take you to the army,” said Gopin, who added that a few Luhansk Jews have been conscripted and that a small number have been killed at the front, fighting against the Ukrainian military.

Rabbi Shalom Gopin, the exiled rabbi of Luhansk, is at left, seen with two Chabad colleagues from Lviv and Dnipro in Lviv, September 2022. (Jacob Judah)

When war erupted in eastern Ukraine in 2014, the vast majority of Jews in the two regions that were partially occupied — Luhansk and Donetsk — left for elsewhere in Ukraine. That included Gopin, who left first for his native Israel and then for Kyiv. Those who remained, said Gopin, were either elderly or backed the Russians.

“There is a working community still in Luhansk that prays four times a week,” he added. “But this is not a community. It is old people, sick people, bad people. It is not a living community. It is a very bad community. There is no future.”

In areas of Luhansk that were Ukrainian-controlled before February 2022, the few Jews that lived there have been largely cut off, even though Gopin said he has managed to facilitate the evacuation of some Jews from occupied areas.

“They don’t have water, they don’t have gas, they don’t have internet. There are Russian flags all over the place,” said one woman from Lyschchansk, another city where a major battle was fought between Russian and Ukrainian forces, about her parents who remained there.

“There is no life and there is no prospect of life there,” she added. “They stayed because they would not give up their home and they said that their life was there, and they wanted to stay put. They won’t leave, it is useless trying to convince them.”

An aerial view of damaged sites in the eastern Ukraine city of Severodonetsk, which Russian forces took control of after sustained fighting, in Luhansk Oblast, Ukraine, July 9, 2022. (Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

She said her parents have been trying to formalize documentation for their apartment, which survived the battle, as many of those who have been rendered homeless have been moved by occupation authorities into houses abandoned by those who fled the city.

“They are making wood with fire, and they cook there. They promised that they would get gas, but that is their life now,” she added.

In Severodonetsk, a city that was occupied after a brutal urban battle between early May and late June, there had been eight Jewish families.

“I spoke to a good friend in Severodonetsk in mid-May,” said Gopin. “Since then, there has been no contact. We don’t know who is alive or what is going on.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.