(New York Jewish Week) — The Manhattan-based wine writer Alice Feiring has made several trips to Georgia, the former Soviet republic where, for thousands of years, wine has been fermented in sealed earthenware vessels known as qvevri.

Raised in an Orthodox Jewish home in Baldwin, Long Island and best known for championing “natural” wines, Feiring decided, in 2018, to bring a rabbi into Georgia to make kosher natural wine. Unfortunately, it turned out the cost was prohibitive.

Feiring hasn’t given up on her plan, and hopes to try again, perhaps next year, but this time in New York State with the Lubavitcher winemaker Yossi Zakon.

“I don’t really have this burning desire to be a winemaker,” Feiring told the New York Jewish Week, “but I do have a burning desire to bring a delicious natural kosher wine to the people.”

If she succeeds, the task will be partial redemption for a prodigal daughter whose path away from the observant Judaism of her family was traumatic. Feiring’s maternal grandfather, whom she adored, wouldn’t talk to her for the last two years of his life when he realized she was no longer “frum.” Feiring was 40 when she told her mother she no longer kept Shabbat according to Orthodox halacha, or Jewish law.

“My mother’s wrath was second only to my grandfather’s and I just hadn’t separated enough [from her] to be able to stand up to it,” she explained. “At a certain point I just said, ‘To hell with it. This is who I am.’”

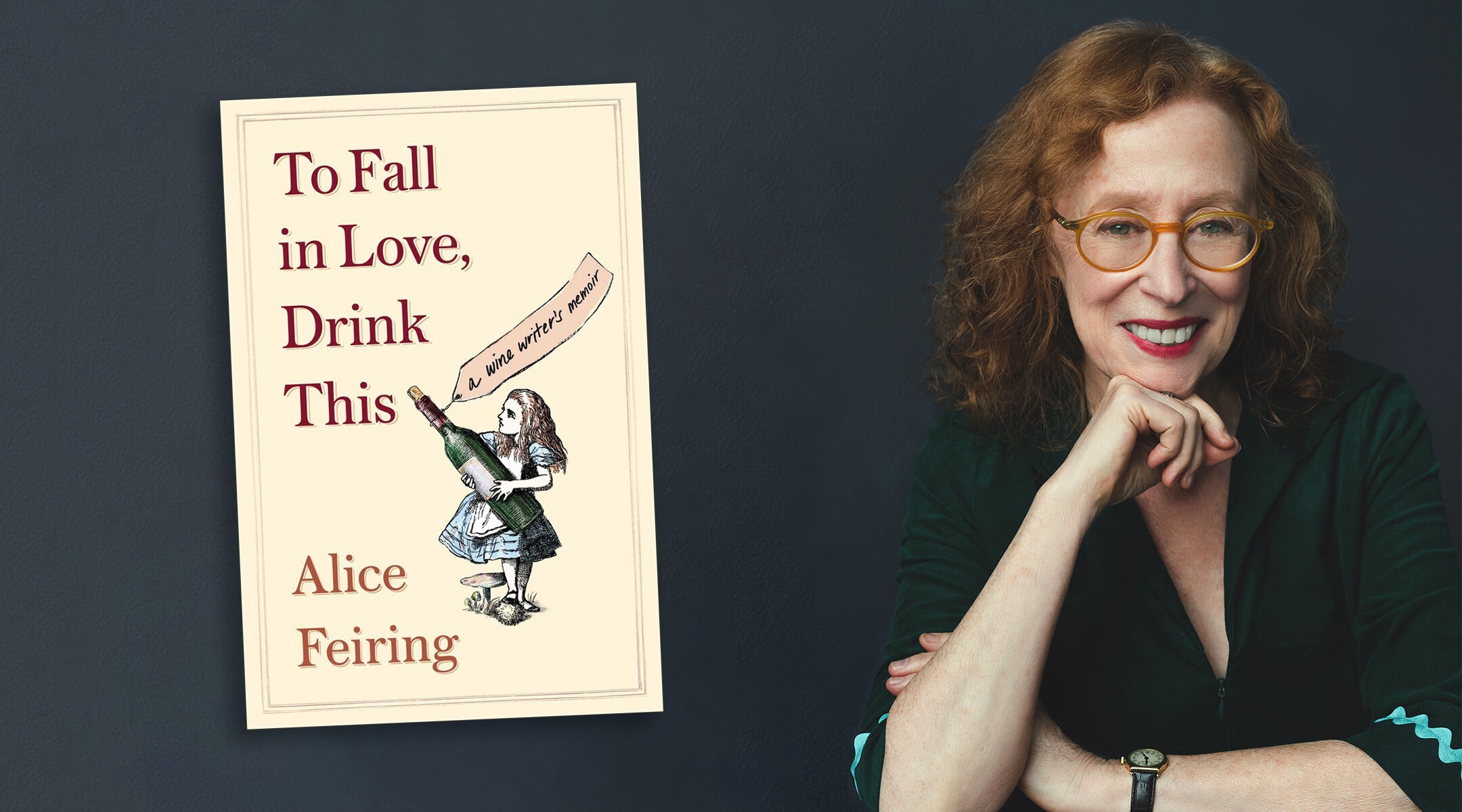

If nothing else, her family’s sometimes strained dynamics provide great grist for her new memoir, “To Fall In Love, Drink This” (Simon & Schuster). In addition to describing her adventures in the wine trade, the book explores her relationship with a caddish dad and what she describes as “not just any kind of Jewish mother but the Jewish mother.”

“Everyone had an Ethel in their terroir, who, though loving, made them feel maybe like they were not good enough,” writes Feiring, using the winemaker’s term for the environment in which grapes are grown.

For connoisseurs of natural wine, however, Feiring is more than good enough. She was the first to write about natural wines in America and, since 2013, writes the natural wine newsletter and blog The Feiring Line. On the way to becoming one of the industry’s most respected writers, she has been a wine and travel columnist for Time and a contributor to The New York Times, New York Magazine, Condé Nast Traveler and Forbes Traveler. In 2008, in a previous book, she took on the most powerful figure in wine criticism, Robert Parker, saying his famous points system for judging wines had led to the popularity of wines that were “soulless.”

“If you had a really happy childhood or an amazing parent, what have you got to write about?” asks wine writer and memoirist Alice Feiring. (Peter Zanger)

“She writes about wine as if it were a living thing — a character — that she is on the verge of understanding, if only it would hold still for a minute and stop surprising her,” the New York Times restaurant critic Pete Wells wrote on his Instagram page in September.

That passion is reflected in the memoir’s descriptions of various wines. “You can still taste the strength of the sun,” she writes of a 1982 Jaboulet Crozes-Hermitage. An Italian red wine called Barolo is “fragile, yet electric.” A syrah had hints of “olive, bacon, meat, blood herbs, laurel, rosemary and ‘cola without the sugar.’” Certain white wines have “a creaminess like sea foam,” she proclaims, and wines from a vineyard in Moravia possess a “monkey-like energy.” Oh-kay.

Her memoir also includes a fair share of bold-faced names, including the late, great African-American singer Nina Simone. Feiring tagged along with her photographer boyfriend for a photo shoot in Boston before a Simone concert in March 1986. The outspoken singer asked Feiring, who was fluent in Hebrew after 12 years of yeshiva education, to accompany her on an upcoming trip to Israel as an assistant and translator. The trip was postponed, then Simone offered Feiring a job as her accountant. Feiring turned down the gig.

More chilling was Feiring’s teenage encounter, in 1969, with a stranger who invited her back to his apartment in the East Village. Decades later Feiring learned that his real name was Rodney Alcala, who came to be known as the “Dating Game” Serial Killer because, amidst a killing spree that claimed at least seven victims, he was the winning bachelor on a 1978 episode of the popular TV game show. Alcala would lure his victims by offering to take their photographs. The terrified Feiring made the gutsy decision to attend Alcala’s 2012 trial in New York and then visit him at San Quentin Prison in California. Both acts were done at the urging of a New York homicide detective who hoped Feiring’s interaction with Alcala might yield more clues about unknown victims.

But time and again the book returns to the theme of family. Her mother may come off as difficult in the memoir but her father, whom she describes as being “a movie-star-handsome charmer” as a young man, is portrayed as a womanizing cad.

“If you had a really happy childhood or an amazing parent, what have you got to write about?” she asks.

Feiring and her brother Andrew were so conflicted about their father that when he died, they couldn’t decide on what to have carved on his gravestone.

“Both Andrew and I never learned the art of just saying something nice if it wasn’t true,” she said.

Six years after their father’s death, an aunt handled the engraving and made no mention of Philip Feiring’s wife or kids.

Alice Feiring refers to Andrew as her best friend and a father figure. He was every Jewish mother’s dream, a doctor. Feiring writes that she argued with God after her brother was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer; he was 62 when he died in 2013.

Feiring’s mother Ethel, who is Orthodox and lives in Queens, turns 98 next month. Two or three times a week her dutiful daughter makes the trek from her Little Italy railroad flat to visit her mother, who was furious when she learned that Alice was writing a memoir.

Ethel provides much of the drama in the book. Years ago, when Alice was dating a man who didn’t meet her mother’s approval, Ethel called Alice’s roommate complaining how Alice was twisting a knife in her heart.

“That was totally out of the Jewish mother playbook,” the writer said. And yet, when in the wake of Hurricane Sandy her mother pointed out that the parent-child relationship has been reversed, Feiring admits, “She’s such a pain in the ass, but sometimes she’s awfully cute.”

If there is a message in “To Fall In Love, Drink This,” it is that you can leave religion behind but still find meaning in the rituals and habits of kindness and caring.

Before her brother passed away, the two siblings Googled Andrew’s best friend, known as PZ, who lived across the street from their childhood home on Long Island. Alice once had a serious crush on the guy, who wore his dark hair in a ponytail and rode a motorcycle. Google had nuthin’.

About a month later, PZ passed her on the street in Manhattan. Forty years had gone by since they last saw each other. The white-haired PZ, who had become a radio engineer at a counter-culture radio station, had no trouble recognizing Feiring because her hair was still a beautiful red.

“It felt like we just summoned him up” by Googling him, she said. “It really did seem bashert [fated] to the max.”

When she told him Andrew was dying, he said he would be there for her.

“And he was,” Feiring said. PZ comforted her after her brother died, and the two became a couple.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.