(JTA) — Mike Hale ruined “The Gilded Age” for me. After reading his New York Times pan of the HBO series about Old New York — he called it ”a muddled and slapdash portrait … that consistently dips into caricature” — I figured there were plenty of other series worth my time and attention.

He did not, however, ruin the Gilded Age for me — that is, the actual historic period, roughly from the end of the Civil War to the end of the 19th century. Like many others, I am fascinated by the hallmarks of an excessive age: the lavish homes of the “robber barons,” the stultifying cultural codes of the high society “Four Hundred,” the literary treatments by Edith Wharton, Henry James and Booth Tarkington.

I am also appalled by the misery of the period: the abject poverty of the inner city captured in Jacob Riis’ photographs, for example, and the racist terrorism and white supremacist laws that ended Reconstruction. As the historians Adam Mendelsohn and Jonathan Sarna describe the age, it was a “giddy era marked by freedom and disenfranchisement, excess and immiseration, opportunity and exclusion, confidence and anxiety.”

What I rarely thought about was how Jews fit into this picture. I knew of figures such as August Belmont and the Lehman Brothers, who amassed great fortunes but were treated as arrivistes by the WASP elite. I knew Jewish immigrants from Romania and the Russian empire had begun to pour into New York by the 1880s, but I always felt their story belonged to the 20th century (when, not so coincidentally, my own grandparents arrived). When I read a Wharton novel, my encounters with Jews were both rare and unhappy.

Mendelsohn and Sarna have set out to restore the place of Jews in the post-Civil War period. They have edited the massive, forthcoming anthology, “Yearning to Breathe Free: Jews in the Gilded Age” (Princeton University Library). The title is taken, of course, from the poem inscribed at the base of the Statue of Liberty and written by the Jewish poet Emma Lazarus, as fascinating a Gilded Age figure if there ever was one.

Earlier this month, the American Jewish Historical Society in Manhattan put on a day-long conference, “Jews in the Gilded Age,” with panels featuring many of the authors who contributed to the new book. It was a bit like Comic Con for history nerds, or at least for buffs like me who regularly listen to New York history podcasts such as “The Bowery Boys” and its spinoff, Carl Raymond’s “The Gilded Gentleman.” Like the book, the symposium fleshed out a complicated era, especially in describing the seeds it planted for the American Jewish community as we know it today.

Historian Jonathan Sarna, co-editor of the new anthology “Yearning to Breathe Free,” and Zev Eleff of Gratz College speak on a panel on “Jews of the Gilded Age” at the American Jewish Historical Society in Manhattan, Oct. 2, 2022. (James Ferraro)

One big seed was the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, founded in 1886. Before it became the flagship of Conservative Judaism, JTS was an attempt by traditionalists to thwart the rise of the intimidatingly liberal Reform Judaism. Only later did it emerge as the “third way” of American Judaism between Reform and Orthodoxy, as Sarna discussed on a panel that included Rabbi Meir Soloveitchik of New York’s Congregation Shearith Israel and the current chancellor of JTS, Shuly Rubin Schwartz.

The enormous economic expansion of the age created enormous opportunities for Jews. Mendelsohn and a fellow panelist, Roger Horowitz of the Hagley Museum and Library, described the conditions that allowed even poor immigrants to get a leg up, from the exploding market for readymade clothing and cheap consumer goods to new industries like vaudeville, sheet music and the movies.

And as these “alrightniks” moved into the management class, Jewish workers began to organize in ways that anticipated the labor movement — and liberal voting patterns — of the 20th century. New wealth also liberated Jewish women from domestic labors; historians Pamela Nadell and Esther Shor discussed how Lazarus and the essayist Nina Morais Cohen used this freedom to defend their fellow Jews from burgeoning antisemitism.

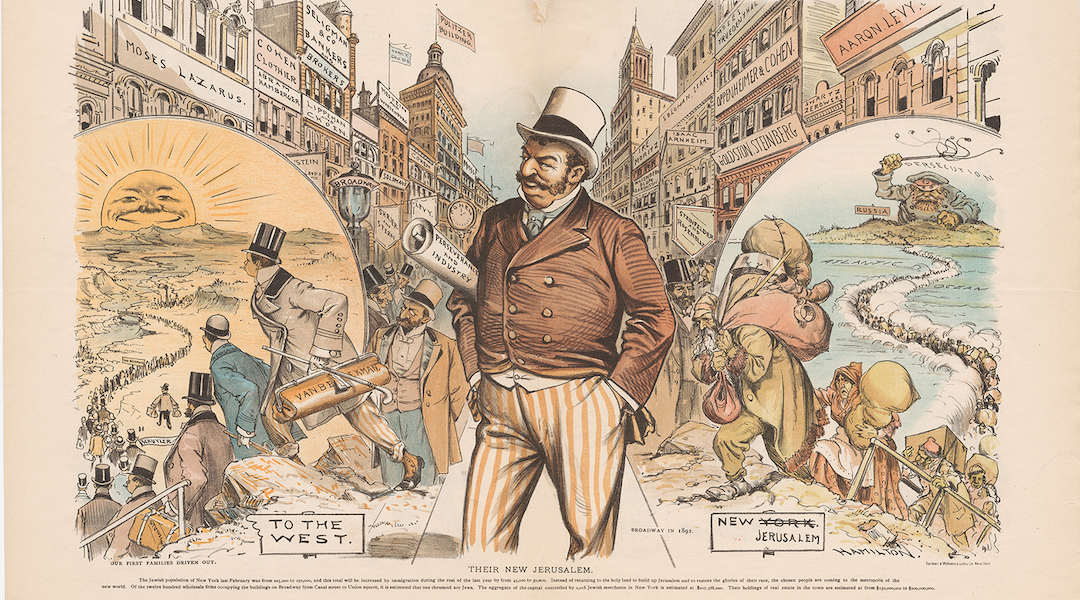

That antisemitism was the inevitable backlash to Jewish success. Yeshiva University’s Jeffrey Gurock spoke about the founding of the American Jewish Historical Society itself, saying that one of its main functions was “apologetics” — that is, chronicling and sometime exaggerating the Jewish contributions to the founding of the United States in order to counter growing antisemitism and anti-immigrant nativism. You recognize that insecure impulse today whenever a Jewish friend forwards a list of Jewish Nobel Prize-winners or the latest “proof” that Christopher Columbus was a Jew.

In a session on depictions of the Gilded Age in movies and television, Hale reiterated his criticism of the HBO series, but also noted the ways Jews in the series are “present by their absence.” The character George Russell is not identified as a Jew, but, as Hale and co-panelist Miriam Mora agreed, is “coded” Jewish by his attempt to break into old line New York society and the WASP characters’ attempts to keep him out. He is also one of the few characters in the series played by a Jewish actor, Morgan Spector (who also starred in HBO’s “The Plot Against America”).

Shuly Rubin Schwartz, chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary, speaks about Judaism in the Gilded Aged during a symposium at the American Jewish Historical Society in Manhattan, Oct. 2, 2022. (James Ferraro)

For Mora, director of programs at the Center for Jewish History, a more honest portrayal of the Gilded Age was Joan Micklin Silver’s 1975 film “Hester Street.” Set on the Lower East Side in 1896, the independent film dared to depict “Americanization as a negative.” Its protagonists are a striving Jewish husband who detests the Old Country, and a wife who is trying to hold on to her traditions. No saccharine Hollywood depiction of the Gilded Age — like “Meet Me in St. Louis” or “Hello Dolly!” — would have dared acknowledge these costs.

For many Jews today, the Gilded Age looks like a grainy black-and-white photograph, but instead of a lavish black-tie dinner at Delmonico’s it shows an ancestor standing in front of a store window advertising “full line groceries” and “jobbers of dry goods.”

Learning about the Jewish Gilded Age is like watching that photograph develop in a darkroom.

On the one hand the picture reveals the anxieties that still haunt us: antisemitism, internal divides, the high price of assimilation.

It’s also a portrait of success. As Benjamin Steiner writes in “Yearning to Breathe Free,” “Hard work, traditions of mutual aid, respect for education, centuries of diaspora experience, structural economic forces tied to capitalism and the fact that most Jews had white skins in a society where Blacks were the principal out-group — all enabled Jews by the middle of the twentieth century to become one of America’s most successful minority groups.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.