(New York Jewish Week) — Shoshi is a spirited young girl who always has her eye on the prize. In anticipation of her favorite Jewish holiday, Sukkot, she spends many sleepless nights planning for their town’s annual sukkah competition.

Shoshi and her brothers, Avram and David, live with their grandmother in the town of Mbale, in eastern Uganda, and they are members of the Jewish community known as the Abayudaya (meaning “People of Judah” in Luganda). They look forward to the sukkah competition all year long — but when a large storm destroys the beautiful, temporary dwellings constructed for the holiday, Shoshi steps up and eventually learns that working together with the community feels even better than winning.

So goes the plot of “The Very Best Sukkah: A Story from Uganda,” a new picture book published by Kalaniot Books that is based on the real-life experiences of its author, Shoshana Nambi, a first-time children’s book author and soon-to-be rabbi.

Nambi, 33, grew up in Abayudaya community, though she is currently living on the Upper West Side with her 13-year-old daughter, Emunah. After she receives her ordination from Hebrew Union College in 2024, Nambi plans to eventually return to Mbale to become the first female rabbi among the group of about 2,500 Jews.

The New York Jewish Week caught up with Nambi in the week before Sukkot, the week-long harvest holiday that begins Sunday night, Oct. 9. We spoke about the impact she hopes her debut book will have on both the Ugandan and U.S. Jewish communities, how Sukkot differs between Mbale and New York City, and about how writing a book about one of her favorite childhood stories was something she never expected to do.

This conversation has been edited lightly for length and clarity.

The author Shoshana Nambi, who is studying at Hebrew Union College – Jewish Institute of Religion to become a rabbi. Nambi grew up in the Abayudaya Jewish community in Eastern Uganda. (Courtesy Kalaniot Books)

New York Jewish Week: How and when did the idea come about to write a book about your childhood experience celebrating Sukkot in Uganda?

Shoshana Nambi: I never thought about writing a book. Communities would invite me to talk about my Jewish community, and at one Zoom event, somebody asked me to tell them about what I remember growing up. So the story — the story of the sukkah walk and us kids running around and looking at all the sukkahs that everybody had built — that’s the story I always have with me that I told [at the event].

Coincidentally, Lili Rosenstreich, my publisher with Kalaniot Books — and who has taught me a lot about writing a children’s book — was in the audience. She sent me an email later and said, “You could put that story into a children’s book.” I knew nothing about writing a children’s book. But I thought about it and I thought it was a wonderful idea for the community to be able to put our stories into writing, and for kids and parents to learn about the Abayudaya Jewish community of Uganda and about our Sukkot traditions.

In the very first line of the book you write: “Sukkot is Shoshi’s favorite Jewish holiday.” Why is it your favorite holiday, and how does Sukkot in Uganda compare to Sukkot in Israel, where you previously lived, or the United States?

At this point, I would say I have two or three favorite Jewish holidays — Passover, Sukkot and Yom Kippur. I loved Sukkot growing up. I love the idea of decorations. I love the idea of going and sitting in somebody else’s sukkah. I love this big walk [through the village]. I loved eating fruits hanging in people’s sukkahs. I loved the message of the rabbi about working together as a community. I loved the small competition. It was not an official competition — it was really, really informal. Nobody’s sukkah won, but usually, the whole group sat in somebody’s sukkah at the end of the walk. We all knew that was the best sukkah because usually it was where the rabbi ended up and where the walk ended, and we sang and did kiddush there. So I still love the holiday of Sukkot.

In each country, it’s almost similar, I would say. I liked that in Israel there are so many sukkahs when you walk around and you can see people actively building them. I haven’t seen that in New York City so much. Usually [in Israel or Uganda], when I come out of the house, there are sukkahs on the streets which are beautiful. In New York, we don’t have a sukkah here in the building, but I’m hoping to spend some time sitting and visiting schools to read my book in their sukkahs, and also celebrating at Congregation Rodeph Sholom’s sukkah, where I’m a rabbinic intern.

In Uganda, too, there is a big synagogue where people build a sukkah, and people come together to build it — people brought branches and trees and fruits and things to build, and actively dug holes and made the roof so they can say they were a part of it. Here, too, it’s just a little bit of a different process and probably materials as well — different fruits hanging, different decorations and different trees. But it’s mostly the same idea.

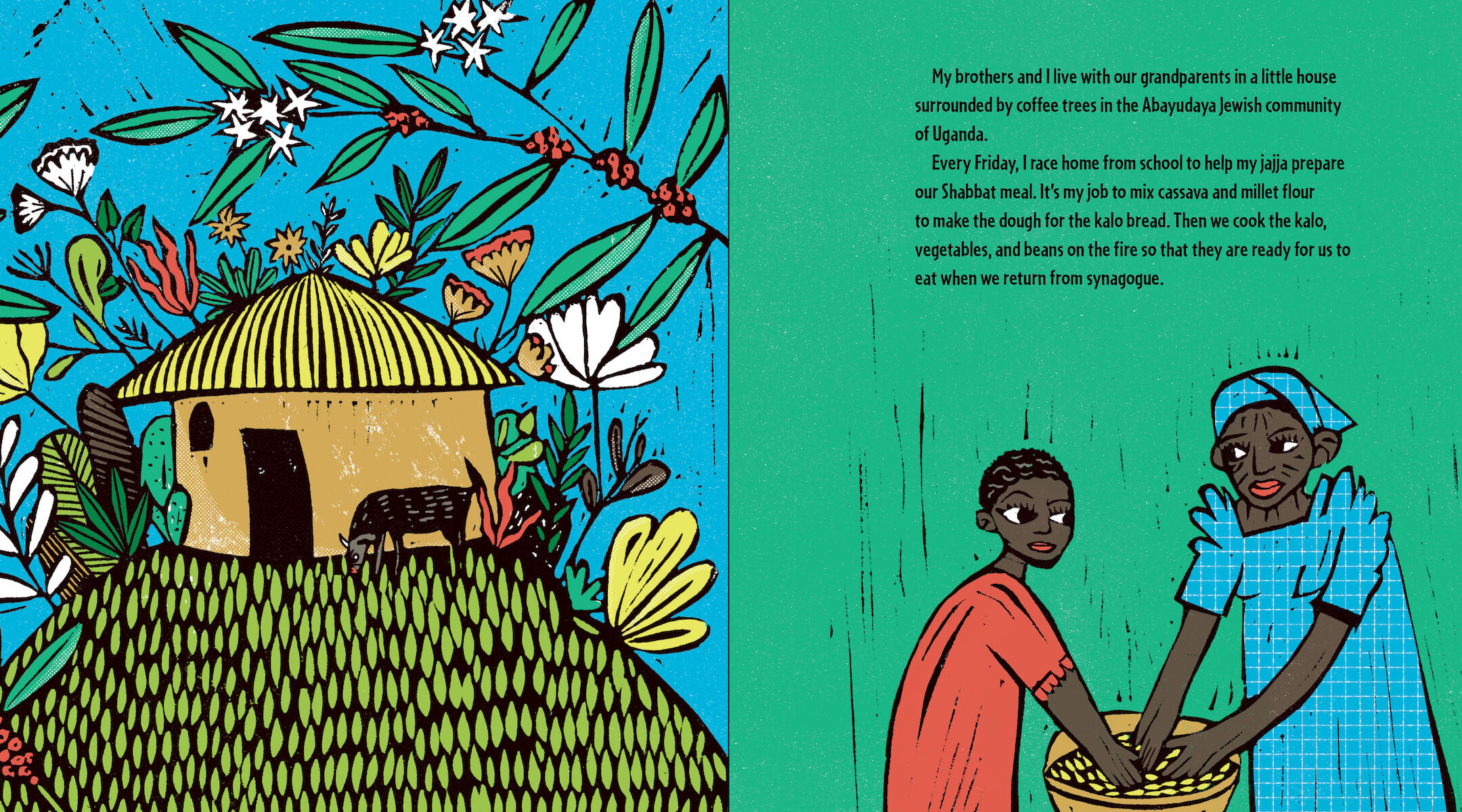

Let’s talk about the beautiful illustrations in your book. What does it feel like to see it come to life? What was the process of working with illustrator Moran Yogev like?

I love the illustrations as well. At first, I thought they were beautiful, but when Moran added color to them they were magnificent. We went back and forth. The colors were just amazing and I love how they bring out the brightly colored clothes of the people in Uganda. People love to wear bright colors and patterns and stuff like that. We wear traditional clothing that has 10 colors in one dress. I loved wearing brightly colored dresses and going to synagogue when I was young. I wore this smaller dress that was made from the remainder of my grandmother’s big dress.

So I love that, and I love that she incorporated the scenery — the rolling hills, the flowers and leaves, and that kind of beauty, which is very representative of the area where I come from. The area that the synagogue is in is called “The Hill” because it’s elevated and you can see the beautiful view of the surroundings and the slopes of Mt. Elgon.

The people around there are mostly farmers and so there are lots of plants, vegetables and trees. We also went back and forth about the physical features of people and how I really wanted people to appear. At first, she had sent me a picture of a rabbi and it was this big rabbi with a very long beard. I said, “I don’t think even if the rabbi had a beard it would even be that long.” It was fun working with her. She did an amazing job.

How does it feel to be able to bring this story that hasn’t been told before in a children’s book to your community?

It’s such a wonderful idea, and I’m so glad that the publisher reached out to me. I grew up not reading books at all. I went to a school with about 100 kids per class, only the teacher had a textbook or storybook so I never read children’s books growing up. Even in the [Abayudaya] community, there’s been some donations of books from the U.S. and Israel but there are no children’s books that have been written about the community by someone from the community.

For the kids to be able to see their Jewishness celebrated — their trees and their foods and how they decorate their sukkah, and the specific names like Nalango, which is the name that we call women who give birth to twins, and Daudi, which is how we pronounce David in Uganda — to have all of these things that are familiar to them be celebrated in a Jewish book is really, really important. I think that this is just the first [book] and we can keep going and maybe others can join me in writing.

Also, it’s important for kids here [in the United States] to learn about the Jewish community in Uganda. Not just kids, but caretakers, educators, parents, Jews and non-Jews. The value that we all win when we work together in our communities is a universal message.

Bonus question: You’ve said before that you plan to return to Uganda after receiving your ordination. What are your plans, and what does it mean to be a rabbi in the Abayudaya community?

I’m hoping to go back to Uganda at some point. My daughter is 13 right now and she’s in eighth grade at Schechter Manhattan. By the time I’m finished with rabbinical school, she will be in her first year of high school. I think I’m going to stay for another three years and maybe get a job here so she can finish high school and hopefully then go back home to Uganda.

My community is an egalitarian community and they’ve been open to women rabbis and teachers and leaders in the community for some time. It used to not be like that, but after we ordained our first rabbi, Rabbi Gershom Sizomu, he came back and had warm discussions with people about how he learned from his women professors and how he had wonderful chavrutas (small groups that study Talmudic texts together) and how things can be different when women are given chances. So things have really changed. I am proud to say that my community is very egalitarian in terms of community leadership. The only thing that I have to work on is I’m coming from a Reform seminary and my community is Conservative. That is something we can work on — I know the community very well, I know what they love learning about and how they like to pray and the songs we always sing in Uganda that are beautiful. These are the things that I want to continue when I go back.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.