(JTA) — For nearly a millennium, 17 Jewish children and adults lost to history at the bottom of a well kept a secret about the genetic markers that distinguish Ashkenazi Jews.

In 1190, in Norwich, a riverside city perched near England’s eastern coast, crusaders on their way to the Holy Land massacred 17 Jews and threw them down a well. The town was already a locus for antisemitic fervor: In 1144, its people originated the first known blood libel, blaming Jews for the ritual murder of a child.

In 2004, construction workers in the town, one of the most perfectly preserved medieval cities in the world, famous for its gardens and cobblestone streets, were clearing ground for a shopping center when they discovered the remains of the 17 children and adults. In 2011, initial DNA testing showed the skeletons were Jewish, and in 2013 they all received a Jewish burial.

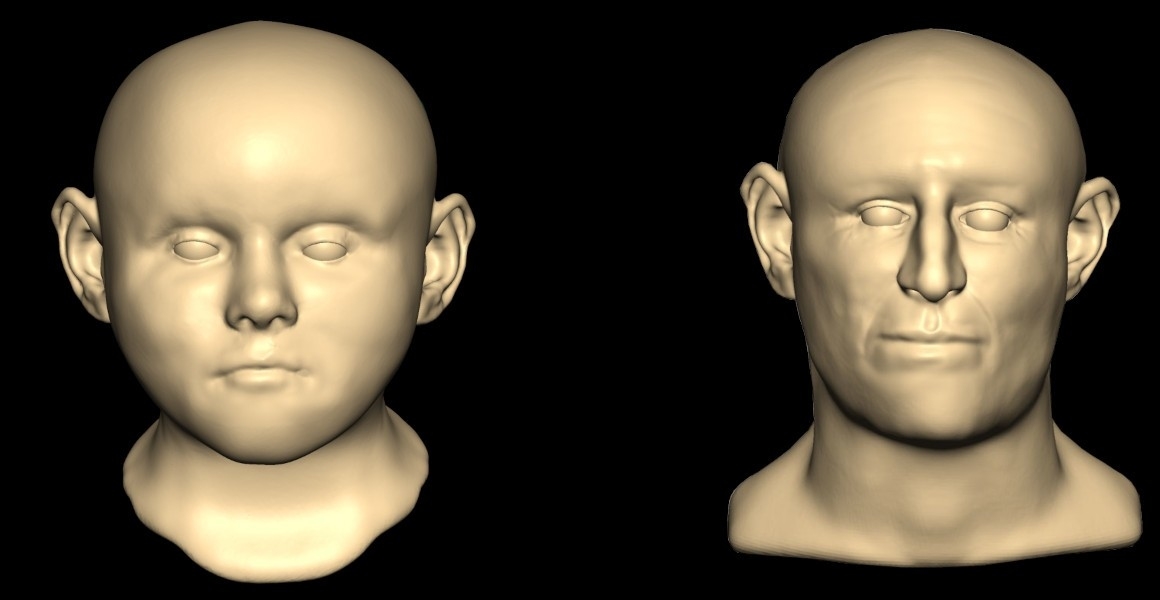

Now, a British study of the DNA extracted from the bones of six individuals prior to their identification as Jewish reveals that Ashkenazi Jews developed a unique genetic variation centuries earlier than realized.

Last week, Current Biology, a scientific periodical, posted the study led by Selina Brace of the Natural History Museum in London.

“When we look at the DNA from [the remains], they’re actually more closely associated to modern day Ashkenazi Jews than to any other modern population,” Brace told The Guardian.

Genetic variations among humans develop through “bottlenecks” when sudden reductions in populations increase the likelihood of inbreeding in a group. The Current Biology analysis notes several examples of these for Jews, including “the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, the formation of Ashkenazi communities in northern Europe during the medieval period, antisemitic persecution arising from the Crusades, unfounded reprisals for the Black Death, and the movement from western and central Europe to eastern Europe that preceded rapid population growth from the 15th to 18th centuries.”

Scientists had previously concluded that the bottleneck of about 350 Jews that created the genetic markers common among Ashkenazi Jews would have occurred about 700 years ago (the period of the Black Death). Tracking the origins of Jewish genetic markers is made difficult by ritual bans on unearthing the dead.

The study in Current Biology identifies genetic markers with “appreciable frequencies” among the Norwich dead, indicating that the mutations occurred much earlier. It uncovered four genetic disease alleles, or alternative forms of genes arising from mutations, which are still found among Ashkenazi Jews. Moreover, it also identified a three-year-old boy as having had red hair and blue eyes, a variation associated with Ashkenazi Jews at the time.

The study also adds heartbreaking detail to the massacre: In addition to the toddler, the bones include three sisters. One was a young adult, one was between 10 and 15 years old and another was between 5 and 10.

Among Norwich’s best-known landmarks is Elm Hill, a cobbled lane famous for its medieval buildings. (David C. Tomlinson/Getty Images)

The massacre of the Jews in Norwich is known because of the writings of Ralph de Diceto, the dean of London’s famed St. Paul’s Cathedral at the time, who chronicled with horror the savagery of his countrymen. “On February 6” of 1190 “all the Jews who were found in their own houses in Norwich” were butchered, he wrote. “It cannot be that so sad and fatal a death of the Jews can have pleased prudent men.”

But the recent discoveries made brought the tragedy into more acute focus, the scientists said.

“Ralph de Diceto’s account of the 1190 AD attacks is evocative, but a deep well containing the bodies of Jewish men, women, and especially children forces us to confront the real horror of what happened,” Tom Booth, a post-doctoral researcher at Harvard University who contributed to the study, told the Natural History Museum website.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.