(JTA) — In 2009, writer Glenn Kurtz was working on a novel about “someone who discovers an old piece of home movie footage in a flea market and becomes obsessed with identifying the people [in it],” he said in an interview earlier this year. As he started researching what happens to old film, he remembered that his family happened to possess some home movies and wondered what became of them.

This led him to a closet in his parents’ house in Palm Beach Gardens, Florida, where he unearthed a film of his grandparents’ vacation to Europe in 1938, on the eve of World War II. In the 14-minute film was a three-minute section of their visit to Kurtz’s grandfather’s home village of Nasielsk, Poland, a town whose Jewish community would be decimated by the Holocaust not long after. Kurtz had never heard about this trip, as his grandfather had died before he was born, and his grandmother did not often talk about the distant past.

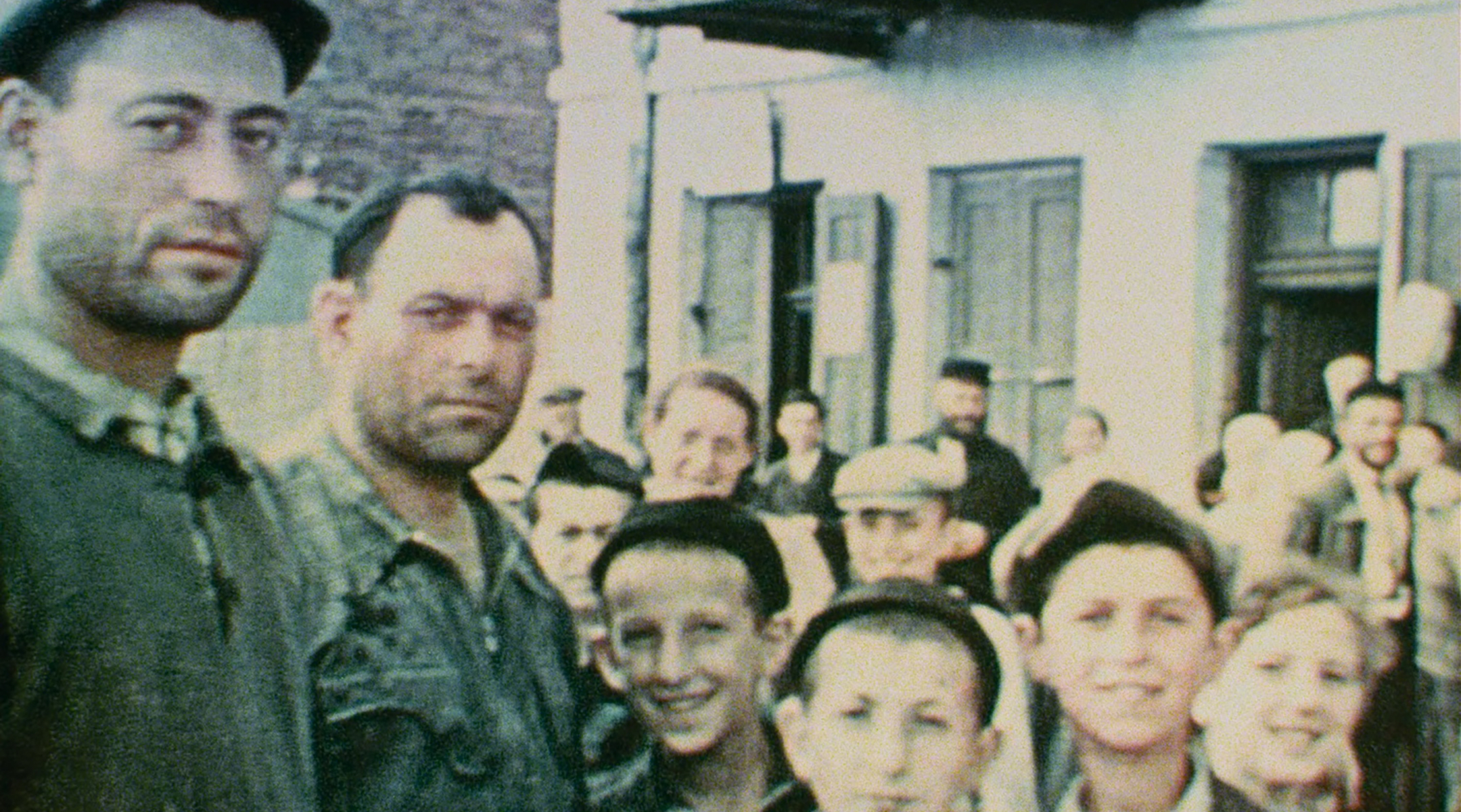

“Eventually, I had to abandon the novel, and I lived this story that I had been writing — I myself became obsessed with identifying the people who appeared in this film,” Kurtz said. “There’s hundreds of people, and lots of children, and I had this moment of shock when I realized, this is probably the only footage of these people — certainly the only color moving imagery… that exists. And I was now, in a way, responsible for their memory.”

The discovery led to four years of research into the footage, the people in it and what became of them, leading to the publication in 2014 of Kurtz’s acclaimed book “Three Minutes in Poland: Discovering a Lost World in a 1938 Family Film.”

“These three minutes of life were taken out of the flow of time,” Kurtz wrote in his book.

The home movie is now the basis for a feature documentary called “Three Minutes: A Lengthening,” directed by Bianca Stigter, who is also an historian and culture critic. The film, which appeared at the Toronto International and Sundance Film Festivals, as well as some Jewish ones, gets a wide theatrical release on Friday.

Glenn Kurtz spent four years researching the people who appeared in a family video he found at his family’s home in Florida. (Courtesy of Family Affair Films/US Holocaust Memorial Museum)

The documentary begins with the three-minute film itself, and then the rest of its 70-minute running time consists of parts of that footage with off-camera narration by Helena Bonham Carter and Kurtz, following the stories of specific people, locations and other things in the original home movie. The film does away with most documentary conventions, such as scenes of talking head historians or other related footage.

“I wanted this… raw power of this recording, to be the main focus and have the sense of stakes, and not dilute it with any talking heads, or other embellishments,” Stigter said.

One of the storylines follows Maurice Chandler, who survived the war. When Marcy Rosen watched the 1938 film on the Holocaust Museum website, she recognized her own grandfather, Chandler, in the footage, when he was 13. Chandler, now in his 90s, was interviewed for “Three Minutes: A Lengthening.”

“For me, it’s a historic document,” Stigter said. “But for him, it’s his past, his childhood, so he has a completely different relationship to the material than most viewers.”

The three-minute film itself was not in condition to be watched at the time that Kurtz found it, although Kurtz’s parents had at one point had his grandparents’ film collection transferred to VHS, and Kurtz first watched it in that format. Kurtz donated the original film to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, which was able to send it to a preservation lab and digitize every frame. That is the footage that is used in the new film.

Stigter had not previously directed a movie, although she has been an associate producer on films directed by her Oscar-winning husband Steve McQueen, including “12 Years a Slave” and “Widows.” The two are working on a documentary based on Stigter’s 2019 book “Atlas Of An Occupied City: Amsterdam 1940-1945.”

Much like another Holocaust-related documentary released this month, Stephen Edwards’ “Syndrome K,” the story of “Three Minutes: A Lengthening” started its journey to the screen when its director stumbled upon a Facebook post.

Around 2015, not long after Kurtz’s book was published, Stigter found a Facebook post about “Three Minutes in Poland,” and clicked on it, finding it a “very intriguing title,” Stigter told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in an interview. Learning that Kurtz had donated the three-minute film to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Stigter then watched it on the museum’s website.

“So I went over there, and watched the footage, and was immediately very drawn into it, because you see it in color, which is very rare for that time. You see these very vivid, vibrant street scenes, that I had never seen like that before. Children, really looking into the lens, and trying to stay in the frame, it has a very robust, joyous atmosphere,” she said.

Stigter thought it would be great to find some way to extend the footage, and got the opportunity not long after that, when she was asked to make a video essay by the International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR). The result was “Three Minutes Thirteen Minutes Thirty Minutes,” which ultimately formed the basis for the 70-minute “Three Minutes: A Lengthening.”

As for how many of the hundreds of people in the film were actually identified, Kurtz said somewhere between 25 and 30. In some cases, however, a person was recognized, but only remembered by a nickname, or some other partially identifying detail.

As part of her research for the film, Stigter visited the town in Poland itself, which allowed her to “solve some riddles” raised by the 1938 film, such as the name on one street sign. Some of the structures shown in the film remain, but the synagogue is no longer there, and there’s “not a lot of sense of the Jewish past,” she said.

However, she noted on a recent return visit to Nasielsk that a mural has been added, and that “the Jewish history of the town is now coming more to the fore,” which she attributed to Kurtz’s book and accompanying efforts to preserve the area’s Jewish cemetery.

What was it like for Stigter, who is not herself Jewish, to be immersed in the Holocaust for such a long period of time?

“Of course, sometimes it will hit you while you’re busy, you [get] realizations, sometimes. But at the same time, for me, the film works as a kind of tool against erasure,” she said. “Because there is so little known about what we see in the film, everything that you discover feels like a kind of small fix… for that erasure.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.