(JTA) — Five years ago, Rabbi Guy Austrian made a small but powerful change at the synagogue he leads: He wrote down the language his community used to call non-binary members to the Torah.

That language had been developed informally over time through a process that Austrian recalled as being “a little awkward” because it involved tweaking language on the fly for congregants whose gender did not fit into the male-female binary that’s baked into Hebrew.

Codifying the language meant changing only a few words of a formula in use in synagogues around the world, but it was essential to including people who are non-binary or otherwise do not identify as a man or woman, Austrian said.

“That makes the honor feel like an honor for the person who’s being called up for the Torah and for the congregation,” Austrian told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Now, Austrian —rabbi of the Fort Tryon Jewish Center in Upper Manhattan — is one of three authors of a religious opinion approved last week by the law committee of the Conservative movement that officially endorses gender-neutral language for Torah honors.

The opinion, called a teshuva, prescribes non-gendered language for three different honors, including the aliyah (the blessing before and after the Torah reading), hagbah (lifting the Torah) and gelilah (rolling up the Torah). It also includes procedures for calling up Cohens (descendants of the priests of the First Temple) and Levis (descendants of the tribe of Levi) as well as how to address people during the Mi Shebeirach prayer, without using gendered language.

According to the new teshuva, for example, a non-binary person who is called up for an aliyah, instead of being referred to as “ben” (son) or “bat” (daughter), is referred to as “m’beit” or “l’veit,” meaning “from the house of” their parents. The opinion notes that this construct has precedent in ketubahs — Jewish marriage contracts — and in the Hebrew vernacular.

The teshuva only affects rabbis and synagogues that are part of the Conservative movement, which claims about 26% of U.S. Jewish adults who identify with a denomination, and even there it’s not determinative: Some have already been using the language, and the approval does not require anyone to start.

Still, it reflects a notable change at a time when people who are gender non-conforming, including non-binary or transgender, are facing fierce opposition, especially from Republican lawmakers who have made 2022 a record year for anti-LGBTQ legislation nationwide.

“For those who are looking for an elegant and efficient solution and want to be able to have an inclusive community that honors people of all genders, this offers useful guidance,” Austrian said.

The authors of the opinion — along with Austrian, Rabbi Robert Scheinberg of the United Synagogue of Hoboken, New Jersey and Rabbi Deborah Silver of Shir Chadash in Metairie, Louisiana — say that in addition to drawing from Fort Tryon Jewish Center, they consulted variations of liturgy from LGBTQ synagogues such as Congregation Beit Simchat Torah in New York City and Congregation Sha’ar Zahav in San Francisco; Jewish organizations such as Keshet and TransTorah that focus on LGBTQ inclusion, and individuals who are trans or non-binary.

A delegation of Persian Jews and their friends marched at the Los Angeles Pride Parade in 2019. (Anna Falzetta)

The writers also note that they may not be the ideal authors of guidelines about how to mesh a contemporary understanding of gender with traditional Jewish law, because they themselves do not identify as non-binary.

“It’s just important to remember that this is an evolving terrain, both in society at large and within Jewish communities,” Austrian said. “So we don’t think that this teshuva is the last word. And we hope that as there are more non-binary, queer and transgender rabbis in the Rabbinical Assembly that they’ll be the ones who who write the teshuvot that will come.”

A diverse set of Jewish thinkers and clergy are already reshaping the role of gender in religious experience. In recent years, gender-neutral terms for traditional Jewish customs, such as the “b-mitzvah” in place of bar or bat mitzvah, have gained popularity. The Trans Halakha Project, which creates Jewish legal practices, customs and resources for trans Jews, launched just last year, an initiative of Svara, a Jewish learning group catering to queer Jews.

The new teshuva is a codification of a practice that has already existed in spaces led by trans and non-binary Jews, said Laynie Soloman, a non-binary rabbi and one of the co-founders of the Trans Halakha Project.

“I think it’s essential for halacha to be shaped by the people who it is about,” Solomon explained, referring to the disability activist community’s use of the phrase “nothing about us without us.”

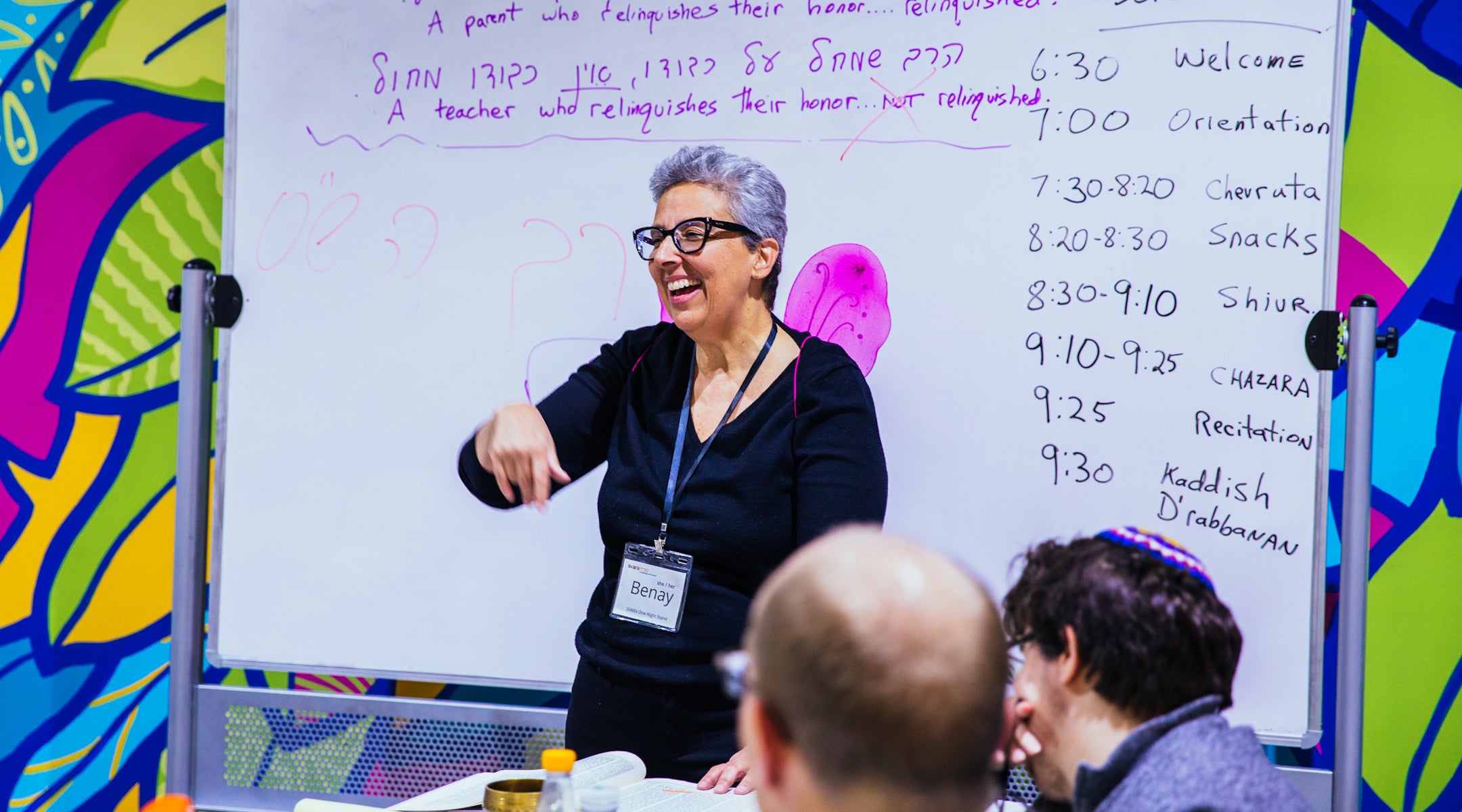

Rabbi Benay Lappe of Svara, whose Trans Halakha Project creates Jewish legal practices, customs and resources for trans Jews. (Jess Benjamin)

Soloman, who consulted on both the new Conservative teshuva and on the original liturgy from Fort Tryon Jewish Center, said, “We’re seeing the codification of minhag— of real custom and ritual that has been shaped by trans and non-binary folks. So while in the end, this happens to be written down by folks who are not trans or non-binary, this work was created by trans and non-binary folks. And that’s what’s so powerful to me about it.”

Meanwhile, people in both the United States and Israel have worked on creating a non-gendered version of Hebrew, a language in which nouns, adjectives and even verb conjugations carry masculine and feminine forms. One of them, Lior Gross, devised a way for non-binary people to speak Hebrew in part because they had trouble imagining being called to the Torah using the traditional, gendered script.

Like the other initiatives, the Conservative movement’s opinion represents an important development in inclusion in Jewish life, said Joshua Raclaw, an associate professor of linguistics at West Chester University in Pennsylvania who is non-binary and focuses on gender and sexuality in language.

Raclaw noted that gender non-conformity is embedded in Jewish tradition from its very inception. In the Book of Genesis, Adam is referred to as both “it” and “them,” even in the same sentence, he pointed out, adding that one 2nd-century rabbi specifically called Adam an “androgyne,” a term referring to a person with both masculine and feminine characteristics.

“While both Biblical and Modern Hebrew feature a grammatical gender binary, this tells us nothing about the genders that might exist among Hebrew speakers,” Raclaw said.

Then, using the Hebrew term for “repairing the world” that has come to mean social justice, they added, “But even beyond historical precedent, recognizing that non-binary Jews exist and creating pathways to further welcome us to the Torah seems to me to be a perfect example of tikkun olam.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.