(JTA) — K.M. DiColandrea had been teaching in New York City schools for well over a decade when he decided to become a student once again.

But just one semester after enrolling at Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, DiColandrea, who goes by DiCo, recognized that he had made a mistake.

“I realized that the way all my classmates were talking about becoming a rabbi someday was the way I already felt about being a teacher,” he told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Any lingering doubt DiCo may have had about returning to teaching social studies and debate was erased this week after one of his former students shared a story about him on Humans of New York, the photo storytelling project with tens of millions of followers worldwide.

In the story, Jonathan Conyers, now 27, described his difficult childhood in Harlem and how DiCo, his middle school debate coach, changed his life by helping him see value in his own story and choices. He also reflected on DiCo’s own life transitions, including his coming out as transgender while teaching at Jonathan’s school.

“Even today I thank God that DiCo was the first person I met who was transgender,” Conyers said in the story. “This was the only person who really loved and understood me. DiCo could have told me he was a dinosaur, and I’d be like: ‘That’s cool. Just stay DiCo.’ And the rest of the team felt the same way. A couple of the seniors gave him a hug, but then we just got back to debate.”

The website’s famously generous readers responded to Conyers’ 12-part story (with two codas from DiCo directly) by donating to the Brooklyn Debate League, a nonprofit that DiCo has run as a passion project and side gig since 2017, through his stints at a charter school, a Hebrew school and rabbinical school. A day and a half into the fundraiser, nearly 30,000 people had donated $1.2 million in total.

We spoke with DiCo about what that money will accomplish, how the 9/11 attack on the Twin Towers started him on a path toward Judaism, and what speech and debate have in common with Jewish ritual.

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

JTA: How did the Humans of New York story come to be, and what has it felt like to see it strike a chord with so many?

DiCo: It was all Jonathan. He was the one that reached out to Brandon [Stanton, who runs Humans of New York]. And he made a choice. The story didn’t have to be about me. Jonathan could just have easily made a whole story about him — he’s got this amazing story and he deserves so much credit for the phenomenal choices that he made in his life. But that’s not Jonathan.

Jonathan told me to brace myself for an emotional rollercoaster. I didn’t see the story in advance, so I was also reading it on Monday for the first time. And whatever I was expecting, my expectations were exceeded by a lot. I was blown away by the story. When you live it, you don’t stop to think about anything as extraordinary or special. It’s just what you do, especially as teachers — we do this all the time. I had forgotten some parts of the story to be honest, so when I really heard it from Jonathan’s point of view, I was really moved.

I’ve been putting in my own money every month [into the Brooklyn Debate League] to cover the payroll for our coaches and college students. I’ve been watching my bank account get lower and lower, so I was hoping to get at least paid back. But a million dollars, in a day? Wow.

What does that money mean for the program you run?

I have some ideas, but I want to make sure I’m not making decisions by myself. It’s important to me that this is not like the DiCo show — which is hilarious because it’s kind of what the HONY story has become. But I really want to make sure that we are making decisions as a community and that lots of different voices are being heard at the table.

Right off the bat, though I want to really up recruitment, and I don’t want to wait. I want to do it for our summer program.

I’m a New Yorker. I’ve lived here my whole life. I love this city. And I want to see what happens when we dramatically expand the access to speech and debate across New York City public schools, and particularly New York City high schools.

We know, from other districts around the country, what that looks like. After the Parkland school shooting in Florida a couple of years ago, you remember those kids that took to town halls and stood in front of thousands of people and were able to take on senators and just were able to speak up? That’s not an accident. The Broward County school district is maybe the only major school district in the country that offers speech and debate in every single school. Kids are given this gift of learning speech and debate as part of their regular curriculum. And I want to know what that would look like in New York.

In the story, Jonathan explores aspects of your identity. But even though a picture of you wearing a kippah appeared in the last installment of the story, your Jewish identity isn’t mentioned. What do you make of that?

There’s a simple answer to that. When I taught Jonathan, I wasn’t Jewish. I was raised Catholic, and then eight years ago, I converted to Judaism.

A couple things pushed me there. The first strike was Sept. 11. [At the time, DiCo was a junior at Stuyvesant High School in Lower Manhattan, blocks from the World Trade Center; he teaches at Stuyvesant now.] I found myself asking: What kind of God would let this happen? How did I just watch thousands of people die — people I just took the subway with this morning? Where was God?

That was the first strike and then strike two was related to what Jonathan talked about: coming out. I liked girls in college, and then I liked dressing as a guy after college and then I figured out gender in addition to sexuality. And it felt like there was less and less a place for me to be my authentic self at my church.

I was very religious: I was in my children’s choir from third grade up at church. By the time I was in eighth grade, I was an assistant organist. And by the time I got back from college, I was the assistant director and I was helping to run the children’s choir. I loved religion and my religious community, but when I came out it got a little more complicated.

By the time Jonathan showed up in my life, I was wearing men’s clothing, but I would have to change between school and choir practice. So I ended up leaving the church, but I missed having a religious community. I could have gone to just a different [Christian] denomination, but I kept coming back to a college course I took on the New Testament. It was the first time I realized that you could read a religious text analytically. I was like, whoa! This combines two of my favorite pieces of myself: the part that is super spiritual and religious, and the part that is super nerdy analytical, and I didn’t know you could do that.

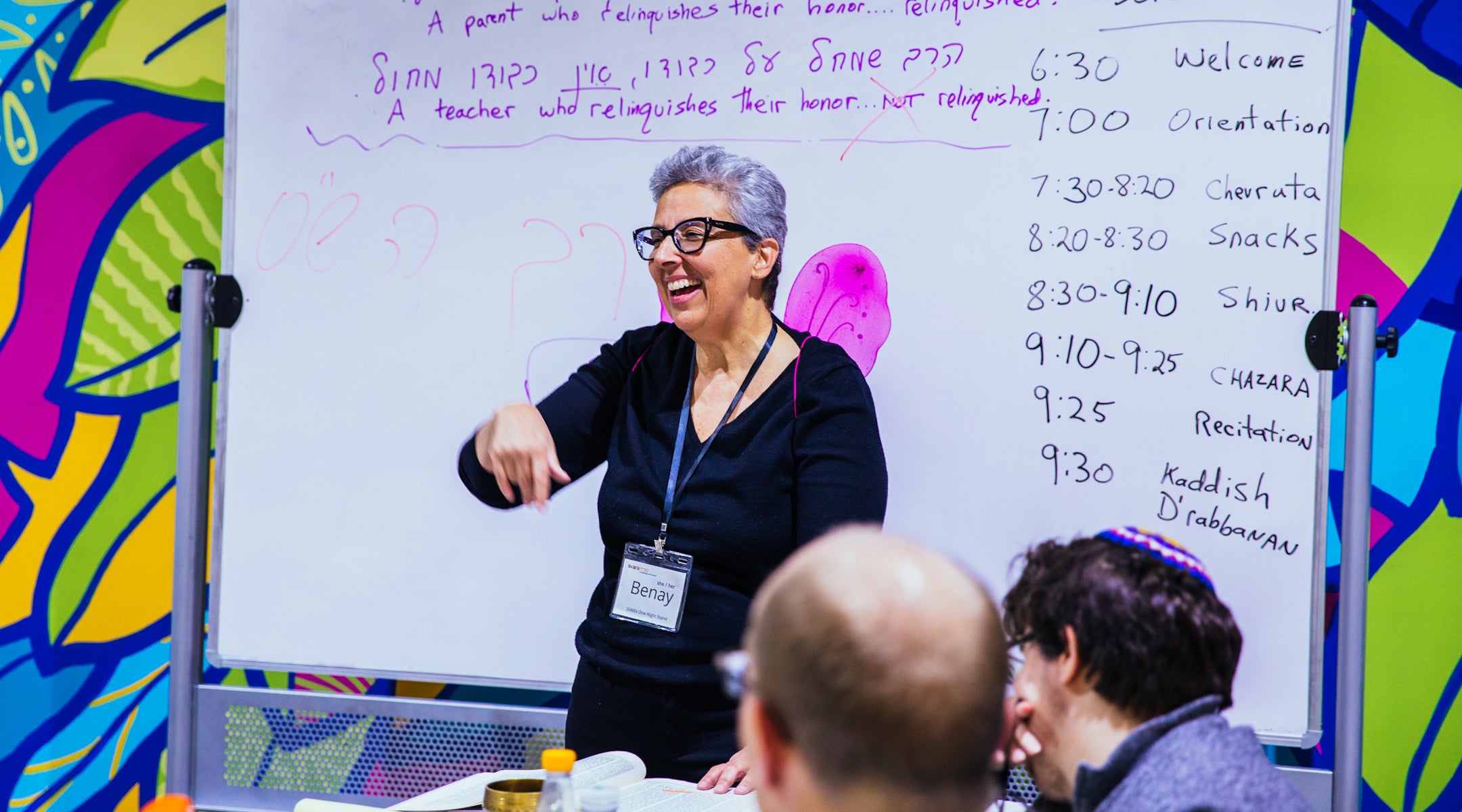

So when I found myself years later missing a religious community, what I was looking for was a place where I could be in spiritual community with other people and also just be a total nerd about it. I googled “Torah study near me” and found Congregation Beth Elohim [in Park Slope, Brooklyn]. I didn’t know anybody there, but I just kept coming back week after week and loved it. Later, after I converted, I found Svara, the queer Torah camp [now a yeshiva], and that was a total game-changer for me. Now I’m studying Talmud every day with another trans Jew, and I am digging it.

Rabbi Benay Lappe founded Svara as a space for LGBTQ Jews to study Talmud. (Jess Benjamin)

But what was really the icing on the cake was when I found out about the origin story of modern Judaism. I learned about the Temple falling and I was like, wait, do you mean to tell me that this is a people that also watched the world fall down and then never forgot about it, but found a way to be resilient and found a way to to live through that and survive that? That was it for me. I was like, I’m sold. This is where I want to be.

Catholicism and a lot of Christianity, it’s all about what happens next, about the next life and redemption that will come later. But having experienced what I did when I was a teenager watching the Twin Towers fall a couple blocks away, I didn’t have time to wait. I needed to process this now. I had felt such community with that Torah study group at CBE. But then I started feeling community with, like, Yohanan ben Zakkai and the rabbis of the first century, who had also experienced this trauma and had asked themselves the same questions I had: What the hell are we supposed to do now? How can we move forward from this? They found a way to do it, and that gave me a path to Judaism.

You didn’t just become Jewish but you became a professional Jew, including an educator who won a prestigious award from the Jewish Education Project. Can you tell me about that, and also about why you decided that becoming a rabbi wasn’t for you?

In 2019, I actually left my school and I left the debate team that I was coaching to go teach at my synagogue. I taught at CBE for a year, and then I became the assistant director of their religious school for another year. [Unusually for American supplemental Hebrew schools, teachers in CBE’s Yachad school are employed full-time.] I left from there to go to rabbinical school. I was in rabbinical school for a semester last fall, at Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, and I loved it. But I realized that the way all my classmates were talking about becoming a rabbi someday was the way I already felt about being a teacher.

Think about the calendar year. My classmates would be talking about how certain seasons would get them excited for certain holidays. For me, certain seasons and certain times of the year get me really excited — but about tournaments that are coming up. For my classmates, September is always Rosh Hashanah coming up; for me, September is always the Yale tournament. December’s Hanukkah — but December is the Princeton tournament. It makes sense, because we all mark the passage of time using different rituals.

Or about Saturdays. I’ve been working with CBE as a tutor for b’nei mitzvah students with their divrei Torah. Obviously I love helping kids write speeches. And I like the Saturdays where I get to be at services. But I have to be at tournaments on Saturdays. It’s a similar feeling of, it’s a ritual. It feels sacred. It gives me purpose, and it grounds me.

You taught in an after-school Hebrew school, a much maligned feature of American Judaism. What’s your prescription for great Jewish learning for kids?

I think not just Jewish education, but all good education, has to prioritize building a positive culture in classrooms. Kids aren’t going to like your class if they think that you don’t like them. They’re not going to want to be there if they think that you don’t want to see them. Good luck getting them to talk if they think you don’t want to hear what they have to say.

On top of that, specific to the Hebrew school component, you have to make it fun for them. The kids are in school all day and they’re exhausted. You’ve got to bring the energy, to bring whatever invests them. And I find that like a surefire way to make anything fun for a middle schooler or even high schoolers really, is to make sure that they’re doing more talking than you are. If you’re asking questions and kids are talking and debating and disagreeing and getting to push their thinking and push other kids’ thinking, then it gets interesting. The advice that I give to new teachers is: Most of your sentences should end in a question mark.

I didn’t go to Hebrew school. But it really seems that everybody I talk to thinks we’re missing an opportunity to really get Jewish kids excited about their heritage, and specifically in a text-based way. When I talk to Jewish kids about the Torah and Talmud, kids become bananas for it. Most of the time, they’ve never learned any of this stuff and they’re like, “Wow, that’s so cool. I never thought about it that way.” It’s so rich, and it’s ours. So I don’t think we have to reinvent the wheel here in terms of getting kids invested in Hebrew school — Torah is right there, and it’s so, so interesting. We just have to figure out how do we make it accessible for our kids in a way that gets them excited?

For our New York viewers specifically, is there a moment or a place in New York that has made you think: I’m really experiencing the gift of being a New York Jew?

Well, the best Israeli food in New York is at Miriam in Park Slope.

But my real answer is CBE. My whole Jewish journey happened in that building. It’s where I went to my first Torah study and my first services. It’s where I converted. It’s where I got married. It’s where I became a b mitzvah. It’s where I ran the religious school and was director of religious school and I taught there and it feels sacred to me, and I miss it. I can’t wait for the day when I can be back inside the CBE sanctuary regularly.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.