(New York Jewish Week) — Not to be a buzz kill, but I’ve never been much of a pot smoker and don’t intend to start.

But I do love Jewish material culture and learning about unexplored byways of Jewish history, which is why I am excited about a new exhibit at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research dedicated to Jews and cannabis. “Am Yisrael High” (see what they did there?) displays texts and artifacts tracing the connections — some speculative and most very real — between Jews and weed, and how an often taboo subject and substance has intersected with religion, politics, crime and science.

On Friday I spoke with the curator, Eddy Portnoy, who is the academic advisor for YIVO’s Max Weinreich Center and its exhibition curator. Portnoy also maintains one of my favorite Twitter feeds, in which he shares unusual and sometimes wacky artifacts from YIVO’s archives – which, like the weed exhibit, never fail to remind viewers like me of the strange, unexplored possibilities of being Jewish.

The exhibit opens May 5 at the Center for Jewish History, 15 West 16th St. in Manhattan.

Our conversation was condensed and edited for length and clarity.

New York Jewish Week: We should get this out of the way first: Is weed kosher? What is the traditional Jewish attitude towards intoxication and psychoactive substances?

Eddy Portnoy: It depends on whom you speak to, but in the main, at least as far as Orthodox Judaism is concerned, recreational use of cannabis is not acceptable. However, medicinal use is. This goes along with cigarettes in that smoking is bad for you, and you’re not supposed to harm your body. But because legalization is a relatively new phenomenon, that ultimately changes things. The principle is “dina d’malchuta dina” — obedience to the civil law of the country is religiously mandated. So some rabbis will say, if this is legal to do, this is acceptable.

So it is more about health than an aversion to altered states?

Scholars believe that certain Kabbalists in Morocco, in North Africa, did use hashish because it was considered to have elevated their consciousness in some way. But it was for a religious purpose. It wasn’t for recreation.

What got you started on this? And by this I mean, an exhibit devoted to Jews and weed.

I smoked a lot of pot in college, but stopped after I had kids. I didn’t think it was responsible to be high around little kids.

About two years ago, I stumbled across a glass bong in the shape of a menorah. It’s like a sculpture. Obviously, you would never really think of smoking eight bowls, but I thought to myself, I work at a historical research institute, and YIVO has been collecting Jewish material culture for almost 100 years. And this object brings together both Jewish religious culture and contemporary cannabis culture in a way that I had never really seen before. So I contacted GRAV, the company that makes it. And once it was in my office, I asked myself, is this just a kitsch item, or is there a real history behind Jews and cannabis?

So let’s go back in history with a term featured in the exhibit. What is kaneh bosem?

It appears in Exodus [as an ingredient in “sacred anointing oil”], it appears in a number of different traditional texts and rabbinic literature. It is typically translated as “fragrant reed” or aromatic cane, and sometimes as calamus. In the Mishneh Torah, [the medieval sage] Rambam translates kaneh bosem as Indian hemp, which is cannabis. Kaneh bosem even sounds like cannabis. There’s a scholar who claims that the word comes from the Scythian word for cannabis, and the Scythians were known to have used cannabis in their religious rituals, as did multiple ethnic groups throughout the Middle East for thousands of years.

About two years ago, Israeli archaeologists found and excavated third-century BCE synagogue sites at Tel Arad. They found two altars that had the burned residue of certain material, which they took for chemical analysis and carbon dating. They found on one altar the burn residue of frankincense and on the other the burned residue of cannabis.

Archaeologists digging at Tel Arad in Israel found an altar, left, that had residue from burnt cannabis. (Israel Antiquities Authority, Photo © The Israel Museum, by Laura Lachman, courtesy YIVO)

And that would have been about the same time as the first Jewish Temple in Jerusalem.

Nachmanides, in his commentaries on Exodus, appears to say that kaneh bosem is cannabis and that it was one of the ingredients in ketoret, the incense offering in the Temple.

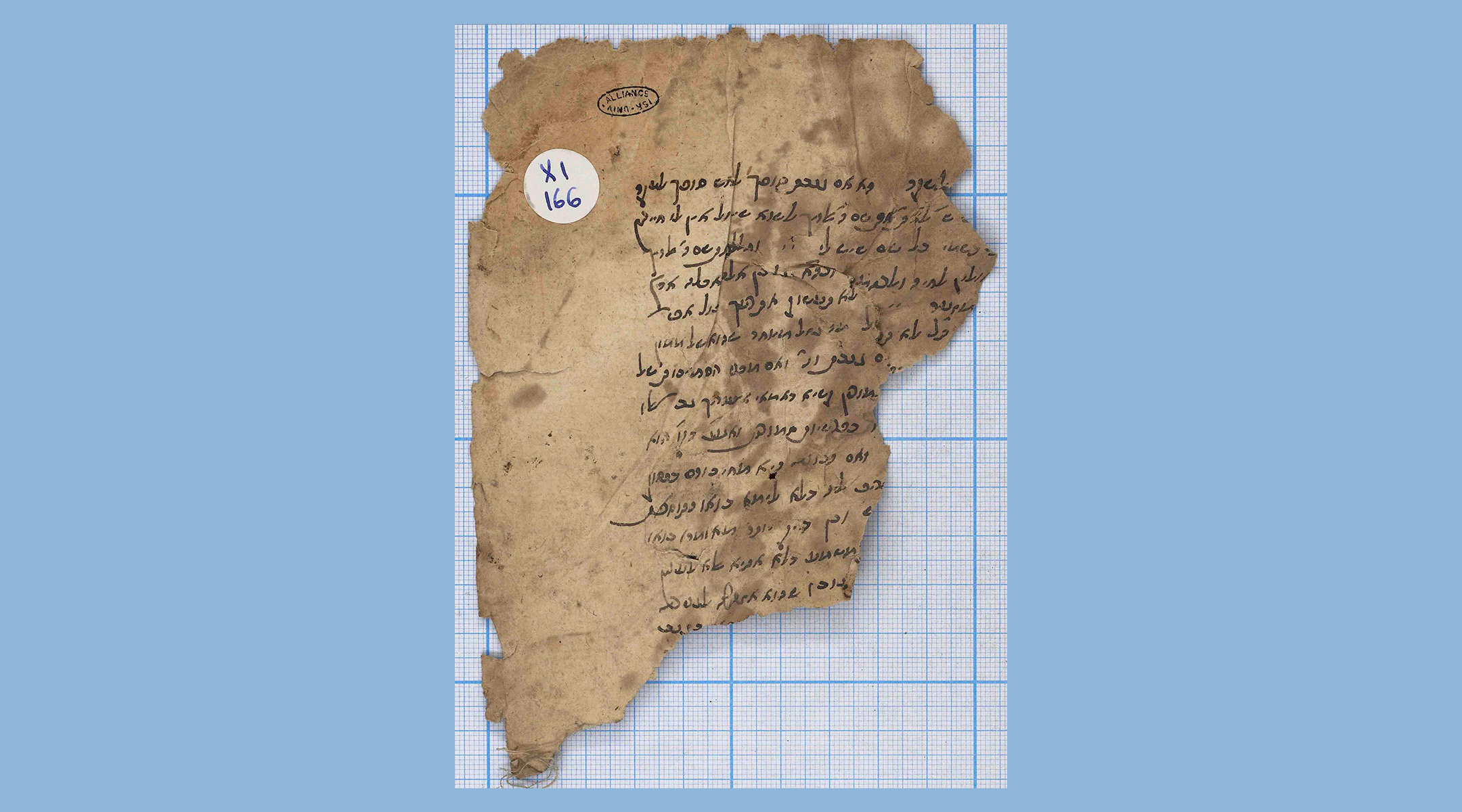

To skip ahead a bit, you display a purchase order for pot found in the Cairo Geniza, the synagogue storehouse that dates to the 12th or 13th century.

There are a number of documents from the collection of the Cairo Geniza that reference hashish. This one is a note in Judeo-Arabic that confirms that an “esteemed elder” received “two carats of ingot silver,” to be used to “obtain hashish for me with them.” It’s the 13th-century version of someone Venmoing someone and saying, “Please get me some weed,” indicating that Jews were using hashish, for whatever reason – recreation or medicine.

For the exhibit I realized I had to go where cannabis was part of the general culture, and that meant the Middle East and North Africa. One Israeli scholar of Moroccan Jewry told me that it was a tradition for Moroccan Jews to sprinkle hashish in the couscous at wedding parties.

A document recovered from the Cairo Geniza (12th-13th centuries CE) thanks a traveler for acquiring hashish for the letter writer. (Alliance Israelite Universelle, Paris)

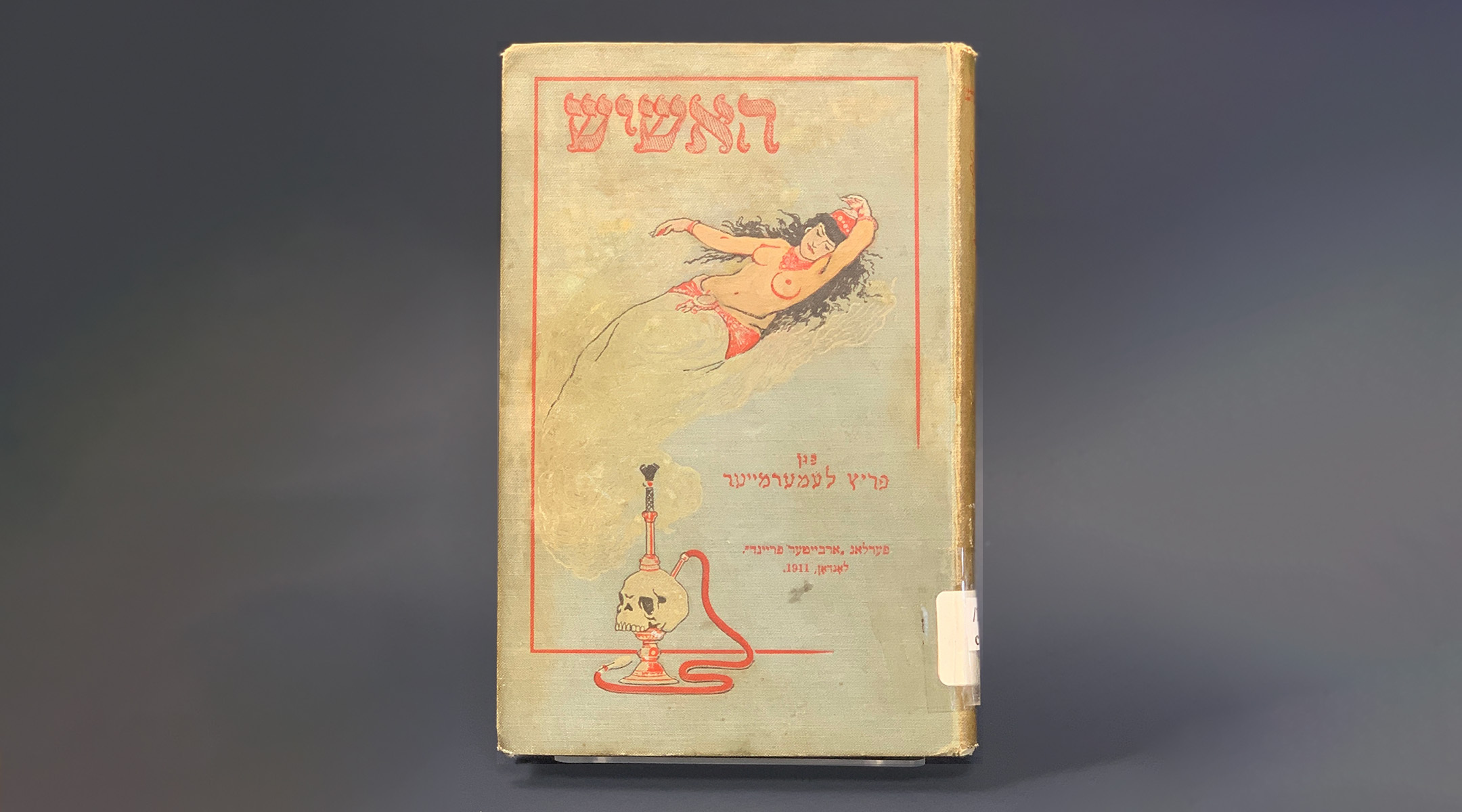

You also have artifacts from Ashkenazi culture, like a Yiddish-language book called “Hashish.”

That is a 1911 translation of an 1879 German novel, a kind of “One Thousand and One Nights” Orientalist fantasy. It was translated by Rudolf Rocker, a well-known anarchist who wasn’t Jewish, but learned Yiddish so he could, you know, do kiruv [recruiting] among Jews for anarchism.

But the reality is, in Yiddish culture and Eastern European Jewry, pre-World War II there’s not much connected to cannabis use. Moyshe Nadir, the well-known Yiddish satirist [1885–1943], has a short story called “Hashish” in which he visits a Jewish artist in Greenwich Village who smokes hashish. Occasionally in the Polish Yiddish press, sometimes the American, you’ll find an article about a drug bust in which Jews are involved.

There is one guy [Yoseph Leib Ibn Mardachya] who wrote a book called “Cannabis Chassidis,” and one of the arguments that he makes is that all the early Hasidic masters smoked pipes, and their acolytes all wrote that when they smoke their pipes, they went into ecstasy. I don’t know how much evidence there is to prove that. Vladimir Jabotinsky wrote an ode to hashish in 1901 when he was a student in Vienna. It’s an anomaly, but it is in the exhibit.

“Hashish” is a 1911 Yiddish translation of an 1879 German novel. (YIVO)

But the Jewish connection is really strong starting in the 1960s, when marijuana is deeply tied up with the counterculture.

One of the items we have in the exhibit from the 1960s is a press release from an organization called LeMar, which stands for “Legalization of Marijuana,” an organization that was co-founded by poet Allen Ginsberg, who was really a central figure in both cannabis advocacy and the legalization movement. LeMar was the first legalization organization created in America. Ginsberg participated in legalization rallies in 1964, long before anyone started to do this.

Jews seem to play an outsized role in the counterculture. The Yippies were founded by five Jews: Abbie Hoffman, his wife Anita Hoffman, Nancy Kurshan, Jerry Rubin and Paul Krasner. I had no idea what a central issue marijuana legalization was for them. In virtually every issue of The Yipster Times, their newspaper from the 1970s, there are articles about cannabis. Their official flag is a black flag with a red star that has a marijuana leaf embossed on it. It’s not clear that there was any Jewish content in that regard, religious or cultural, but Jews were at the forefront of this counter-cultural movement and this is one of the things they promoted.

You also deal with the serious side of cannabis, specifically the medicinal side and the Israeli researchers who are at the forefront of the science.

Raphael Mechoulam is an Israeli chemist who was the first scientist to isolate THC as the component that produces euphoria, and CBD as well. This was in the early 1960s. He’s worked on cannabis his entire life, and in the 1990s he and his colleagues discovered the endocannabinoid system, which regulates homeostasis – a significant discovery how the human body deals with cannabinoids. I read an interview with him where he says that because he was in a small country, he would have to find a niche that other people weren’t working in.

Lester Greenspoon was a Harvard University psychiatry professor who in the late 1960s set out to do research on cannabis when there was a significant taboo on doing research in this area – it was the “reefer madness” era. And yet Greenspoon decided to do research to determine whether cannabis was detrimental or beneficial. And his research indicated that it was not only not detrimental, but it could have medicinal benefits. He produced a book in 1971 called “Marihuana Reconsidered” and it was published by Harvard University Press.

I have to add that to a certain degree Greenspoon was influenced to both work on cannabis and also to try it by his close friend, the Jewish astrophysicist Carl Sagan, who was a huge pot smoker. Both Carl Sagan and his wife Ann Druyan were very much advocates for cannabis. Sagan wrote the introduction to “Marijuana Reconsidered,” although under the name “Mr. X.”

A rolling tray from Tokin’ Jew, which borrows its design from the seder plate, is featured in YIVO’s latest exhibit, “Am Yisrael High: The Story of Jews and Cannabis.” (YIVO)

YIVO is associated with preserving the culture of Eastern European Jews and remembering what was lost in the Holocaust. At any point did your bosses say, “This exhibit is just not who we are?”

No one said that … exactly. But when I described the idea and explained that it would be contextualized historically, they thought that this would be an acceptable way to present this. I mean, it’s legal – not in all states, but that seems to be the trajectory. It’s a multi-billion dollar industry. It’s becoming part of the general culture. The focus is really on Jews in a particular industry. It could be the film industry, it could be the comic book industry. If an exhibit is contextualized adequately, you could do virtually anything.

I want to ask you something a little bit off topic, but I think it relates: your Twitter feed. You present all kinds of oddball Yiddish and Jewish objects, which I think may have the same intent as this exhibit, which is opening up an audience’s eyes to the possibilities of Jewish culture and a deeper understanding of who the Jewish people are.

Because I work at YIVO, I’m constantly coming across fascinating and unusual images or objects connected to Jewish history. And sometimes these weird things that I find in YIVO collections wind up taking off in ways that I don’t anticipate. It’s a great benefit because it helps people understand what this place is and what it has.

The opening of “Am Yisrael High: The Story of Jews and Cannabis,” will feature a panel discussion, in person and via Zoom, moderated by Eddy Portnoy and featuring Ed Rosenthal, Adriana Kertzer, Rabbi Dr. Yosef Glassman and Madison Margolin. Thursday May 5, 7 p.m. ET.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.