(JTA) – On Feb. 24, two shipping containers laden with 20,000 pounds of shmura matzah were slated to head out of port in Odessa, Ukraine, on their way to Orthodox Jews in the United States.

Two hours before they were to be loaded onto a ship, Russia invaded.

The shipment was the last of 200,000 pounds of unleavened bread that Ukrainian matzah bakeries shipped to the United States this year, in addition to what they ship to Europe and Israel.

Now, technically outside of Ukraine’s customs zone, it could neither be returned to the country nor travel on to the United States.

Rabbi Meyer Stambler, head of the Chabad-affiliated Federation of Jewish Communities of Ukraine, estimates that his factories in Ukraine account for about 15-20% of the U.S. market share for shmura matzah, the carefully “handmade” variety that many observant Jews prefer to use during the seder.

A factory worker makes shmura matzah under supervision in Ukraine. (Courtesy of Meyer Stambler)

Shmura matzah is handmade in small batches with a higher level of supervision than most other types of matzah. That already makes it significantly more expensive than the factory stuff. A single pound box of shmura matzah could go from anywhere between $20 and $60, the Forward reported in 2018. In contrast, Instacart offers at least three different brands of regular matzah that come in under $10 for a 5-lb. box.

“I think the U.S. market will feel it,” Stambler told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “I think we are probably going to have a deficit of shmura matzah this year.”

RELATED: All of our ongoing Jewish Ukraine coverage

The vast majority of shmura matzah produced abroad had already made it to the United States before the end of February, suggesting that the war in Ukraine is unlikely to be a major disruption. But an already overextended shipping industry after two years of pandemic, combined with rising gas and labor costs, have fueled rising prices for the matzah.

Barely over a month ago, Stambler would have said business was booming. “This year, we even opened a new matzah bakery, another branch, in Uman,” he said, referring to the Ukrainian city that is a pilgrimage site for Hasidic Jews.

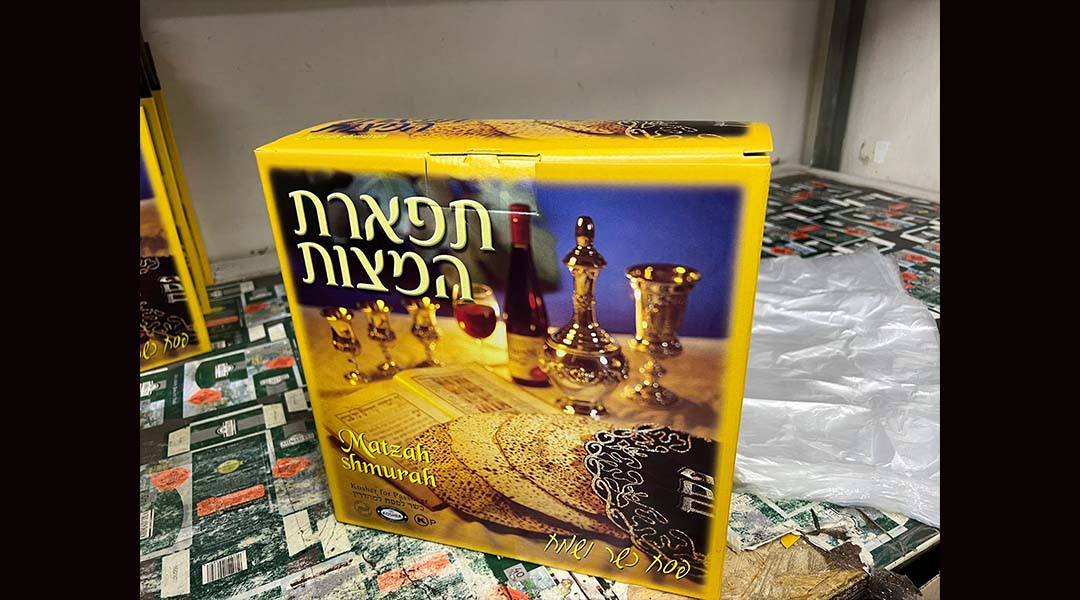

Beginning baking around Hanukkah, the Ukrainian factories supply shmura matzah to Jewish communities in the entire former Soviet world in addition to their customers in the United States, Israel and Western Europe. They are sold in America under the brand names Tiferes and Redemption, among others.

Ukrainian factories supply shmura matzah to Jewish communities in the entire former Soviet world in addition to their customers in the U.S., Israel and Western Europe. (Courtesy of Meyer Stambler)

In Dnipro, the city where Stambler and his main matzah factory are based, periods of pogroms in the 19th century, which sent Eastern European Jews fleeing to the United States, are no longer top of mind for residents. The Holocaust and even Soviet repression also seem to be more distant memories.

Today, Dnipro — known until 2016 as Dnepropretrovsk — is the most Jewish city in Ukraine, boasting the massive Menorah Center, a seven-branched building designed to look like the sacred candelabra and filled with kosher restaurants, wedding halls, ritual baths and other amenities for a Jewish community.

Though he has Israeli and American passports that would allow him to leave, Stambler has stayed behind to support the community, even after getting his family to safety.

“It’s very important to know that we’re staying here because we’re a part of the community, a part of the city.” Stambler said. “Just like President Zelensky said, each person has to fight on his own front. Our front is spreading Yiddishkeit.”

As Russian missiles struck the outskirts of Dnipro earlier this month, dozens still gathered for Shabbat, including many refugees who had come from harder-hit regions.

“We’re helping people from the whole Ukraine,” Stambler said. “From Kharkiv, from Zaporizhia, from Mariupol. We had 70 families who came out of Mariupol.”

Matzah production is still going on in town as well, though Stambler said about two thirds of the factory’s staff had fled. Those who remain are making matzah just for Ukraine.

“We’re going to make a very big campaign to bring the seder to every Jewish home,” Stambler said.

Stambler has plans for the 20,000 pounds in port as well.

“The only way I can bring it back to Ukraine is if it’s for the needs of the army,” he said.

Ukrainian men between 18 and 60 are forbidden from leaving the country in case they are needed for the war effort. Many Jews have already joined volunteer self defense units which are organizing across the country.

If the war stretches until Passover, something that appears increasingly likely as Russia continues to shell areas it had suggested it might Stambler said, there could be many Jewish soldiers looking for matzah in the Ukrainian Army.

Most of it will stay in Ukraine, he said, but a last truck is still scheduled to bring some of the surplus out to the United Kingdom. It will be the last international shipment of Ukrainian matzah this year.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.