(New York Jewish Week via JTA) — David Sipress did not sell his first cartoon to The New Yorker until 1997, when he was 50. He wasn’t exactly a struggling artist until then — his work had long appeared in the Boston Phoenix, Playboy and the Washington Post, and he had some success as a sculptor. But The New Yorker represented the kind of career pinnacle that any good son would want to share with his father — especially a Jewish father who never regarded art as a viable career.

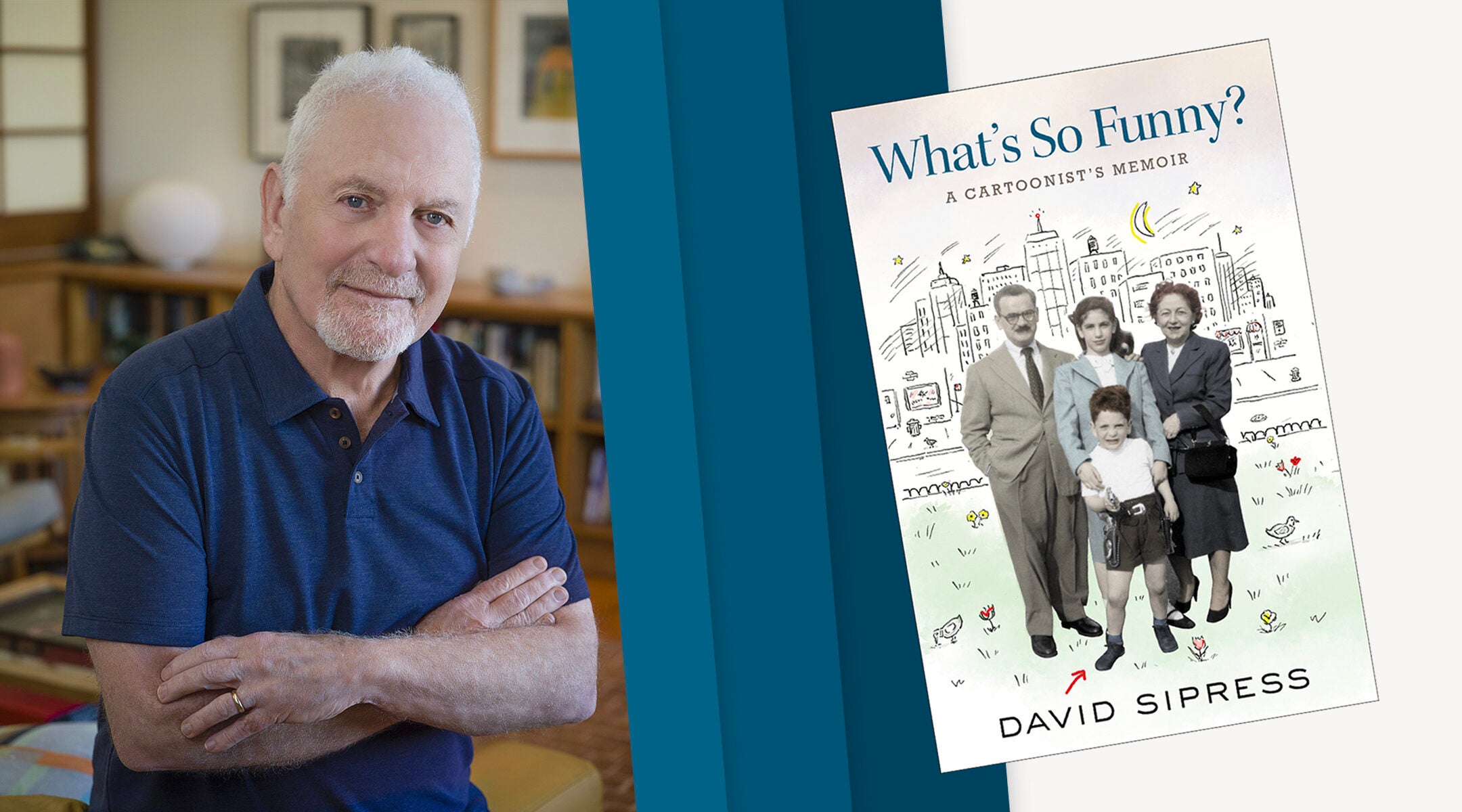

Nat Sipress lived long enough to hear the good news from David, but not long enough to see the cartoon in print — a wry, ironic twist that sounds like, well, a David Sipress cartoon. The cartoonist’s new memoir, “What’s So Funny?” explores the fraught relationship between demanding parents and a son whose dreams didn’t match up with theirs.

The book is also a portrait of New York City in the 1950s and ’60s. Sipress grew up on West 79th Street, attended Horace Mann High School, and spent summers with his family on the beach in Neponsit, Queens. Nat Sipress, who immigrated from Ukraine as a child, ran a high-end jewelry store on 61st Street and Lexington Avenue. David’s mother, Estelle, devoted her days to making sure her husband had nothing to worry about outside of his business. “Like many Upper West Side Reform Jewish families in the 1950s,” Sipress writes, the family celebrated both Hanukkah and Christmas, singing what sounded to a young David like “deck the halls with boughs of challah.”

The book is liberally illustrated with cartoons, including one that could serve as the Sipress family crest: A father tells his grown son, “I never said I was proud of you because I didn’t want you to get a swelled head.”

David Sipress fielded The New York Jewish Week’s four questions about the process of writing so emotional a memoir and his deep connection with his native New York.

1. I was presumptuously expecting your book to join the long list of the “backstage at The New Yorker” memoirs, but it is really an exploration of how your parents — especially your dad — shaped your sense of humor and sense of self. Is that the book you originally set out to write?

Sipress: I wrote “What’s So Funny?” out of a longstanding desire to get down on paper the family stories that have been rattling around in my head for as long as I can remember. Every time I sat down to write, my mother, father and sister were there, demanding to be written about. I’ve spent much of my life obsessing about their secrets and why I knew so little about them, making cartoons about them, discussing them in therapy, thinking about all the ways they shaped who I am — my worrying, my ambitions, my sense of humor and much more — in spite of the physical and emotional distance between us. So yes, that was the book I intended to write.

Of course, there were unexpected pathways that opened up along the way. It quickly became clear to me that I couldn’t tell my family stories without also writing about my creative process and my career as a cartoonist. As I say in the book, “the border between my life and my work is flimsy at best.”

And I’ve always been interested in the prospect of combining autobiography and cartoons, but it was only when I had finished my first draft that I came to realize that including my cartoons could add insight, and more importantly, a salutary dash of humor, to whatever story I was telling. Like nearly everyone, my family story has not always been a happy one. When I started writing the book, I worried about how to write about painful, even devastating, experiences without sacrificing the overall tone of the book, a tone that mirrors who I am — an artist for whom humor is the most natural form of expression. Incorporating the cartoons was key to my solving that dilemma.

(Courtesy David Sipress/Mariner Books)

2. Your book is so exacting in excavating the details of a specific New York Jewish life. (I am thinking of what you wrote about your father and Sandy Koufax: “A strictly secular Jew in the religion department, [my father] became a strictly observant one in the baseball department.”) How did growing up in New York shape your worldview, and might you have been a different person or artist if you had grown up in, say, the suburbs?

The first cartoon in the book depicts a father and his kids strolling in Central Park. The sun is peeking out behind the tall apartment buildings on Central Park West. The father explains, “The sun rises in the Upper East Side and sets on the Upper West Side.” I think that sums up my New York-centric world view. Growing up here always made me feel special, and the city has been an inspiration for me my whole life, filling me with a sense of possibility as an artist, constantly sparking ideas for cartoons and for my writing. One of the pleasures of writing “What’s So Funny?” has been exploring my memories of the city that I love and recalling the different ways I’ve experienced it at different times in my life. I cannot imagine having grown up anywhere else.

3. You describe the generation gap between you — born here, relatively affluent, protected from suffering — and your father, whose journey you describe as one “from impoverished immigrant with a fifth-grade education to successful businessman.” For any kid who dreams of being an artist — and risks disappointing their parents — what advice do you have?

I always hesitate to give advice to anyone about the big choices in life. Everyone’s path is different. I only know that for me, as I say in the book, not defying my parents and turning my back on my dream of being an artist would have meant being “trapped in the wrong life.” I guess I would say to that kid who shares my dream, if you feel as strongly as I did, you really need to listen to that.

“You’re quitting school? After everything we sacrificed for you?” (Courtesy David Sipress/Mariner Books)

4. I love the story you tell about how one of your drawings — a guy at a bar, with the word “BAR” in the window spelled backward — sat around forever until you hit upon the right caption. I know “Where do you get your ideas?” is a confounding question, but what do you tell other budding cartoonists or creators about finding inspiration?

I only ever talk about my own process. My ideas come chiefly from paying attention to what I’m experiencing day-to-day, noting what people say and how they say it, thinking about what makes me happy, what scares me, what makes me angry, always keeping a part of my brain actively on guard for cartoon ideas, never giving up on an idea as with the cartoon you reference. If writing my memoir has shown me anything, it’s that there have been very few things I’ve experienced that I haven’t made a cartoon about at some point. So, when I’m asked, “Where do you get your ideas?” I can honestly reply, “Everywhere. All the time.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.