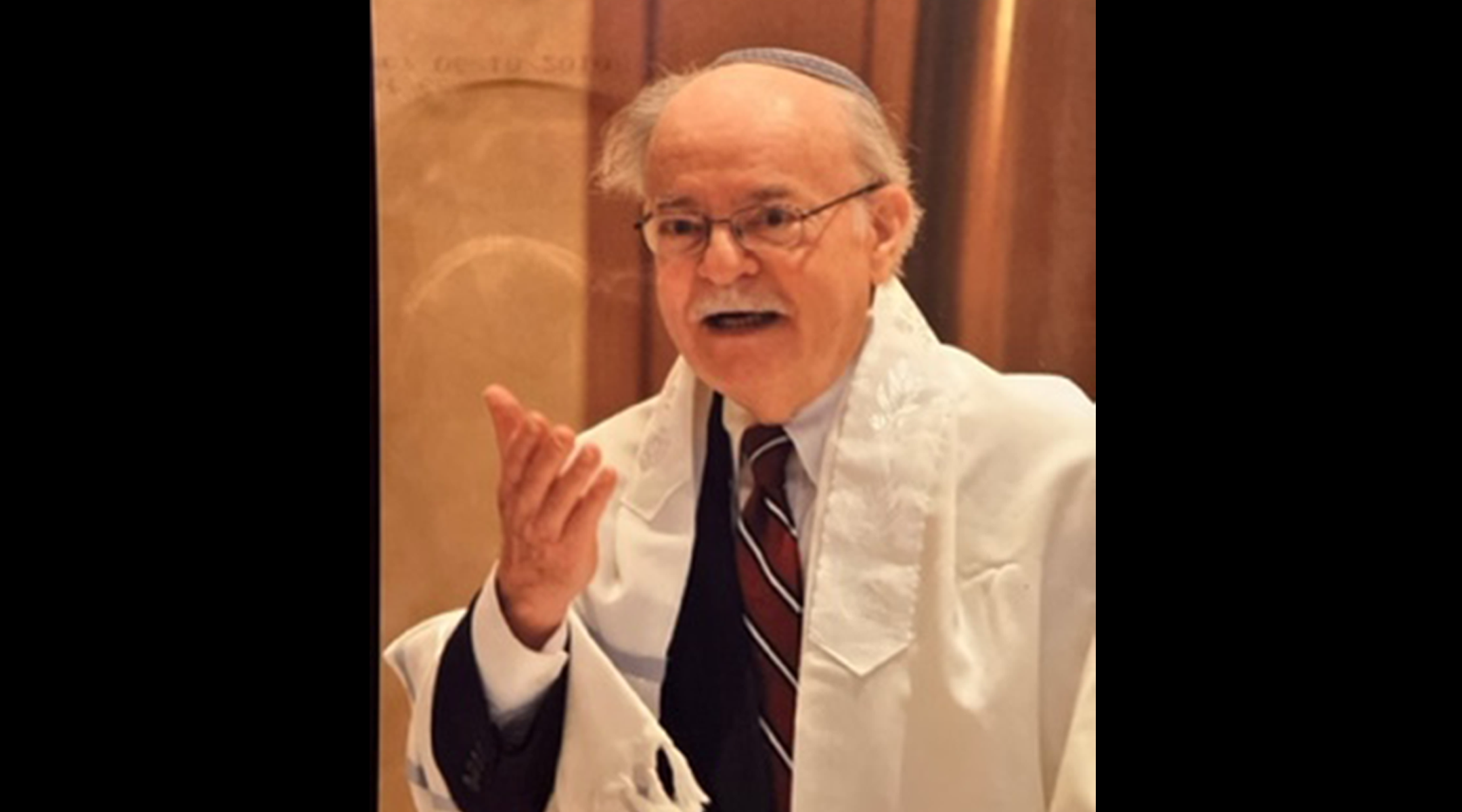

(Philadelphia Jewish Exponent via JTA) – Rabbi Simeon “Shim” Maslin, a national leader in the Reform movement who pushed Reform Jews to embrace lifecycle traditions and a more substantive interpretation of mitzvah, died from cancer on Jan. 29. He was 90.

Maslin was the senior rabbi at Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, for 17 years, from 1980 to 1997 – his last stop in a 50-plus-year career that included positions in Chicago, Curaçao and Monroe, New York. He also served as president of the Central Conference of American Rabbis, an organization uniting about 2,000 Reform rabbis.

As a Reform leader, Maslin wrote the book “Gates of Mitzvah” in 1979, which, according to current KI Rabbi Lance Sussman, introduced classic Jewish life cycle practices into the Reform movement.

“We Jews have not survived for 4,000 years in order to leave to the world a legacy of lox and bagels, nor in order to leave a legacy of ethnic comedy and best-selling fiction, not even to leave a legacy of Nobel Prize winners,” Maslin wrote in the book, explaining why he endeavored for Judaism’s most liberal denomination to better understand and appreciate religious tradition.

Before “Gates of Mitzvah,” the movement focused less on ritual than on its platform of the moment, Sussman explained. It would hold conventions to codify values like the affirmation of a belief in God or Zionism. Maslin’s insight helped modern Jews go deeper and conduct baby namings, marriages and funerals in an authentic fashion.

“He played that role of reintroducing tradition into Reform Judaism,” Sussman said.

The book was so influential that Sussman had read it before he’d even met the leader of the congregation he would one day lead.

Reform Judaism is about navigating cultural change and keeping the religion relevant to each new generation. For most of the movement’s history, starting in the 1800s, its leaders succeeded.

At a Pittsburgh convention in the 1880s, leaders affirmed the concept of God, rejected the kosher laws and described the Jewish experience as religious, not national or ethnic. During a Columbus, Ohio, gathering in the 1930s, leaders moved in the direction of Zionism and the idea of Jewish peoplehood.

Then in the 1970s, they supported the Civil Rights Movement while resisting the Vietnam War. But after that, the Reform movement fell into a malaise, according to Sussman.

“We’re not marching in the streets now,” he said, paraphrasing the prevailing ethos. “Where am I going to go?”

It was Maslin who provided the answer in “Gates of Mitzvah”: Focus on the timeless traditions that make up a Jewish life. The book was the first official CCAR publication to expound on the idea of mitzvah — commanded ritual and ethical behaviors — in Reform Judaism, according to Maslin protege Jeffrey Salkin, rabbi at Temple Israel in West Palm Beach, Florida. In a written remembrance Salkin credited his mentor for introducing the concept of mitzvah to the movement in the 1970s.

“In those days, for many Reform Jews, the word mitzvah usually only followed the word bar or bat,” Salkin wrote in Religion News Service.

Salkin recalled how he and Maslin had once chanced upon Jewish author Philip Roth in a grocery store. After they identified themselves as rabbis, Salkin recalled, Roth immediately fled the store.

Maslin was a proponent of other innovative ideas within the Reform movement, including interfaith hospitality. “I’ve had Christians ask me many times, ‘Can I go to a Jewish service?’ Of course they can,” the Philadelphia Inquirer quoted him as saying. “There’s no secret cult here. Everyone is welcome.”

Born in 1931 in Winthrop, Massachusetts, near Boston, Maslin graduated from Harvard University. He was ordained in 1957 at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, and would often volunteer as a chaplain on cruise ships so he could travel and meet Jews all over the world, according to the Inquirer.

Maslin described himself as a “religious naturalist.” In a 1997 piece for the Inquirer, he wrote: “The function of a Jew is to be co-creator, with God, of the world. The task of the human being is to perfect the world, using the tools God gives us.”

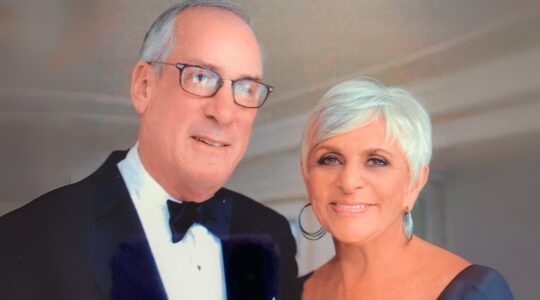

Through his travels, he stayed close to his hometown, vacationing in Maine with his family. He loved boating, fishing, the Boston Red Sox and going on long Sunday drives. As a retiree, he conducted High Holiday services at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine.

But what he perhaps loved most was spending time with his grandchildren. During her eulogy at Maslin’s funeral, Galia Godel, Maslin’s granddaughter, said “he made each of us feel special.”

Godel talked fondly of spending Maine mornings with him at the Bookland Cafe … eating lox on bagels.

A version of this story was first published in the Philadelphia Jewish Exponent and is reprinted with permission.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.