(JTA) — I was born in Kyiv. I shy away from calling myself Ukrainian because at the time it was the USSR. And as Jews who eventually fled as refugees, my family didn’t have any ethnonational attachments to the place. Still, it’s where I learned to sort of smile.

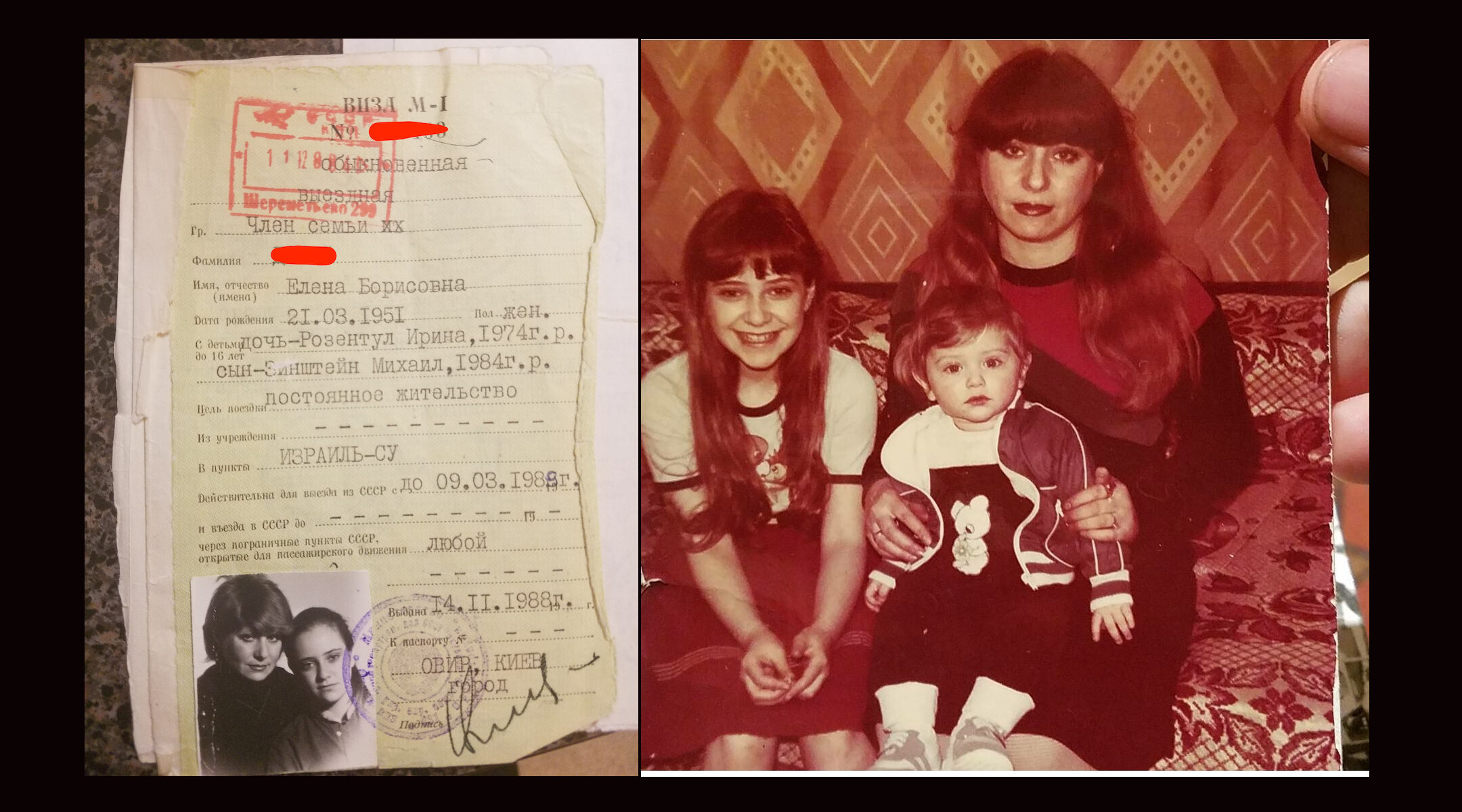

It’s where my favorite photo of my mom and me was taken, just three years before cancer killed her. I remember the large city park by our apartment and its train for tots in the summer. I remember begging my sister to pull me on a sled in winter despite there being little snow.

That I had been born there at all was a function of knowing when to leave — and when to come back. My babushka, my grandmother, fled Kyiv the day before the Nazis came in 1941. Her own grandparents stayed. They were murdered at Babyn Yar.

After the war, the antisemitism in Ukraine under the Soviets was intense and repugnant. My father remembers seeing KGB officers snapping photos of men lined up by the synagogue to purchase matzah for Passover — a crime of Jewish expression.

Men identified in those photos would be fired from their jobs or worse, my dad and his close relatives would recall years later as we sat in our new home in the United States around a dining room table spread with homemade gefilte fish, salat olivier and chopped herring salad. A mention of a pogrom, the killing of Jewish doctors or total Soviet amnesia that Jews were specifically targeted by the millions in Germany’s invasion of the USSR — all of these would get a knowing and exhausted nod.

And so we left again.

I still have all the papers that tell our departure story, familiar to so many Jews who left in the 1980s. Our exit visa to Israel. Our United States refugee papers. Our refugee ID numbers.

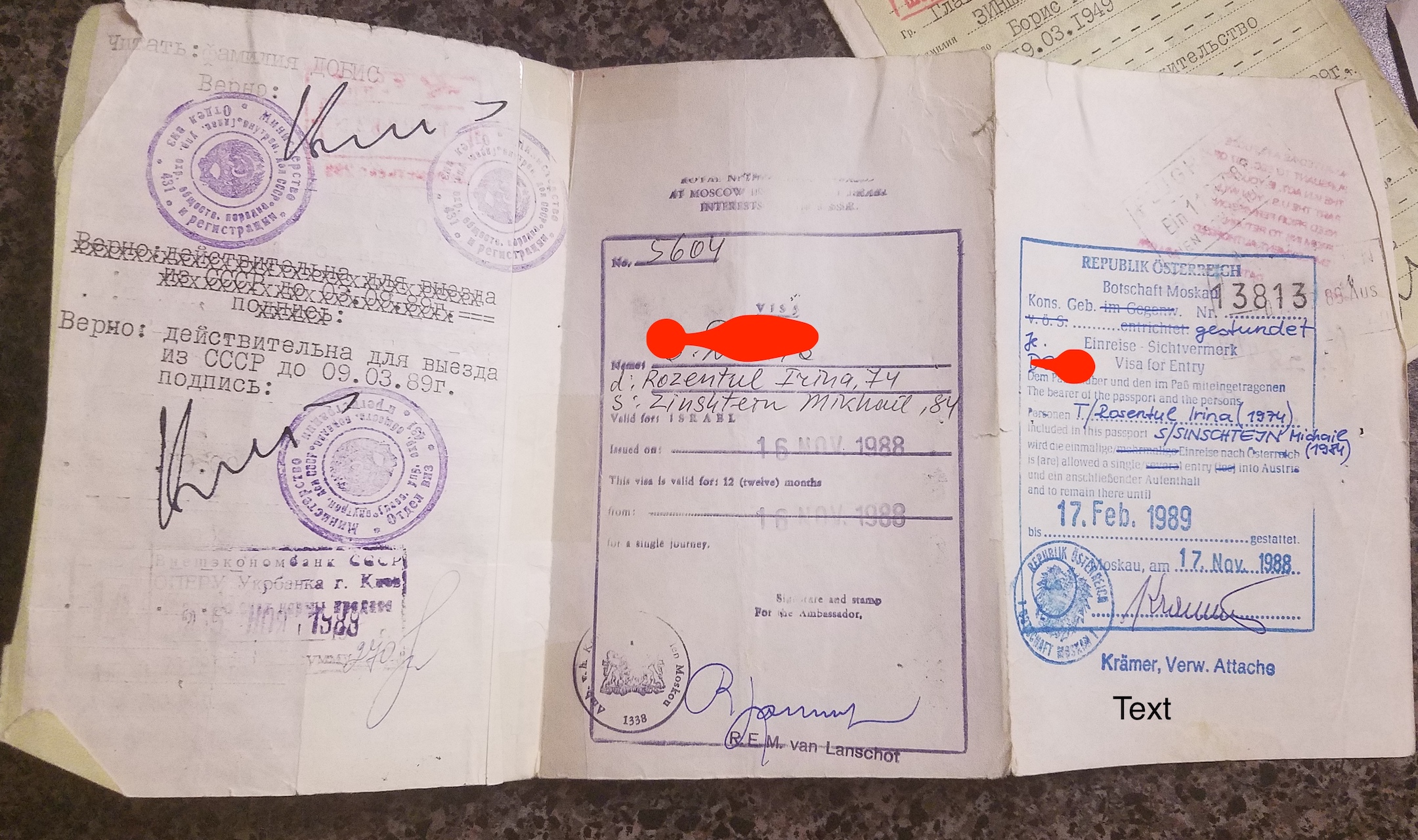

Leaving for Israel, with an official exit visa, was the only way for Jews to get out the USSR. But because Israel and Moscow had no diplomatic ties, all Jews first flew to Vienna.

Three countries contributed to the Zinshteyn family’s visas in Vienna, after they left Kyiv in 1988. (Courtesy Zinshteyn)

While other families bound for Israel pivoted straight to their flights to Tel Aviv, we remained in Vienna waiting for our permission to enter the U.S. Our tri-national spread of exit and entry visas are stamped by the Dutch (Israel’s representatives in Moscow), the Austrians and the Soviets. After several months in Vienna, the Hebrew International Aid Society secured our flight to New York City.

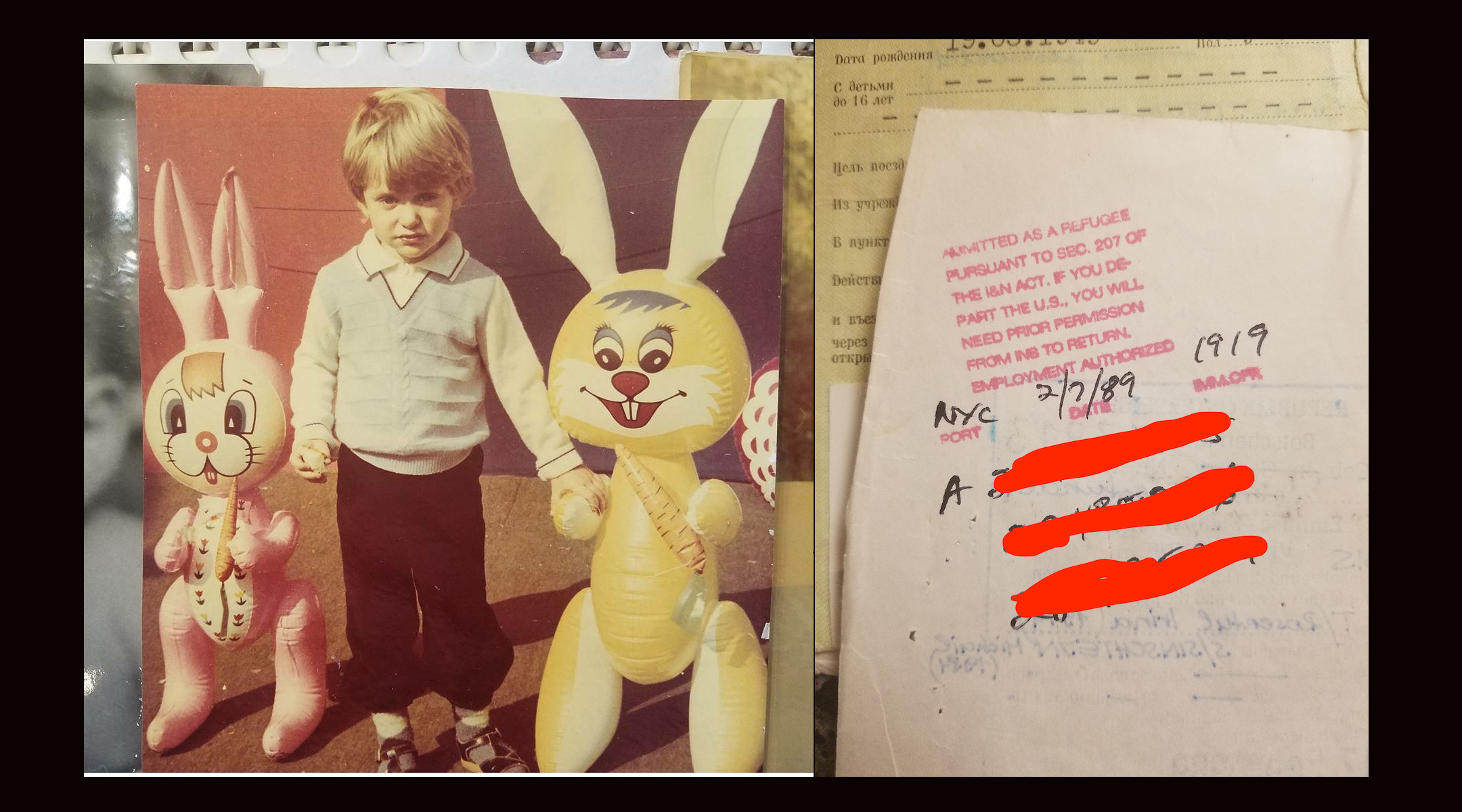

We arrived in the United States as refugees on Feb. 7, 1989. My mom died of an aggressive breast cancer months after our arrival in New York. My family long suspected her cancer was fueled by our proximity to Chernobyl when its nuclear reactor blew. That assumption is scientifically unfounded but played a huge role in my family’s story.

Because I was a child in Kyiv when Chernobyl’s core melted and spewed radioactive waste into the sky, my dad feared I was contaminated, too. For my entire childhood, he’d limit my play outside to when the sun was setting and have me in long sleeves and a hat if we were out in the day — so strong was his fear that the sun could trigger something in me unknown to doctors that Chernobyl left behind. I’d like to think that’s why I’m so pale today.

We first lived in Midtown Manhattan for a few weeks, in what I believe was a halfway home for recovering addicts (the last time I checked, in the 2000s, it was a hotel). My dad recalls speaking to doctors in a hallway payphone about my mom’s worsening state, his broken English competing for clarity over the commotion in the public space. Once in Brooklyn, I attended a Jewish camp with my older sister — experiences organized for us by a rabbi my dad befriended, in part to distract us from our mom’s demise. Months later, we’d move to Los Angeles, where I remained for most of my life and now live again. According to my dad and a photo I once took on a return visit, our old neighborhood was festooned with placards that read “patrolled by private police” — an alleged reference to the organized crime figures who kept watch.

Mikhail Zinshteyn, seen as a child in Kyiv, alongside paperwork from his family’s admission to the United States as refugees in 1989. (Courtesy Zinshteyn)

Despite the trauma of this journey, I regard Kyiv with fondness. My heart breaks for the other children at risk of displacement, the families who may have to flee because of Moscow’s misdeeds.

I didn’t think Putin would commit to a full-scale invasion, that he’d instead try to destabilize Ukrainian democracy with less force. I had also assumed that, considering both lands are united by the horror of Hitler’s invasion, a Russian blitzkrieg of Ukraine would be beyond the pale. Alas.

I quiver that a city that has endured genocidal occupation, nuclear fallout and civil unrest all in the past 80 years must now endure this.

It’s not my place to offer solutions. It is my place to say a city’s tragedy 6,000 miles away feels very present and raw.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.