(New York Jewish Week via JTA) — The glass ceiling of rabbinical ordination was broken at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in Cincinnatti in 1972 when Rabbi Sally J. Priesand became America’s first female rabbi.

Fifty years later, HUC’s New York City branch is celebrating the milestone with an exhibit at its Dr. Bernard Heller Museum. The exhibition, called “Holy Sparks,” pairs 24 female rabbis — all “firsts” of some kind — with 24 female Jewish artists asked to portray their stories.

A collaboration between HUC and The Braid (formerly Jewish Women’s Theatre), a Santa Monica, Calif.-based Jewish theater company, “Holy Sparks” reflects upon the radical and essential shifts in Judaism over the past five decades through the inclusion and rising profile of female rabbis.

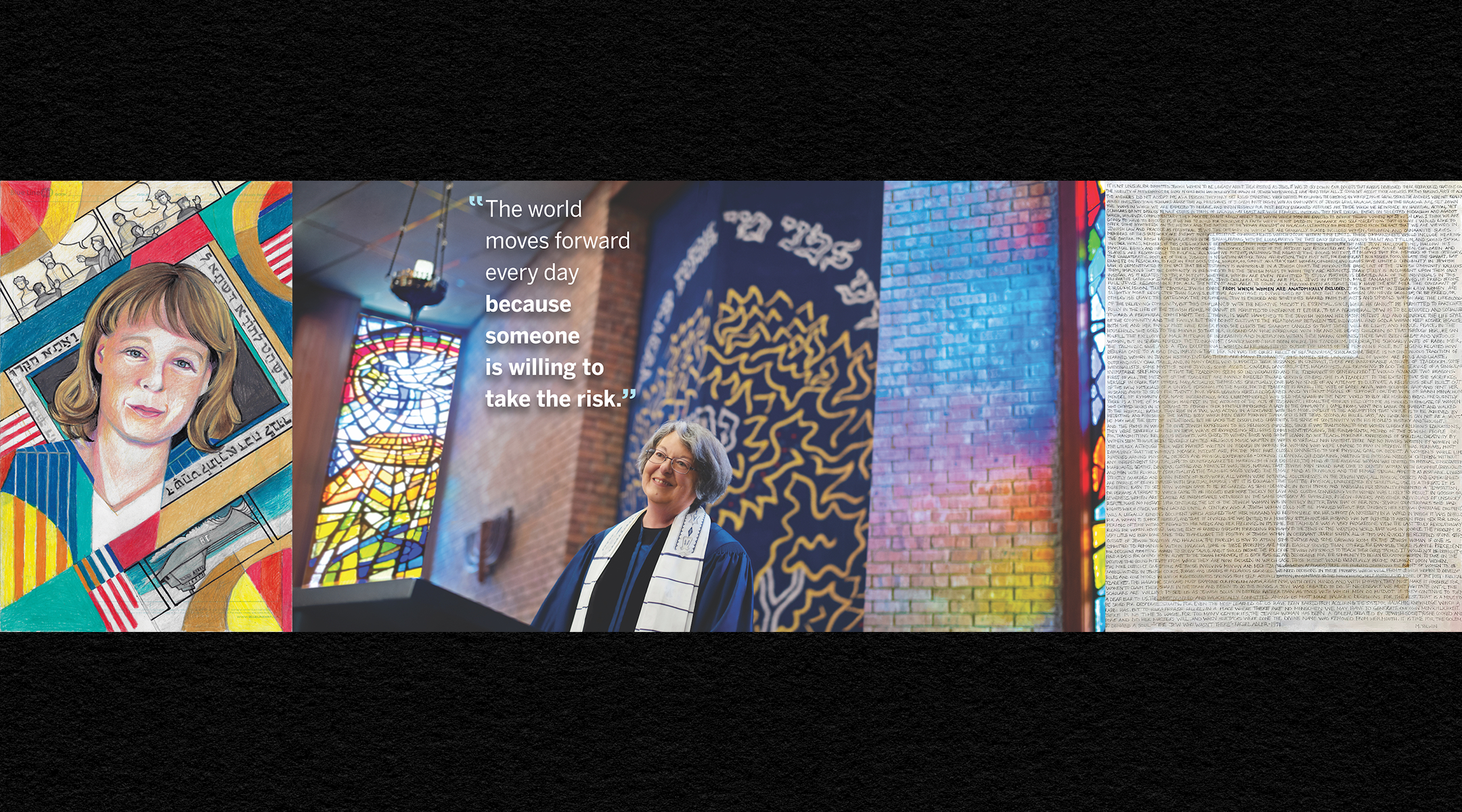

The artworks — which span a variety of mediums and aesthetics, including photography and mixed-media collage — work as the jeweled tiles of a larger mosaic, portraying the women’s often-difficult journey to the rabbinate, along with their tireless work to build a better Judaism.

Some of the included artists had long, close friendships with their rabbis; others referenced transcripts and videos provided by The Braid. The artists only had to follow one rule: keep their pieces within the dimensions of 24”x 30” for easy transport. With its next stop at the Skirball Museum in Cincinnati, “Holy Sparks” is intended as a traveling exhibit, to share the story of these inspirational women internationally.

For Jean Bloch Rosensaft, director of Heller Museum — located at HUC’s campus in Greenwich Village — the exhibition represents the culmination of a three-year project. The museum was initially approached by the leaders of The Braid to transform “The Story Archive of Women Rabbis,” a filmed collection of 200 interviews, into works of original art by contemporary women artists.

Rosensaft and her curatorial team had the difficult task of winnowing down the profiles to a manageable number; they then arranged the 24 “pairings” of artists and subjects. Artists were intentionally chosen with diverse aesthetics, including Debra Band, who is known for intricate paper cuttings, and Judy Sirota Rosenthal, who is known for mixed media installations. The result, according to Rosensaft, is one of “unity without uniformity.”

“‘Holy Sparks’ shares our deep sense of appreciation and gratitude to women in the rabbinate, for the journey they have taken and struggles [they] confronted,” she told The New York Jewish Week.

Photographer Joan Roth captures Priesand with a subdued photograph that is overlaid with a famous quote from the rabbi: “The world moves forward every day because someone is willing to take the risk.” In the photo, Priesand simply stands on the bimah, the raised stage at the front of a synagogue, as a trickle of rainbow light plays on the wall next to her. The picture exudes a quiet power: She is right where she belongs.

The exhibit then progresses chronologically by ordination year. Featured rabbis include Rabbi Kinneret Shiryon (ordained in 1981), the first woman to serve as a community rabbi in Israel, and Rabbi Denise L. Eger (1988), the first gay person to serve as president of the Central Conference of American Rabbis. “The order is intended to manifest how each generation and decade of women rabbis have built on the previous decade,” Rosensaft said.

What’s striking about the pieces in “Holy Sparks” is how well they work together, despite the wide range of materials and styles. They all grapple with the intersections of Judaism and feminism, and many highlight art forms that were, for centuries, considered simply “women’s work,” such as embroidery and weaving. Each individual piece reflects on crucial elements of a rabbi’s essence: her being, her words, her tradition, her actions, her devotion to her community.

The process could be difficult at times. Painter Marilee Tolwin, for example, struggled to encompass the essence of Rabbi Rachel Adler — one of the first ethicists to interpret Jewish texts through a feminist lens — on a mere 24” x 30” canvas. Her piece evokes both Agnes Martin’s modernist grid paintings and micrography, a Jewish form of calligraphy where quotations written in tiny Hebrew letters are used to create designs. Tolwin copied Adler’s entire landmark feminist essay, “The Jew Who Wasn’t There,” in miniature and overlaid it with the structure of a Talmud page.

“I stood back and saw which sentence had fallen in the center: ‘From which women are anatomically excluded,’” Tolwin said. “It was bashert [destiny], the essence of Rabbi Adler’s life work.”

For Emily Bowen Cohen, the Jewish and Native American cartoonist behind the mini-comic “An American Indian Guide to the Day of Atonement,” working on a single canvas for her painting, “Rabbi Julie” — about Julie S. Schwartz, the first woman rabbi to serve on active duty as a chaplain in the U.S. military — meant departing from her medium entirely. “Working on this portrait challenged me to communicate a whole story on just one page,” she said.

Her solution: twist an entire book of comic panels behind the portrait of the rabbi. Schwartz had to juggle the regimented image of a naval chaplain with her radical role as first woman rabbi serving on active duty. Inspired by the aesthetic of naval advertisements from the 1940s, “Rabbi Julie” evokes a Jewish Rosie the Riveter, optimistic and bursting out from the traditional framework patterned behind her.

As with many ventures touting diversity of representation, there are notable omissions. There are no pieces dedicated to Rabbi Lauren Tuchman, the first blind woman rabbi; Rabbi Sandra Lawson, one of the first openly queer, Black rabbis and the inaugural director of Racial Diversity, Equity and Inclusion for the Reconstructionist movement, or Rabbi Emily Aviva Kapor, the first trans woman rabbi.

With any luck and wisdom, we won’t have to wait until the 100th anniversary of women’s ordination to celebrate these trailblazers. As Rosensaft writes about the 24 women rabbis chosen for the exhibit, “May these builders of a vital Jewish future go from strength to strength.”

“Holy Sparks: Celebrating 50 Years of Women in the Rabbinate” is on view at the Dr. Bernard Heller Museum, 1 West 4th St., New York, from Feb. 1 through May 22.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.