(JTA) — What really happened near a beach in Israel in 1948?

The question, once debated in a 20-year-old libel suit that served as a microcosm for the battle over Israel’s historical record, reentered the public consciousness this week. Entities including the Palestinian Authority and the editorial board of Haaretz have begun calling for a commission to excavate land near Mount Carmel in search of an alleged mass grave site in which perhaps 300 Palestinians may be buried.

The renewed attention is due to an explosive new documentary, “Tantura,” directed by Israeli filmmaker Alon Schwarz, which premiered virtually Jan. 20 at the Sundance Film Festival. In the film, Schwarz interviews several Israeli veterans who, in the country’s 1948 War of Independence, served in the Alexandroni Brigade, a regiment that forcibly displaced Arab residents of the village of Tantura following the formal conclusion of the war in order to build Dor Beach and the neighboring Kibbutz Nahsholim.

On camera, many of these former soldiers tell a disturbing story: They had participated in a massacre, one the Israeli government subsequently covered up.

“We killed them. No qualms at all,” one of the interviewees says. Another says he “didn’t count” how many unarmed Palestinians he killed, except to note, “I had a machine gun with 250 bullets.” (Various accounts in the film estimate the death toll at between 200 and 300.) A third recounts witnessing a rape.

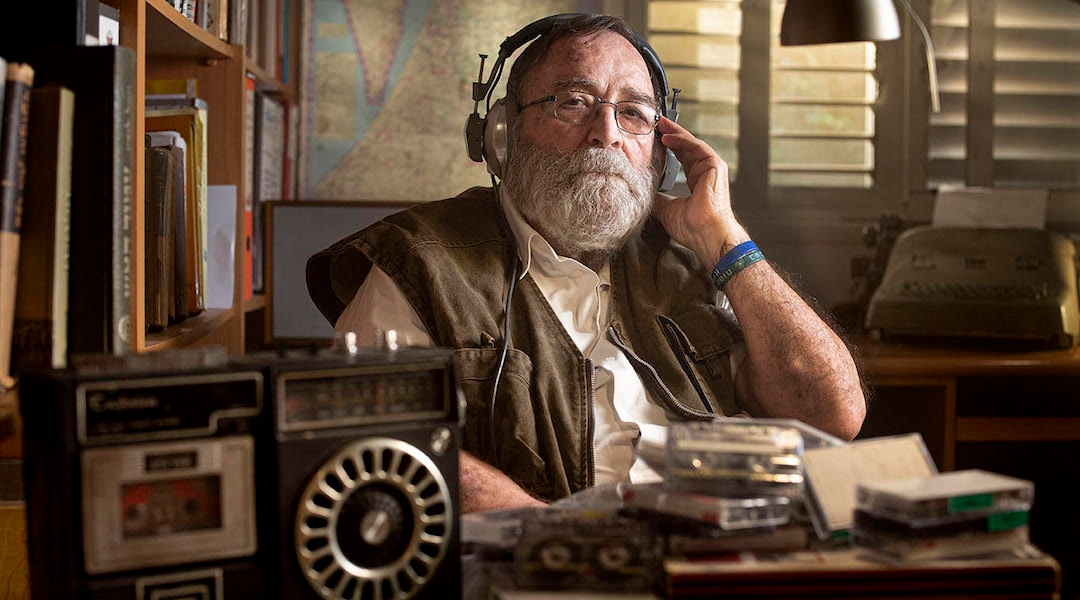

These elderly Israelis, many of them nonagenarians and four of whom have lived on Kibbutz Nahsholim since 1948, had told their stories at least once before: to the film’s protagonist, onetime historian Theodore Katz. In 1998, for his graduate thesis at Haifa University, Katz amassed more than 140 hours of tape interviewing witnesses and survivors of Tantura (half of them Israeli, the other half Arab) to compile an oral history of the events, for which no paper documentation exists or has yet been made public by the Israeli Defense Forces archives.

Two years after Katz submitted his thesis, its claim of a massacre was picked up by Israeli media and ignited a firestorm of controversy. Soon after, many of his interview subjects recanted their testimony and sued Katz for libel. Katz signed an apology recanting his research, only to immediately claim the apology was coerced. The university pulled his thesis from its shelves, and to this day his findings are questioned by the government and some Israeli academics (one of whom, IDF historian Yoav Gelber, criticizes Katz’s sole reliance on oral testimony by remarking in the film, “I don’t believe witnesses”).

“If you want to make a movie of them,” Katz warns Schwarz, referring to the taped testimonies, “be careful, because you’ll be hunted down as I was.”

Alon Schwarz, director of “Tantura.” (Avner Shahaf)

In the film, Katz’s defense attorney says his libel case was the first Israeli trial to deal directly with claims of Israeli war crimes during the 1948 war, known by Palestinians as the “Nakba,” or “catastrophe.”

Tantura joined a small but potent group of allegations of Israeli violence against Palestinians in 1948 that have been hotly debated in Israeli society ever since, including incidents at Deir Yassin and Lydda/Lod. A similar documentary on Deir Yassin, in which Israeli director Neta Shoshani collected eyewitness and archival accounts from soldiers, premiered in 2017.

Prominent Israeli “New Historian” Ilan Pappé, whose work questions large parts of the Zionist historical narrative on 1948 and who had been a major supporter of Katz’s thesis, also becomes a character in the film. A vocal supporter of the “one-state solution” that would combine Israel and the Palestinian Territories into a single unified government, Pappé invokes the term “ethnic cleansing” to describe what took place not only in Tantura but also across the Zionist project as a whole, from 1948 to today.

The film never explores exactly why Katz’s subjects are now suddenly willing to come forward again and verify that their testimonies are true. In his director’s statement, Schwarz theorizes they opened up “as if they wanted to share a truth deep inside their soul.” Whichever the reason, Schwarz’s relitigation of the case, which includes playing Katz’s original audiotapes, produces shocking results. Subjects offer a steady drip-drip of half-remembered firsthand details: soldiers chasing villagers with flamethrowers; a mule-drawn cart carrying corpses to a mass grave.

Schwarz builds his interviews to a finale in which he uses historical mapping software to pinpoint a specific parking lot near the beach. Excavate the lot, the film’s participants essentially dare, and you may find the truth.

That’s exactly what the P.A. and various members of the Israeli left are now calling on Israel to do. Immediately following the film’s Sundance premiere, the groups began to demand that the government investigate the veterans’ claims, dig up the alleged gravesite and erect a memorial to the lost Tantura. The P.A. says an international commission should be formed to further probe the claims in the film.

Whether or not these efforts to resurface claims dating back to Israel’s very founding will prove successful, Schwarz’s film has already generated heated conversation around how the Jewish State commits itself to its own memory. If “Tantura” finds a distributor willing to back its post-Sundance release, that conversation is sure to grow even more intense. As one of the subjects notes, “A state is seized by the sword.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.