(JTA) — As she began to think about what she would tell her congregants on the Shabbat after the hostage crisis at a synagogue in Colleyville, Texas, Rabbi Jennifer Lader of Temple Israel in suburban Detroit realized she had already prepared.

Grotesquely, Colleyville was far from the first time she would face concerned congregants after an assault on a Jewish place of worship. She had done so after the 2018 shooting at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life congregation, in which 11 Jews died, and about the attack on the Chabad of Poway near San Diego.

She also thought of the Charlottesville rally by white supremacists that turned deadly, which which saw neo-Nazis marching past a local synagogue during Shabbat services.

“It’s awful and depressing that I have all these sermons on file ready to go for the next time the tragedy strikes the Jewish community. It’s scary to be Jewish in America these days,” said Lader, who has known Charlie Cytron-Walker, the rabbi taken hostage in Colleyville, for several years.

Lader isn’t alone in considering how to factor Colleyville into her Shabbat experience this week and beyond. Across the country and world, rabbis and those who help them lead their synagogues are weighing a host of concerns: Is their security strong enough? What messages are they seeking to deliver? Will congregants feel safe about joining at all?

The resurgence of the COVID-19 pandemic means that some synagogues have scaled back or eliminated in-person worship. Still, Jews are being encouraged to attend services in person this week as a sign of unity by national figures such as Deborah Lipstadt, President Joe Biden’s nominee for State Department antisemitism envoy.

Recalling the turnout after past attacks, Lader says she doesn’t think the congregants at her synagogue, a Reform congregation with more than 3,100 families, will need much of a push.

“We’ll have more people in person this week than we had last week,” she said. “In moments of trauma, people want to be together, people want to see each other’s eyes and faces, even behind a mask.”

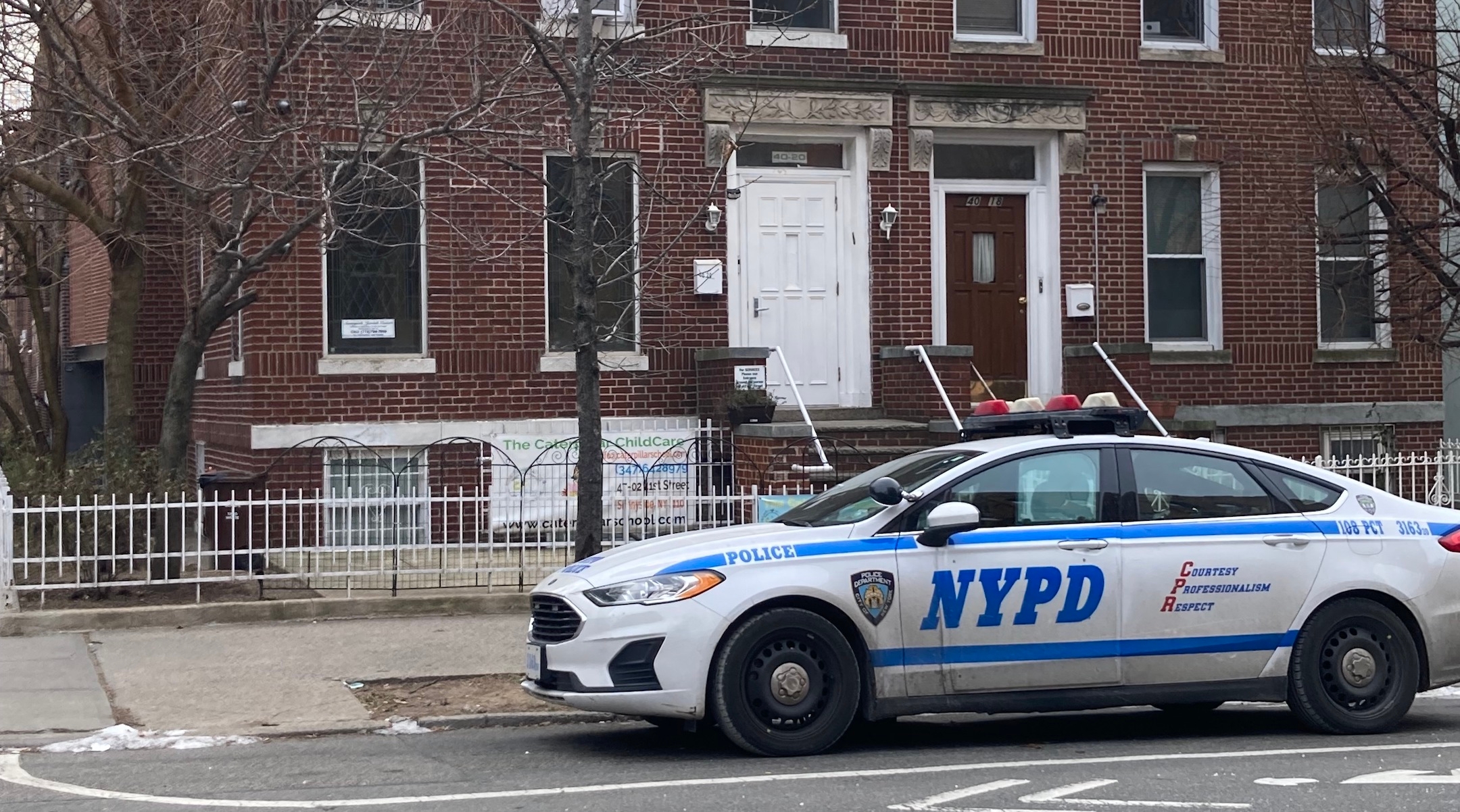

Some of the people who make their way to American synagogues this week will encounter ramped-up security measures, whether they notice them or not. Many local police departments have dispatched extra patrols, and in email chains and masked meetings, synagogue boards and employees have spent the week discussing whether they have taken enough precautions to keep their communities safe.

Many have reached out to the organizations that support Jewish security efforts: Michael Masters, CEO of the Security Community Network, which Cytron-Walker credited with training he used on Saturday, said his group was getting dozens of requests for training daily from American Jewish institutions.

Other communities are confident in the security they already have in place, including Lader’s. Among the largest congregations in the country, it spends roughly a quarter million dollars a year on security, according to Lader.

An NYPD patrol car parked outside the Sunnyside Jewish Center in Queens on Sunday, Jan. 16, 2022. The city deployed additional resources to Jewish locations around the city on Saturday night as the hostage crisis at a Dallas-area synagogue unfolded. (Lisa Keys)

On the opposite end of the spectrum in terms of size is Congregation B’nai Isaac in Aberdeen, South Dakota. The community it serves is so small that the synagogue sometimes fails to make a minyan, or prayer quorum of 10 adults, according to congregant Herschel Premack.

Premack told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency that his community, too, is confident in its precautions, which include security cameras and a door with special locks. He said he doesn’t anticipate any changes after the attack in Colleyville, in part because he doesn’t see his congregation as a target.

“We don’t think that we’re in the same jeopardy as those people down there,” Premack said. “We’re in a small, rural community and we’re not feeling some of the things that they are in the bigger communities.”

In California’s Bay Area, some synagogues are tightening security. Others are planning to move forward as they have been — and expect that their congregants will come along.

“I haven’t heard anything this week, any added concern from anybody,” said Rabbi Eliezer Poupko of Bar Yohai Sephardic Minyan in Silicon Valley, an Orthodox congregation where news of the hostage situation didn’t become known until near its end, because of the Orthodox practice of not using electronic devices on Shabbat and the time difference between California and Texas.

What happened in Colleyville was “extremely disheartening,” Poupko said, but he added that he has not felt it necessary to change the plan for services or to ramp up security beyond the guard hired to show up Saturday mornings. Many of his congregants are from Israel, where security guards are a prominent feature of public life.

“We have not heard any doubts about whether people are going to show up this week,” he said. “We see continued confidence about coming to shul.”

That’s a message that Cytron-Walker himself has tried to advance. He told JTA Wednesday that what happened to him was a rare incident, not a sign of what American Jews should expect each week.

“It’s safe to go to shul,” Cytron-Walker said.

Cytron-Walker also said that he believed it was important for synagogues to continue to be welcoming, even as it was his decision to let a stranger through Congregation Beth Israel’s locked door that led to his being taken hostage.

How to balance the need for security against the value of inclusion is on the mind of many as Shabbat approaches, and with it the potential for people who are not synagogue regulars to show up to services out of solidarity, as happened in 2018 after the Tree of Life shooting.

In the face of uncertainty, Rabbi Paul Kipnes of Congregation Or Ami, a Reform synagogue in suburban Los Angeles, has adopted a new motto that he shares with his staff: “WWRCD.”

“What would Rabbi Charlie Do?” he said. “That’s the gold standard.”

CORRECTION: This article previously said, in paragraph 11, that Temple Israel spends roughly half a million dollars a year on security. After publication, the synagogue updated JTA to say the true figure is closer to $250,000.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.