(New York Jewish Week via JTA) — Now in its 31st year, the New York Jewish Film Festival, the annual cinematic celebration of Jews from around the world, kicks off on Wednesday. Its organizers are determined to stage the event, even amid the spread of the omicron variant.

This year’s festival runs from Jan. 12 through Jan. 25, and is co-presented by New York’s Jewish Museum and Film at Lincoln Center. Narrative films, shorts and documentaries are all in the program, as well as one of the last onscreen performances by Jewish actor Ed Asner. In acknowledgment of the pandemic, the festival will offer a mix of both in-person and virtual screenings. (Lincoln Center requires proof of full vaccination for all in-person film screenings.)

Which films should you check out? Here are some highlights from this year’s program, compiled by the New York Jewish Week.

A still from “Neighbours,” the opening-night film of the 31st New York Jewish Film Festival at Lincoln Center. (Menemsha Films)

“Neighbours” (Opening film: Jan. 12, in-person)

The year is 1980, and an intrepid young storyteller, Sero, lives with his Kurdish family on the Syrian/Turkish border. With a 6-year-old’s curiosity and naivete, Sero experiences the tumultuous changes happening in his region through small, life-changing events, including the death of his mother and the arrival of a new teacher whose curriculum mainly consists of antisemitism and Syrian nationalism. These new lessons seem to conflict with Sero’s neighbors, the last Jews in the village — they love and take care of him as if they were his own family. Sero must reconcile the intense antisemitic tropes he is learning in school with the love and comfort he has felt from his Jewish neighbors his whole life. With dialogue in Kurdish, Arabic and Hebrew, “Neighbours” stages complicated historical events in a way that is both heartbreaking and revealing — only children are still able to move through the world without fully understanding it, able to see who is kind and who is harsh. A Q&A with director Mano Khalil will follow the screening. — Julia Gergely

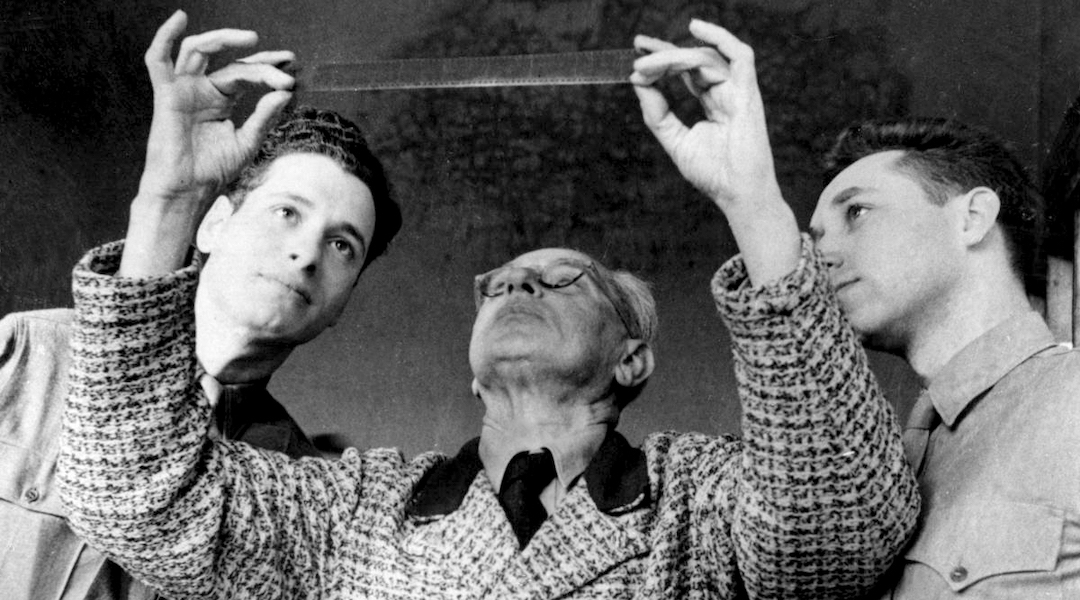

“The Lost Film of Nuremberg” (Courtesy of the Jewish Museum)

“The Lost Film of Nuremberg” (U.S. premiere: two screenings on Jan. 13, in-person)

In 1945, immediately after the war in Europe ended, brothers Stuart and Budd Schulberg were dispatched by American intelligence to collect film and photographic evidence against the Nazis to be used in the upcoming war crimes trial at Nuremberg. “The Lost Film of Nuremberg” retraces their efforts, and chronicles how the celluloid they amassed has shaped our understanding of the Holocaust ever since. But the film also tells a more complicated story about how Justice Robert Jackson, the chief U.S. prosecutor, assigned Stuart Schulberg the task of filming the trial itself — an idealistic project undermined by Cold War cynicism. Shifting alliances meant Stuart Schulberg’s film largely sat on a shelf for some 70 years, until restored by his daughter, Sandra. Combining vintage film clips that still shock with interviews with present-day scholars, the documentary poses questions about the ultimate lessons of World War II and whether they are being heard today. Q&As with director Jean-Christophe Klotz and producer Sandra Schulberg will follow the screenings. — Andrew Silow-Carroll

“Sin La Habana” (Courtesy of the Jewish Museum)

“Sin La Habana” (Centerpiece film: Jan. 15 and 17, in-person)

In this lovely drama of displacement, professional ballet dancer Leonardo (played by real-life ballet dancer Yonah Acosta) devises a plan to escape Cuba with his lawyer girlfriend, Sara, by tricking an Iranian-Jewish tourist (Aki Yaghoubi) into paying for exit papers so the couple can start a new life in Montreal. Religious and cultural rites are spliced delicately through the movie as all three parties angle for their own outcomes. A beautiful film that is both artistic and raw, told in English, Spanish and Farsi, “Sin La Habana” is a nuanced exploration of the impacts of migration and resettlement. Q&As with director Kaveh Nabatian, who also composed the film’s music, will follow the screenings. — Julia Gergely

“The Will to See” (Marc Roussel)

“The Will to See” (Jan. 16, in-person)

French Jewish public intellectual Bernard-Henri Lévy delivers his latest politically charged report from the world’s conflict zones in this documentary, a companion to his latest book of the same name. Lévy and co-director Marc Roussel visit sites of massacres in Nigeria; refugee camps in Greece; training bases for anti-fundamentalist rebel factions in Afghanistan and the Kurdistan region and more. (A longtime Israel supporter, Lévy pointedly refuses an editor’s suggestion to file a report from Gaza.) Lévy has been making these kinds of journeys for decades in an effort to galvanize the Western world’s sympathy. He also rails against France’s strict COVID-19 lockdowns, declaring that “Europe retreats behind barricades” rather than face the world’s problems head on. In one fascinating scene, he meets the detained children of people who have joined ISIS and introduces himself as a Jew, saying that, to him, all religions are brothers. A Q&A with Lévy will follow the screening. — Andrew Lapin

“A Kaddish For Bernie Madoff” (courtesy of the filmmakers)

“A Kaddish for Bernie Madoff” (Jan. 17, in-person)

When financial fraudster Bernie Madoff was arrested for perpetuating the largest Ponzi scheme in history, Madoff’s Jewishness — and the Jewishness of many of his victims — struck Jewish writer and musician Alicia Jo Rabins. After Rabins’ mom told her that the Mourner’s Kaddish had been recited for Madoff at a synagogue where many of his investors/victims were members, her obsession with Madoff grew into a drive to speak to his victims. This experimental feature, made prior to Madoff’s death in April 2021, finds Rabins and director Alicia J. Rose modernizing an ancient Jewish excommunication tradition: They say a kaddish for Madoff while he’s alive. A Q&A with Rabins, Rose and producer Lara Cuddy will follow the screening. (Read an extended interview with Rabins here.) – Chloe Sarbib

“Shtetlers” (Courtesy of the Jewish Museum)

“Shtetlers” (virtual)

A massive wave of immigration, followed by the atrocities of the Holocaust, meant that the Jewish communities of Eastern Europe’s shtetls had essentially disappeared by the mid-20th century. But, fascinatingly, some Jewish shtetls in Ukraine and Moldova survived until the 1970s — and a few even remained up until the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. An intriguing documentary by Katya Ustinova, “Shtetlers” paints a picture of what life was like in these forgotten Jewish towns, as told through the eyes of nine people who lived in them. The film explores a history that is both revelatory and tragic. Ultimately, Ustinova shows that shtetls were a place of deep culture and of “neighborship,” as she calls it. (Read an extended interview with Ustinova here.) — Maddy Albert

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.