(New York Jewish Week via JTA) — The Holocaust all but destroyed a centuries-old Jewish civilization, while the war carved up nations and left the Continent divided between the allied West and the Soviet-dominated East. The casualties of this upheaval included a monumental collection of scholarship and artifacts telling the story of Yiddish culture.

Before World War II, the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, founded in Vilna (now Vilnius), Lithuania, collected millions of documents and hundreds of thousands of rare books. The Nazis, not satisfied with their war on Jewish bodies, also plundered their past, stealing documents for a planned museum of the vanquished Jewish race in Frankfurt and condemning the rest to destruction.

But much of the Frankfurt material survived. After the war, it was returned to YIVO and ended up at its new headquarters in New York City, thanks to the “Monuments Men,” the U.S. army unit sent to recover artwork and scholarship stolen by the Nazis. Meanwhile, Jews who were tasked with sorting the collections under Nazi orders in the Vilna Ghetto — the famed “Paper Brigade” — managed to hide a trove of materials. That tranche would again be threatened when the Soviets took over Lithuania, and only survived thanks to a Lithuanian librarian who managed to hide the material in church basement.

Like a family divided by the war, the collections found homes in two countries — Lithuania and the U.S. And like a child in a divorce, the Lithuanian trove was subject to a lengthy custody battle between YIVO and the Lithuanian government. The dispute was resolved amicably only in 2014, with a solution made possible only by modern technology: the digitization of all the millions of materials, uniting them online if not under the same roof.

This month marks the completion of the historic project, the Edward Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections, named for its lead donor. Professional and amateur researchers are able to access the entirety of the YIVO archive of 4 million documents, which are in Yiddish as well as dozens of other languages. The materials reflect the religious and cultural diversity of Yiddishland, from theater posters and youthful memoirs to illuminated synagogue ledgers and rare music scores.

The result, says Jonathan Brent, executive director and CEO of YIVO, is a “reawakening of YIVO’s historic mission, an important (and successful) experiment in international cultural activity, and an irreversible marker of YIVO’s future as a leading global Jewish institution.”

In a Zoom call, the New York Jewish Week spoke to Brent and Stefanie Halpern, director of the YIVO Archives, about the diverse collection, the efforts that made the reunion possible and the ways a new generation of scholars and regular folk can use the archives to expand their understanding and appreciation of a vast and endlessly surprising Jewish past.

The interview has been shortened and edited for clarity.

New York Jewish Week: Jonathan and Stefanie, give me a sense of the significance of this project and how it’s a game changer.

Jonathan Brent: YIVO has never done anything like this in its history — a $7 million project over seven years, involving 11 archivists. It is an international project that has social, historical and also political meaning. It is a step forward into the future for YIVO, even as it is a step backward into the past and the recovery of all of these extraordinary materials. It has demonstrated the viability of international cultural projects on the subject of pre-war Jewish culture, and what can be accomplished with the right spirit and the right focus and the right talent and the right leadership.

It is a project that establishes YIVO as a leading institution in various different ways, in terms of archival science, preservation, accessibility and the putting of a massive amount of material online — making it available, constructing the proper website, using all of the proper software, engaging all the proper specialists to make these materials available online around the world. But it’s also a step forward for us in terms of building the infrastructure of the organization.

YIVO has also become an archival training institution under Stefanie’s leadership, whereby we are training a new generation of specialists who can conserve, process and digitize this tremendous wealth of Jewish materials.

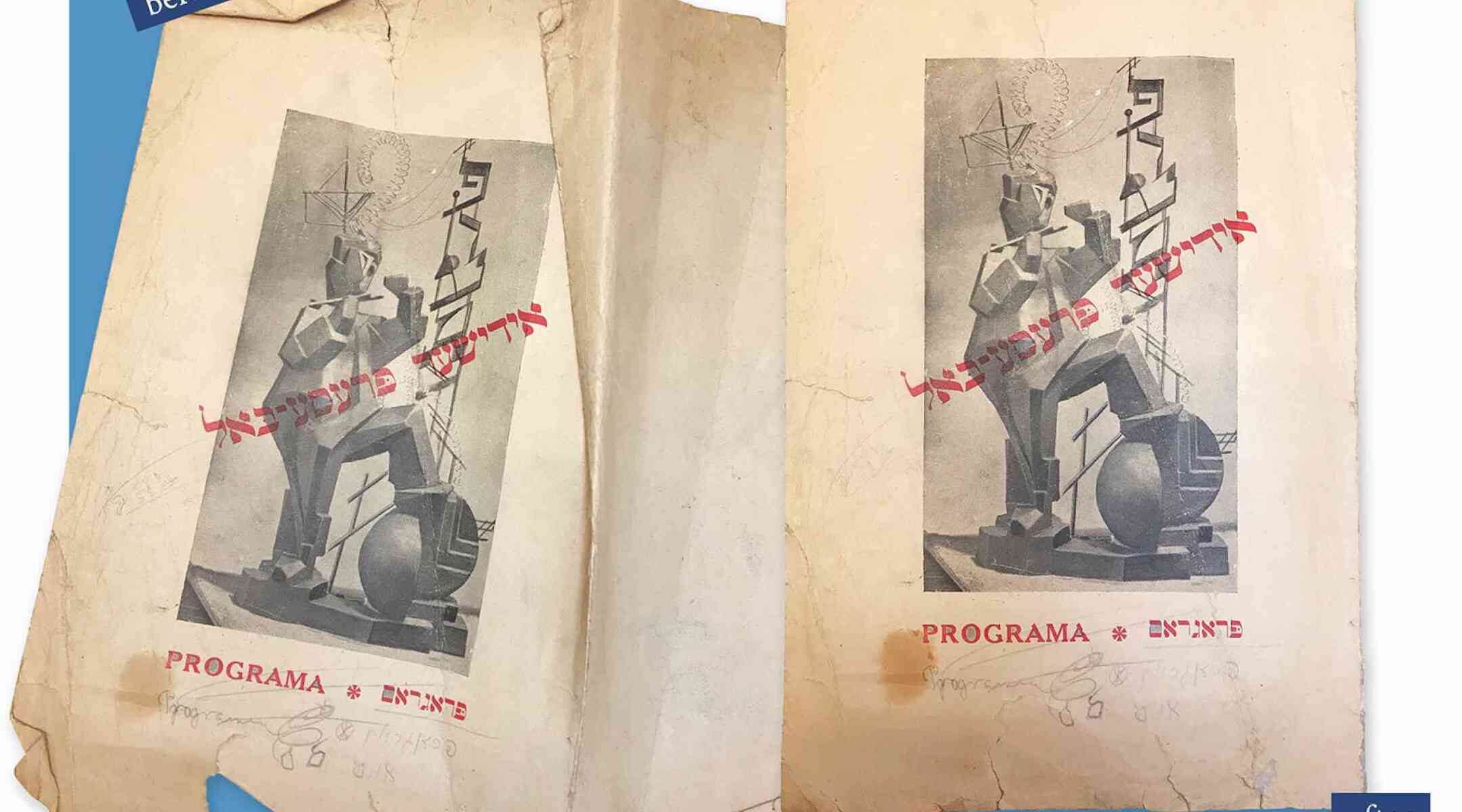

The Edward Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections project includes a scrapbook of Zygmunt Turkow’s earliest Yiddish theater experiences, beginning in 1913. (YIVO)

Stefanie, can you describe how researchers will experience the archive? And what’s gained and what’s lost if you’re working in a digital-only format and don’t have the documents to hold in your hands?

Stefanie Halpern: Part of what we try to do with our digitization method is replicate the experience as much as possible of sitting in the reading room. Of course, you can’t replace the physicality of touching a document, flipping it over, feeling the brittle pages, smelling the leather. But we try to shoot the documents so that you see all of the edges. You see the bends, you see the tears. We don’t sanitize the materials. As you’re scrolling through the materials, we try to replicate what you would actually see in the reading room.

And so, this opens up research to a whole slew of people who just never had access to these documents before. It allows younger researchers or non-academic researchers to feel comfortable accessing them. We see a lot of family historians who are using these materials and wouldn’t necessarily be in the reading room, and I think that’s really great.

Can you give me an example of how people are using the archive?

Halpern: The music collections are just top of my mind right now, because they’re the ones we’ve most recently gotten online and the ones that have been oftentimes least accessible. I’ve had a scholar from Israel email me every month for almost the past year, asking if handwritten manuscripts of operettas are available.

A collection that we’re putting up this week is “Group 1.2,” the YIVO Ethnographic Commission records. The materials that zamlers (amateur collectors) acquired included folklore materials, songs and children’s games. All of those materials are often written on tiny scraps of paper that are extremely difficult to read. Online you can blow them up as big as you want. I know a lot of people are really excited to get their hands on these materials, some of which actually have never been made available to researchers.

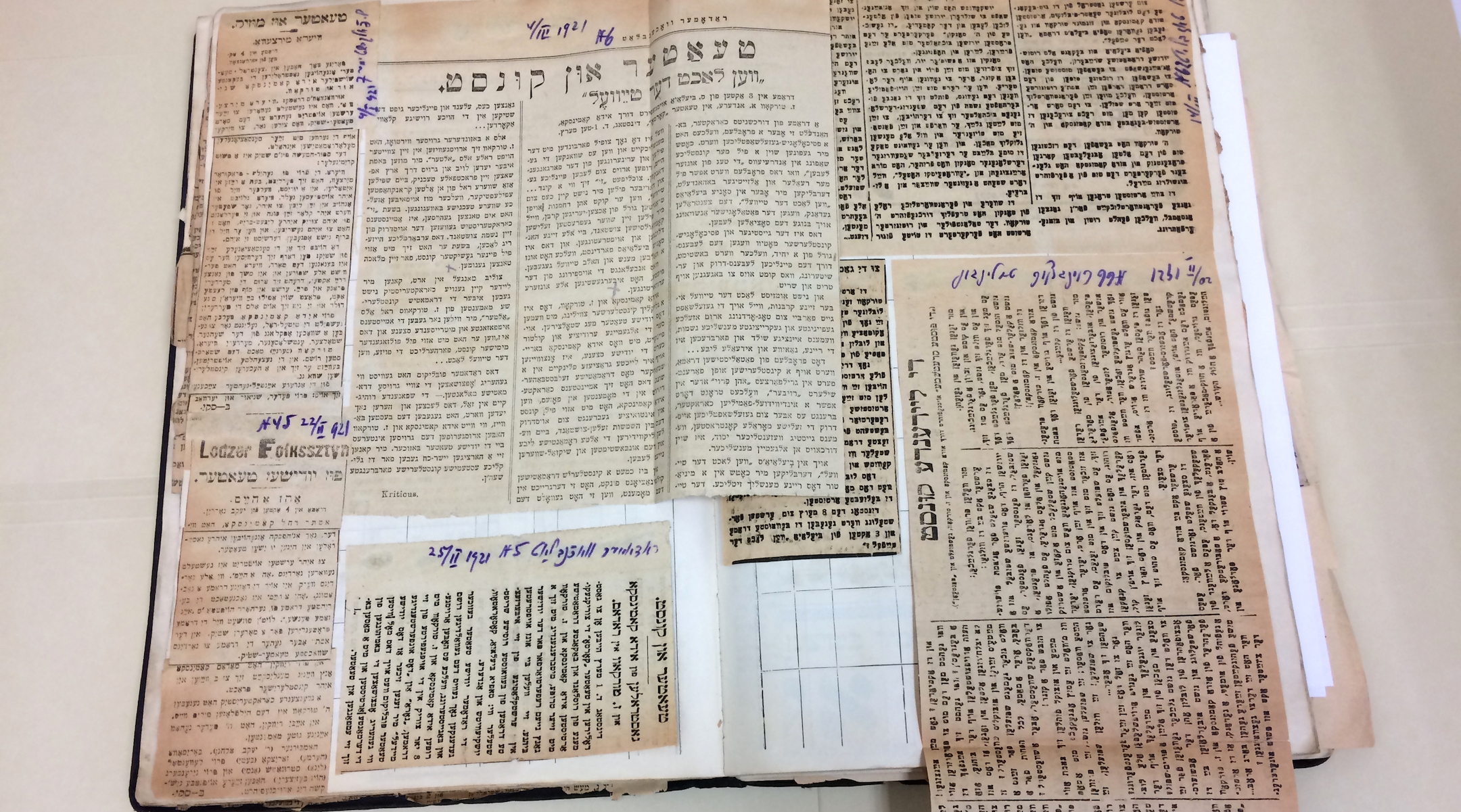

We have the youth autobiographies that were collected by YIVO in the 1930s. We have several hundred of them, but sometimes a few pages are missing and archivists here and in Lithuania were able to connect and actually find the missing pages. Many scholars use the autobiographies because they are such a great snapshot of different types of Jewish life across Poland.

The raunchy stories, the pornographic materials in this collection, were hidden from view for a very long time. These materials were collected by YIVO. They were part of life. It’s that kind of stuff that’s going to create new scholarship and change the scholarship that’s out there.

I have to ask: Who was creating raunchy pornographic Yiddish materials in the 1930s?

Halpern: The context for these is a little fuzzy, but we think they were stories that zamlers collected. They went out and they asked people, you know, what stories do you know about Jewish heroes? What stories do you know about talking bears? What dirty stories do you know?

Brent: Binyamin Harshav [the late Israeli poet and translator] told the story of going out into the marketplace, at the instruction of Max Weinreich [a co-founder of YIVO and editor of the “Modern Yiddish-English English-Yiddish Dictionary”] in order to collect obscenities used by women in the marketplace. And he would do so by irritating them to the point at which they would curse him out.

Another example of the use of this is that we are now working in Vilnius with the Tartle Gallery on an exhibition of material that has been digitized by YIVO for display in May or June. It will be the first major exhibition of prewar Jewish materials in Vilnius since the Jewish Museum there was shut down by the Soviets in 1947 or ’48. So these materials are not only igniting scholarship over here, but they will ignite a renaissance of knowledge of the Jewish world for Lithuanians and for the remnant of the Jewish community there.

Why is that important?

Brent: You have to be very careful about making assertions about another country and society. Of course, I remember very well, when the Polin Museum opened in Warsaw, everybody said “This is a game changer. It’s going to change Polish attitudes toward Jews.” But look where we are today. But I do know that our project is making it possible for young Lithuanians to discover their own past, whether they’re Jewish or not Jewish. Jewish culture is part of Lithuanian culture; it was an inextricable part of what Lithuania became. What it will lead to, I don’t know, but I do know that the YIVO project has been part of this awakening, and through our project people of goodwill, people with democratic instincts and desire for openness, are finding a way of further reinforcing their attitudes.

The Edward Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections project includes quotidian objects like this page from Russian-born watchmaker Shalom Schwarzbard’s notebooks, with a list of expenses. (YIVO)

Are there underexplored parts of the collection you’re hoping a scholar will at last be able to access?

Halpern: We have about, I don’t know, 5,000 or 6,000 posters that have been digitized as part of the project, including over 2,000 Yiddish theater posters that were collected by YIVO during the interwar period, not just from Eastern Europe but from around the world. Posters are extremely difficult to take care of and show to researchers, so a lot of these have never been seen. Theater posters, election posters, posters advertising lectures on health-related things, political things, even hypnotism.

Museums are always interested in borrowing posters, but many of them were in six or eight different pieces. Our conservators were able to piece everything together, so you see that digitization is not just an act of access, but preservation. You can look at those digital images as much as you want and know that you have as accurate a representation of these materials as you can get.

We have the papers of Zemach Shabad. He was a public figure and a private physician in Vilnius, and we have thousands of his medical records that have never been used by researchers. I’m excited for a medical historian to glean whatever information they can from records over the course of 30 years.

Brent: Remember that the culture was destroyed first by the Nazis, then by the Soviets. You cannot separate that history from these materials. But this project is a celebration of what has been preserved through the efforts of generations of Jews who take care of their history, to understand themselves, to pass that knowledge on to the next generation. I cannot tell you the pleasure that it gives me to know that young people are studying these materials. That knowledge of ourselves is not something that’s 2,000 years old or 1,000 years old or 500 years old. It lives in all of us. And somehow we are connected to that past. And so this helps give us more self knowledge, and that’s what our institution wishes to celebrate.

The history of trying to unite the two libraries was very sensitive and was caught up in a legal and diplomatic dispute over ownership with Lithuania, which believes the materials are part of its national heritage. I understand you have a strong relationship with the Lithuanian government, but is there some disappointment that these great collections are not going to be together in the same physical space?

Brent: There’s disappointment for various people who would like to see it so united. I myself am not disappointed in the sense that I never expected it to be. I accepted the status quo. I accepted the historical fact that had not been altered after 20 years of litigation. But yes, there are many people around the world who would like to see all of these materials safe and sound at the YIVO Institute in New York City. But that’s not something that we concerned ourselves with. That was not our job.

In addition to documents and books, the Edward Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections project includes material objects like this series of Russian military decorations collected by Elias Tcherikower. (YIVO)

It is impossible to separate the centuries of Jewish life in Eastern Europe from the communities’ destruction in the Holocaust. Do you see YIVO’s efforts as a memorial project, or one of preservation? Does a sense of mourning shadow your work, or are you able to see beyond the losses?

Brent: Yes, there is a pall of mournfulness over all of this and a sense of loss, but the power of this project, in terms of preservation and bringing forward the past into the present day, is something that I don’t think we even know how to calculate. It will lead to all kinds of new energies. I didn’t get into this business because of the destruction of this civilization. My interest has always been on the living culture, on all of the strange and interesting things that happened in Eastern Europe and how those came to America. My goal is to show the living culture, to change the narrative, to shift it from just the Holocaust and to actually bring these vibrant lives into the fore.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.