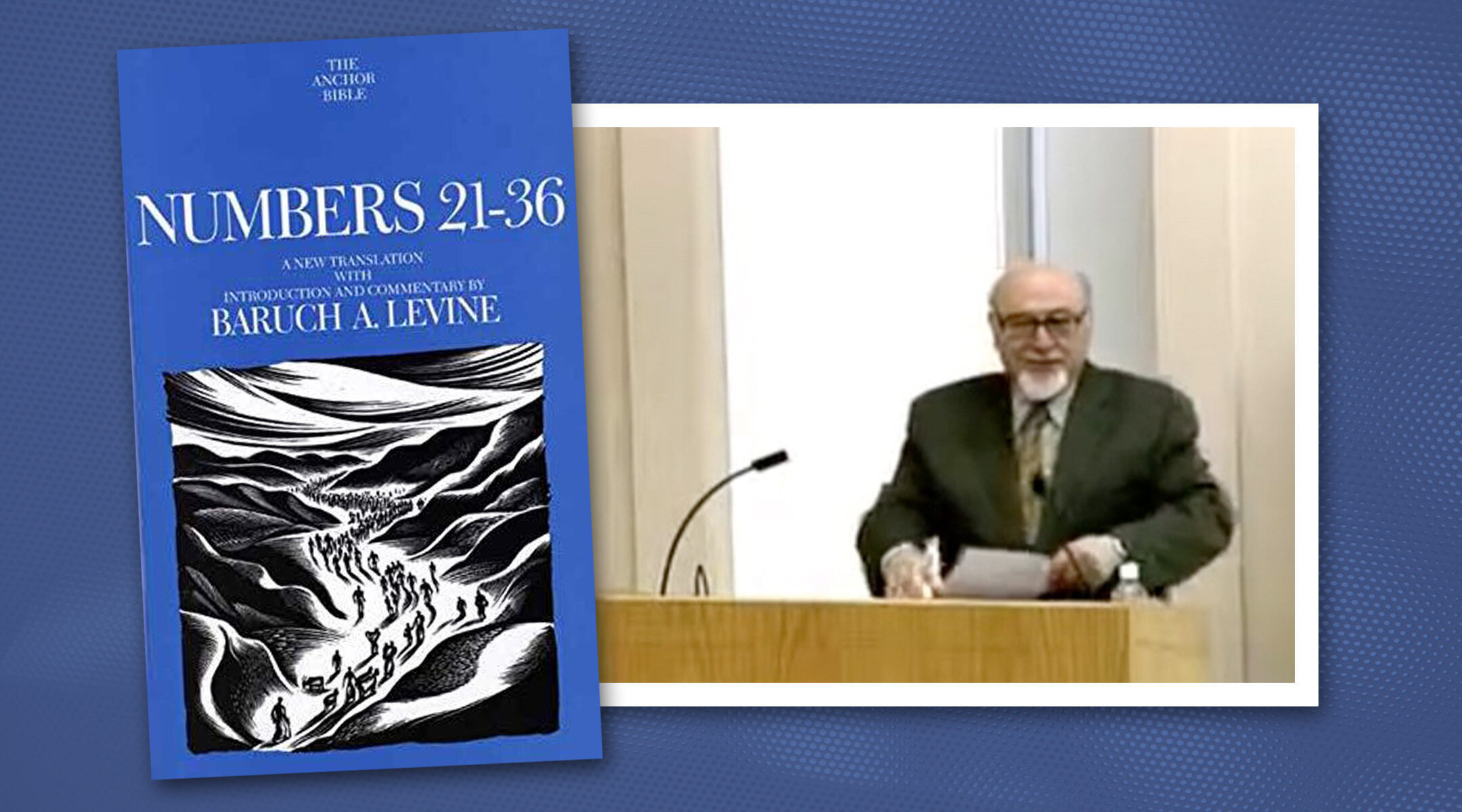

(New York Jewish Week via JTA) — Baruch A. Levine, a Bible scholar who wrote the two-volume Anchor Bible commentary on the book of Numbers and the Jewish Publication Society commentary on Leviticus, died Dec. 16 in Hamden, Connecticut. He was 91.

The Emeritus Skirball Professor of Bible and Ancient Near Eastern Studies at New York University, Levine used the tools of philology and semantics — that is, language and context — to compare ancient Near Eastern texts in order to unlock the meanings of the Hebrew Bible and “reconstruct its literary history,” as he once explained.

Brandeis University historian Jonathan Sarna, in a Facebook post, called Levine “one of the great Jewish Bible scholars of his generation.”

Levine taught at Brandeis from 1962 to 1969 before coming to NYU, where he played a central role in developing what became the Skirball Department of Hebrew and Judaic Studies. Levine also helped found the Association for Jewish Studies and served as its second president from 1971 to 1972.

In 2011, 51 of his scholarly articles were collected in a two-volume set titled “In Pursuit of Meaning: Collected Studies of Baruch Levine.”

Levine was born on July 10, 1930, in Cleveland, Ohio and attended public schools. In 1951 he earned a B.A. in Comparative Literature from Adelbert College of Western Reserve University. He was ordained a rabbi in 1955 at the Jewish Theological Seminary, where he studied under a fabled group of scholars that included H. L. Ginsberg, Saul Lieberman, Salo Baron and Shalom Spiegel. During the summers he served as a counselor and unit head at Camp Ramah in the Poconos and as director of Camp Yavneh.

After service in the U.S. Army Reserve, he briefly served as a pulpit rabbi before enrolling as a doctoral student at Brandeis University in the Department of Mediterranean Studies.

In 1969, after teaching at Brandeis, he was appointed Professor of Hebrew and Near Eastern Languages in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Literatures at NYU. According to a biographical sketch by Lawrence Schiffman, a colleague at NYU, Levine “championed the notion that Judaic studies had to be integrated intellectually with other related disciplines and that the same academic standards applying in other disciplines had to be applied [t]here.”

Stuart S. Miller, a specialist in ancient Judaism and Professor of Hebrew, History and Judaic Studies at the University of Connecticut at Storrs, studied with Levine in the 1970s at NYU and remained in touch with him over the years. “It was in Professor Baruch Levine’s classes that I was first exposed to critical methods of studying the Bible and became aware that the fusion of the traditional and the modern modes of inquiry could result in more fruitful and stimulating investigations of the text,” he recalled Tuesday. “It was in his undergraduate and graduate classes, furthermore, that I began to wrestle with the possible ways in which the texts of Jewish tradition reflect the societies of the peoples that produced them.

“Professor Levine’s influence also extended beyond the classroom,” Miller continued, “as I have always found his profound (and numerous!) perspectives on the life of the scholar — and much else — most illuminating. And to all, his students and colleagues, he brought contagious encouragement and good cheer. He was the consummate academic scholar and teacher of Torah.”

In 2003, after his retirement from NYU, colleagues honored Levine with a conference on Semitic papyrology, one of his specialties, and a collection of papers edited by Schiffman.

His wife, Corinne (Godfrey) Levine, died in 2016.

In a 2012 autobiographical essay, Levine described the Hebrew Bible as “a repository of ancient Near Eastern heritage. It preserves language and law, religious practices and social patterns, political norms and historical memories indicating that its authors, living in a small Levantine country, were open to the world.” This “critical” reading of the Bible, he wrote, differed greatly from the traditional Torah education he received in his youth, but as a result, “the Hebrew Bible now means even more to me!”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.