(JTA) — In “The Social Justice Torah Commentary,” Rabbi Brian Stoller describes a turtle-shaped dinner bell that his great-grandmother used to summon a Black butler to attend to her needs at the family’s Shabbat table.

When I got to that line while editing the volume, I felt a jolt of familiarity: An identical bell served the same purpose at my own grandmother’s table.

All of my grandparents — and all four of my American-born great-grandparents — hailed from the South, and social justice activism was not baked into my DNA.

Yet unlike many “old” southern families, I was raised without glorification of the Confederacy. As a preteen, I only learned that both of my parents are descended from Confederate veterans because I asked. My parents, members of the Silent Generation, were not engaged in the civil rights movement of the 1960s. However, unlike most members of the privileged Houston Jewish community in which they were raised and in turn raised my sister and me, they opened their eyes to social injustice in the 1970s and exposed us to progressive thought and activism, rooted in Reform Jewish life.

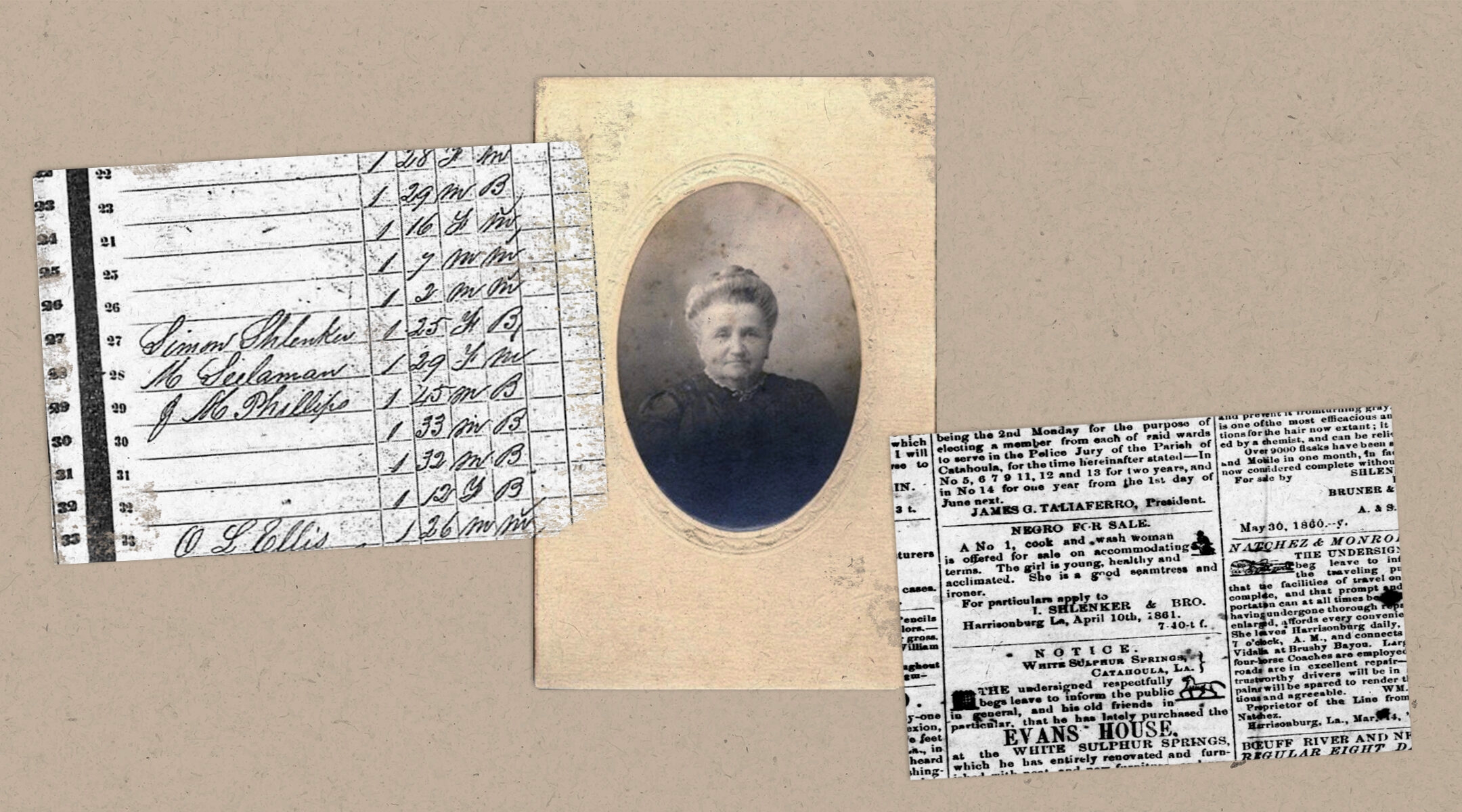

As I neared the end of my work on “The Social Justice Torah Commentary,” a distant relative sent me a page of the 1860 Louisiana slave census, the first documentary proof for me that an ancestor — my great-great-great-grandmother, Magdalena Seeleman — was a slaveholder.

Magdalena Gugenheim Seeleman was born Dec. 25, 1810, in Zweibrucken, Germany. She first shows up in the U.S. Census in New Orleans in 1850. She is listed in the 1860 U.S. Census as living in the home of her daughter and son-in-law, Simon and Caroline Shlenker, in Trinity, Catahoula Parish, Louisiana. According to the list of parish slaveholders from June 22, 1860, “M. Seeleman” was the owner of a 29-year-old woman described as “mulatto.” Right above, Simon is described as the owner of a Black woman, age 25.

Simon’s brother Isaac was married to Caroline’s sister Charlotte; Isaac and Charlotte were my great-great-grandparents. Isaac and Charlotte are not on the list of slaveholders, but a document says Isaac received payment from the state of Louisiana for serving as a prosecutor of escaped slaves. In an advertisement dated April 10, 1861, Isaac “and Bro.” offer a “Negro” for sale; the “girl” is described as “young, healthy and acclimated.”

The information is as horrifying as it is unsurprising. When I visited The National Memorial to Peace and Justice in Montgomery in 2019, I found memorials indicting Catahoula Parish, Louisiana, where Seeleman lived, as the site of multiple racist terror lynchings. All five of the other counties and parishes where my family thrived during the lynching era are similarly accused there.

At Montgomery’s Legacy Museum, I confronted a sign offering a reminder that many of the same families who were enriched by enslaving Black Americans continue to enjoy that prosperity today. Their wealth, inherited down the generations, cannot be separated from the enslaved human beings that their — that is, my — ancestors oppressed to earn a generous living.

Earlier in my career as a rabbi, not yet entirely aware of my family history, I did not focus on racial justice in my work, but rather on immigration reform, abortion rights and LGBTQ equality. I became outspoken to the point that, when I was seeking to leave my previous congregation for a new pulpit, a friend in lay leadership hoped that I would look in “blue states.” Instead, in 2013, I took the pulpit of Congregation B’nai Israel in Little Rock, Arkansas, where I was truly awakened for the first time to the moral urgency of advancing racial equality in our nation.

Founded in 1866 on the heels of the Civil War, B’nai Israel counts Confederate veterans among its earliest leaders, men who had risked their lives to maintain chattel enslavement of Black Americans. But the synagogue’s subsequent history shows how a commitment to justice can emerge even in places where racism and inequity might initially have been baked into its DNA.

When I joined the congregation, members shared with me the storied legacy of the late Rabbi Ira E. Sanders, an early hero of the civil rights movement. During his first months in Little Rock in 1926, Rabbi Sanders lent his body to the struggle against segregation, refusing to move from the back of a streetcar. He would go on to lead the integration of Little Rock’s public library. Later, congregants — women, in particular, including descendants of the Confederate soldiers who founded the congregation — heeded Rabbi Sanders’ call to organize against segregation in public schools.

Rabbi Sanders retired the summer I was born, a half century before my arrival in Little Rock. His predecessors and successors, along with their partners in lay leadership, established a legacy of social justice activism, calling on congregants and me to continue that critical work. Their legacy inspires my belief that, rather than solely focusing on the guilt and shame of historical sins, the best recourse is to take action to repent for and rectify them.

As for the woman my ancestor enslaved, my distant cousin has been working to identify her, in the hope of locating descendants in order to offer at least some form of reparations. I do not know if we will ever be able to name her or her descendants. I dedicate “The Social Justice Torah Commentary” and any social activism I can muster to her memory. And I pray that the work we all do to advance social justice today may serve as tiny measures of atonement for the grievous damage caused by our nation, including my ancestors, to her and millions of Black Americans across four centuries and counting.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.