(JTA) — Scholars do not know exactly when Jews first came to Penang, one of the smaller states in Malaysia, located on the Southeast Asian nation’s western island.

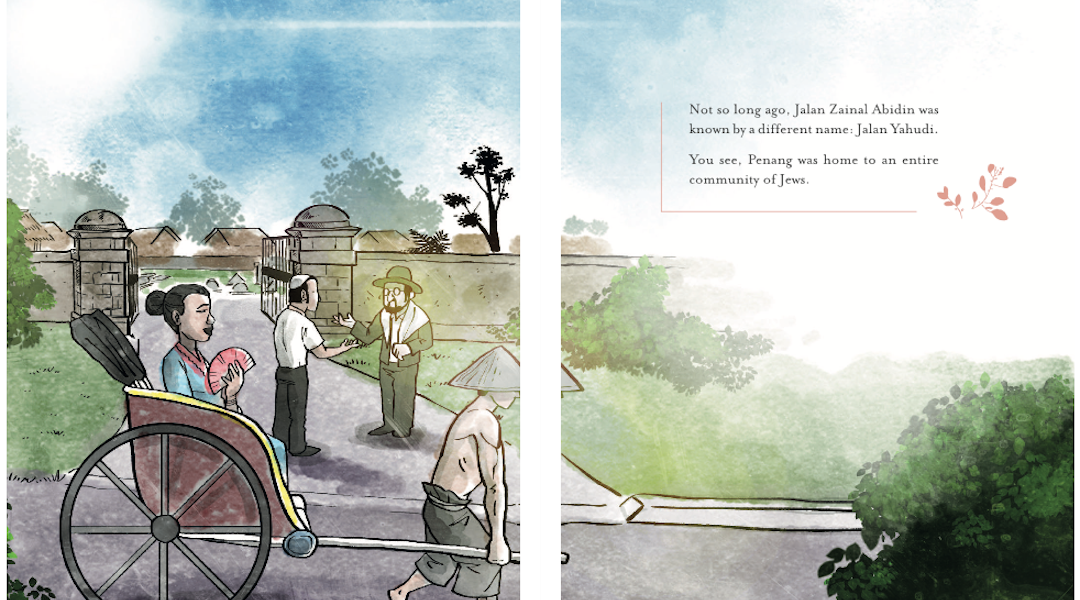

The Jewish cemetery in the region’s capital city of George Town, on a street formerly called Jalan Yahudi — “Jewish Way” — gives an estimate: its first burial was of a Mrs. Shoshan Levi, in 1835. By the turn of the 20th century, a census showed a Jewish population of 172.

But Jews no longer roam the streets of George Town, and haven’t in large numbers for decades. Jalan Yehudi has since been renamed for a Malay writer, Zainal Abidin, and the former synagogue around the corner has not been inhabited by Jews since it closed in 1976. Without enough Jews to fulfill a minyan, or Jewish prayer group of 10 men, the building is now a trendy coffee shop.

And in recent years, Malaysia has been identified by the Anti-Defamation League as among the most antisemitic nations outside of the Middle East and North Africa. Much of that hatred can be credited to its former prime minister, Mahathir Mohamad, who famously declared himself proud to be antisemitic. Israel and Malaysia do not maintain diplomatic relations and Israelis are barred from visiting.

“The only thing that does exist [in Malaysia today] are people of Jewish origin, say, people who have a Jewish ancestry somewhere in the family tree, but those people converted to Islam in order to intermarry into the Malay community,” said Zayn Gregory.

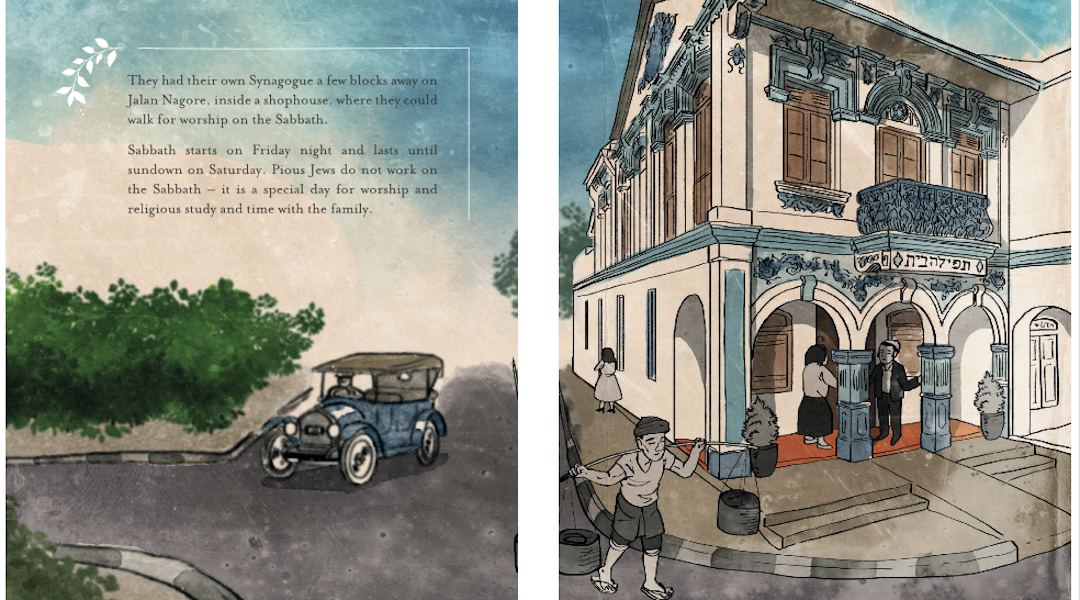

Gregory, an American who himself is a half-Jewish convert to Islam and now lives in the Malaysian city of Kuching, has recently penned a book about Penang’s Jews. “The Last Jews of Penang,” which was published last week, is a short, all-ages graphic novel, complete with colorful watercolor illustrations of old George Town streets and synagogue scenes by artist Arif Rafhan.

(Matahari Books)

It profiles the history of the once-vibrant Jewish community that occupied old George Town, explaining Jewish ways of life for readers who may have never met a Jew, and highlighting some of its famous figures like David Marshall, who would go on to become the first chief minister of Singapore (under British Commonwealth rule).

“The book is sort of a requiem for the community that used to be — those who are aware of the vanished community have a sense of the way in which we have been diminished by their passing. The hope is this book will bring more awareness to the rich multicultural reality of the Malaya [the name of the region until the early 1960s] that used to be,” said Gregory, who is a lecturer in landscape architecture at the University of Malaysia Sarawak and a writer and translator of Malay poems.

He became fascinated about the little-known history of Jews in Malaysia through stories he read in local news outlets, and was later approached about the idea by the book’s publisher, Matahari Books.

Gregory converted to Islam at age 17, a decision he credits to being caught in the middle of a mixed Jewish and Christian family, not strongly identifying with either. He later made the decision to move to Malaysia with his wife, whom he had met in the United States but was born and raised in Malaysia. The country is more than 60 percent Muslim, with nearly 40 percent of people identifying with other faiths.

Judaism wasn’t a big part of Gregory’s life before moving to Malaysia, he said. “But being here, it’s a country where Judaism is not widely known or understood. Most people have never met a Jew in their life. And there’s unfortunately a lot of misunderstanding and, you know, sort of prejudices born out of ignorance.”

Doing the research and writing the book brought him closer to his Jewish roots. When he learned that there was once a Jewish community in Malaysia, “that really clobbered me. I was so amazed,” Gregory said. “I felt like it was really an opportunity for me to share something about myself that is still very much a part of me.”

Little research or significant writing has been done about the Penang Jews — Gregory used mostly local newspaper and magazine articles, in addition to one study written by Australia-based researcher Raimy Che-Ross. According to that paper, the Zionist nationalist Israel Cohen paid a visit to Penang in 1920, then under British control, where he met a man named Ezekiel Aaron Manasseh, who claimed that he was until recently the only religious Jew there.

Trade interests, antisemitism in their home countries, and World War I had brought “a few other Jews from Baghdad, mostly poor peddlers, who consorted with Chinese and Malay women, and lived debased lives,” claimed Manasseh, who was Orthodox. It wasn’t all true, as census data shows — but Manasseh showed that even in a place as small and distant from a major Jewish community as Penang was over a century ago, timeless Jewish turf wars persisted.

Many Jews began leaving Malaysia during World War II with the help of the British. Those who stayed mostly left by the 1970s as antisemitism became more pervasive in everyday life.

A view of the building that used to house the Penang synagogue. (Google Street View)

In a 1970 book, Mahathir Mohamad, the former prime minister, wrote that Jews are “hook-nosed” and “understand money instinctively.” He was ousted from office in 2020 during his second stint as prime minister, by which time the Jewish population of Malaysia had all but vanished.

Of his antisemitism, Mohamad said in 2012, “How can I be otherwise, when the Jews who so often talk of the horrors they suffered during the Holocaust show the same Nazi cruelty and hardheartedness towards not just their enemies but even towards their allies should any try to stop the senseless killing of their Palestinian enemies.”

Those who fled Malaysia went to Australia, Israel and the United States; many others would go to nearby Singapore, including Marshall.

The last known ethnic Jew in Penang was David Mordecai, a well-known hotel manager whose family first came from Baghdad in 1895 and who died in 2011. He is buried in Penang’s only Jewish cemetery, which has been cared for by the same Muslim family for generations.

Scholars have said the loud voices of politicians do not necessarily reflect the opinions of everyday Malaysians; they argue that many who reject the country’s religious nationalism have begun to reject the country’s tradition of Jew hatred.

Gregory agrees, and hopes his book will help build bridges with the faraway Jewish people that he still considers a major part of his life, and who once called Penang their home.

“The many times that I have shared here with people about my own background, I have never experienced anything remotely hostile,” Gregory says. “Some amazement sometimes — certainly the idea of a person of Jewish background becoming Muslim is just as surprising to a Muslim as it might be to a Jew.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.