(New York Jewish Week via JTA) — More than two decades after publication of allegations that Rabbi Baruch Lanner abused teens in his charge for more than 30 years, four of his victims are seeking their day in court.

The four women, now middle aged and older, filed a lawsuit today with the Superior Court of New Jersey in Middlesex County against Lanner, the Orthodox Union and the National Conference of Synagogue Youth, the OU’s youth arm, where Lanner was a top official.

It is believed to be the first such legal action taken against the Orthodox organizations as a result of the scandal involving Lanner, 72, who was forced to resign days after The Jewish Week published in 2000 an investigation that detailed charges against him by more than a dozen former NCSY members.

The revelations emboldened other accusers, and in 2002 Lanner was convicted of sexually abusing two teenage girls who were students in the 1990s at the Hillel Yeshiva High School in Deal, New Jersey, where he had been principal in between stints at NCSY. He was sentenced to seven years in prison, served nearly three years and was released on parole in early 2008.

The lawsuit focuses only on his time at NCSY, according to Boz Tchividjian, the lawyer representing the plaintiffs. He said it alleges that the two prominent Orthodox organizations knowingly allowed the rabbi’s predatory behavior at its youth group to continue despite numerous, long-standing complaints that he sexually, physically and emotionally abused girls and boys in his role as NCSY’s director of regions.

The suit was filed under recent changes in New Jersey law that allowed for a two-year “lookback” window during which sexual abuse victims could come forward and sue their abusers and their enablers. That deadline is Nov. 30, prompting the four women to file their lawsuit now. Previously, a statute of limitations in New Jersey had inhibited any civil suits against the Orthodox organizations that employed Lanner.

“Our clients are going to finally hold Baruch Lanner accountable for his deplorable and abusive conduct, and the Orthodox Union accountable for giving a known offender decades of access to vulnerable children who he terrorized and victimized,” said Tchividjian. “By filing this lawsuit, these bold women are reclaiming the power that was taken from them by a perpetrator and the organization that employed him and empowered him.”

Another attorney for the plaintiffs, Brian Kent, of the law firm Laffey, Bucci & Kent in Philadelphia, said participants might still be added to the lawsuit if they come forward by the deadline Tuesday.

Asked to respond to the women’s accusations in the days before the suit was filed, a spokesperson for the OU told The Jewish Week: “The OU is not aware of any impending lawsuit and therefore cannot comment.”

Among the charges in the lawsuit, according to Tchividjian, are that the OU and NCSY were negligent in failing to protect children — that instead they protected themselves by ignoring or dismissing complaints about Lanner’s “willful, malicious and wanton” actions for decades.

Even by 2000, when the Lanner story came to light, the statute of limitations had long passed for those complainants, preventing them from taking legal action. The article received national and international attention and was cited as “a watershed in the way the Orthodox community addresses sexual abuse,” according to the Baltimore Jewish Times.

But the women bringing the lawsuit are among those who believe the problem persists, and that despite impressive written policies and standards, systemic cultural change is still required at the OU and NCSY as well as other Orthodox institutions.

“What’s needed is for organizations to protect their members, not just protect their organizations,” said Jessie (not her real name), one of the four plaintiffs in the lawsuit, in an interview with The Jewish Week. “

[The four women are not named in the lawsuit, their attorneys said, and in response to their request for privacy, they are not named here. The pseudonyms are for the purposes of this article.]

“For now, the culture is to do what is technically defensible,” Jessie said, “rather than what is the right thing to do for all members.”

She noted that while the Reform and Conservative movements are in the midst of major internal reckonings on sexual misbehavior and moral accountability concerning their clergy, and making the information public, the Orthodox community leadership has not announced any such action.

Jessie also said that neither she nor the other Lanner victims she knows were ever approached by the OU or NCSY to apologize or offer assistance after their experiences became known through The Jewish Week report in 2000.

This week, two of the four women who brought the lawsuit spoke with The Jewish Week. They each recalled their separate traumatic experiences with Lanner, dealing with his aggressive sexual behavior and violent temper when they were teens in the 1970s — much of it detailed in the Jewish Week article and in the current lawsuit. And the women explained why they chose to take legal action now.

Jessie was 16 when she became involved with NCSY in 1974. One weekend she attended a Shabbaton in Asbury Park, New Jersey. Lanner had arranged for her to sleep at a home next door to the home where he was staying, she said. At night, when no one was around, “he tried to kiss and caress me.” When she pushed him away and threatened to tell a rabbi’s wife about his behavior, “he put his hands around my neck and began strangling me. Only when he saw that I was losing consciousness did he stop. And he walked away without a word.”

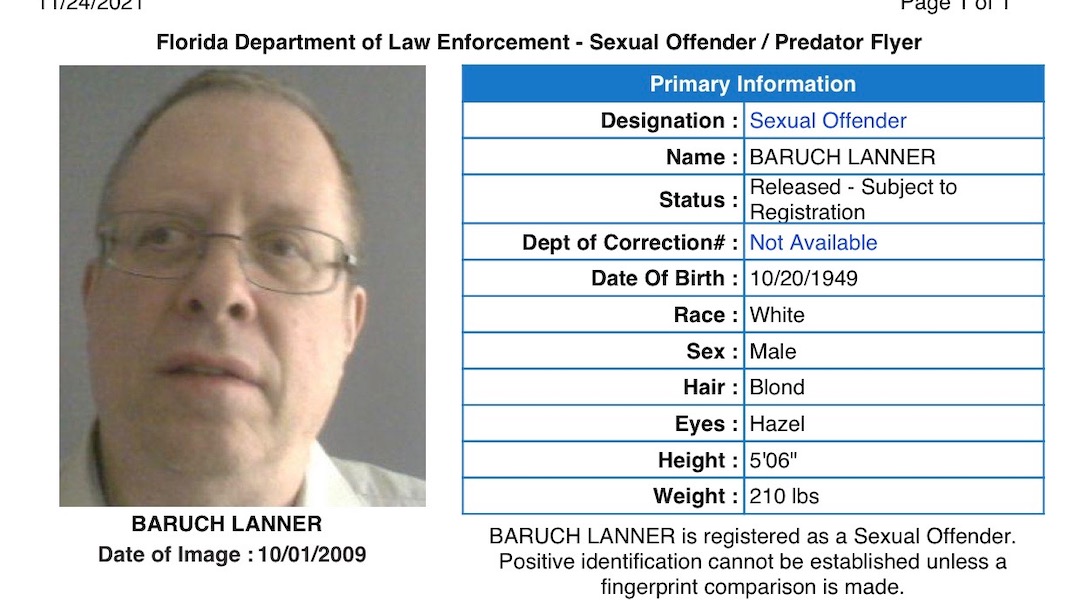

A flyer from the Florida Department of Law Enforcement’s Sexual Offender registry lists Baruch Lanner’s status as “Subject to Registration.” Lanner was convicted of sexually abusing two teenage girls who were students in the 1990s when he was principal at the Hillel Yeshiva High School in Deal, New Jersey. (Via FDLE)

Jessie said she told no one at the time because she realized it was futile to do so. There was “a sense of conspiracy of enablers and a sexualized atmosphere” at Lanner-led NCSY events, she said, with the rabbi engaged in “explicit sexual kidding, talk of body parts,” commenting on girls’ figures, and similar behavior. The male advisors, mostly college students, “observed all of this and understood that it was ok to cross boundaries, to touch girls.”

But the excitement of being part of a close-knit social and religious group led by a charismatic rabbi kept Jessie and other youngsters actively involved in NCSY.

The following year, when Lanner chose Jessie to be regional president of NCSY, she agreed on the condition that he not molest her. If he tried, she told him, she would report him to Rabbi Pinchas Stolper, the founding director of NCSY.

In response, Lanner “laughed at me,” she recalled, “and said, ‘they all know about me,” including Stolper. In the 2000 article, Stolper acknowledged there were several complaints from young women many years previously about improper behavior by Lanner, but said he found no real substance to the charges.

Attempts to reach both Lanner and Stolper for this article were unsuccessful.

During her time as president, Jessie said she “witnessed Lanner prey on multiple 14 and 15-year-old girls,” according to the lawsuit.

She told The Jewish Week “it was inconceivable” that the leadership of the organization did not know of Lanner’s behavior.

Nancy (not her real name) was 15 in 1974 when she took part in NCSY’s annual summer program in Israel at Lanner’s urging. At one point during the tour, Lanner called her into his room and questioned her loyalty to him, threatening to send her home or transfer her to another tour group, she said. When she began to cry, the rabbi told her she could prove her loyalty by kissing him on the cheek. She did, and he told her she could stay.

He paired her with another girl, Sarah (not her real name) as roommates. Nancy witnessed how Sarah would be called away by Lanner in the evenings to meet with him. “Then my turn came,” Nancy said, “the touching and kissing.” This went on at least a dozen times, according to Nancy.

Once, after grabbing her and asking, “do you love me?” she refused to respond. The rabbi punched her in the stomach, knocking the wind out of her, according to the lawsuit.

Over time, the two girls confided in each other, sharing details of Lanner’s similar pattern of behavior.

At one point, they both claimed to be ill so they wouldn’t have to go to Eilat with Lanner and the group.

On a visit to Bayit V’Gan, Nancy met with an American rabbi and told him what was happening. “He seemed shocked and genuinely sympathetic,” she said, but nothing came of it.

Toward the end of the trip, she approached Stolper, who was visiting for the weekend. “When I told him that Rabbi Lanner was acting inappropriately with me, he said, ‘I’m sure you misunderstood him.’ And then he asked me, “But are you having a good time” on the trip?

“He didn’t seem at all surprised by the allegations,” Nancy said.

The experiences of the other two women were similar to those of Jessie and Nancy, as described in the lawsuit, according to their attorneys.

Susan (not her real name) was 13 years old when she became involved with NCSY. She was “groomed” by Lanner for months, made to feel noticed and special before he began to kiss, touch and grope her when they were alone. This occurred more than 20 times over the next two and a half years.

On an NCSY summer program in Israel, Susan found the courage to say “no” to the rabbi’s advances. He became angry and punched her in the chest. She told no one, fearful that Lanner would send her home.

During the next school year, while riding in a car together, Lanner attempted to pull over to an isolated area and sexually assault Susan.

When she told an NCSY advisor, a young rabbi, he referred her to a higher-up in the organization who, according to Susan, told her: “I inherited the monster. I didn’t create him.”

No action was taken to report Lanner’s behavior then or many other times when Susan told rabbis of the OU, and other rabbis, of being sexually abused by Lanner.

“For me it closed the door for religion,” said an accuser. “I feel that he took advantage of an innocent soul and you can never get that innocence back.”

Laura (not her real name) was 12 when she was active in NCSY. She recalled that Lanner insisted on driving her home one Saturday night from a Shabbaton. He pulled over to a deserted parking lot, she said, told her to take off her shirt and tried to kiss her.

“For me it closed the door for religion,” she stated. “I feel that he took advantage of an innocent soul and you can never get that innocence back.”

The two women who spoke to The Jewish Week in recent days emphasized that their primary motive for filing a lawsuit almost a half-century after some of these painful incidents was not for financial gain or revenge. And that it was a difficult decision to wade into a legal battle against two large, prominent Orthodox institutions.

“It always bothered me that the OU was never really accountable,” Nancy said. “I do want my day in court because I want to see real change. I wouldn’t mind people seeing that a few women can change the way things are.”

Jessie echoed the sentiment, asserting that she wants “to see the culture change around sexual safety in Orthodox institutions.

“No real guilt was admitted. There was no true reckoning. The process of teshuva means acknowledging one’s mistakes, facing the hard truth.”

She said she was “delighted to see” that NCSY released a new Conduct, Policy and Behavioral Standards Manual as of Sept. 17, which includes guidelines on reporting, “grooming behavior,” “boundary violations” and “inappropriate behavior with minors.” “Whether it was because they knew a lawsuit was coming or just a coincidence, it’s a very positive move,” she said.

Jessie added that she hoped the lawsuit will be “an important catalyst.”

Mostly, she holds out the hope that when it comes to safety for all, the actions of the OU and NCSY will be “grounded in Jewish ethics and sources — not because someone is watching these organizations or suing them but because it is what God and our religion demands of us.”

Gary Rosenblatt was editor and publisher of The Jewish Week from 1993 to 2019. Follow him at garyrosenblatt.substack.com

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.