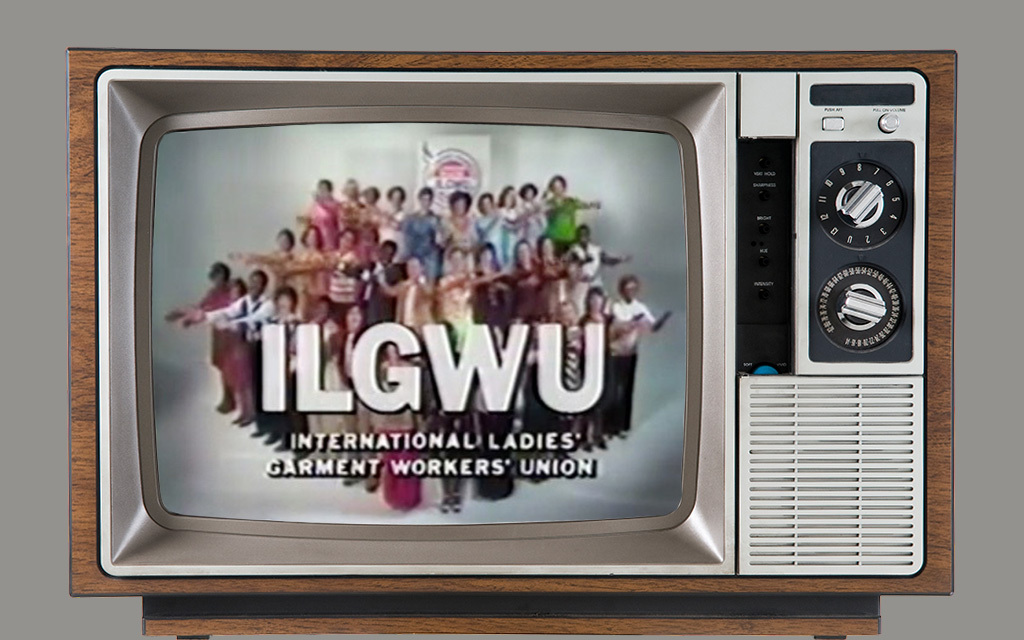

(New York Jewish Week via JTA) — If you watched television in the 1970s and early 1980s, chances are you can sing a few bars of “Look for the Union Label,” a jingle sung on commercials for the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union. The infectious song was meant to prop up what was then the sagging American-made clothing industry, and the ads featured actual union members singing the praises of union-made garments.

The song was more memorable than effective: Labor unions never recovered from a host of trends that shifted power from organized labor to management, as John Oliver explained on Sunday night’s episode of his “Last Week Tonight” show on HBO. Oliver began his segment on union-busting with a clip of “Look for the Union Label,” an early version showing a multicultural cast of women singing the iconic lyrics:

Look for the union label, when you are buying that coat, dress, or blouse,

Remember somewhere, our union’s sewing, our wages going to feed the kids and run the house,

We work hard, but who’s complaining? Thanks to the ILG we’re making our way,

So always look for the union label, it says we’re able to make it in the U.S.A.!

The song always felt vaguely Jewish to me, especially that line, “but who’s complaining?” — which sounds like it was translated directly from the Yiddish. It turns out I was right, up to a point. While the Yiddish trade union roots of the ILGWU are undeniable, and the song’s lyricist was a pioneering Jewish advertising executive, the jingle also has a back story that touches on gender, feminism and the civil rights movement.

The song was discussed in 2019 at an exhibit at the New-York Historical Society, “Ladies’ Garments, Women’s Work, Women’s Activism.” ILGWU, founded in 1909 to unionize workers who made women’s garments, was instrumental in organizing immigrant women, particularly Jews, who worked in the “rag trade.” David Dubinsky, a Russian-born Jew who came to New York as a teenager, served as its president from 1932 until 1966.

As the NYHS show explained, the union reached the height of its power in 1959, when it claimed nearly a half-million members, mostly in the New York area. But by the 1970s, unionized shops were closing throughout the United States and work was being shipped to factories overseas.

As Nicholas Juravich, at the time a postdoctoral fellow at the NYHS’s Center for Women’s History, explained in an essay, “the new ‘union label’ campaign was imagined as a national, industry-wide strategy to build support for the ILGWU beyond its traditional strongholds.” In 1975, he writes, only 1.7 billion garments left union shops, a decline of nearly 40% in just seven years.

The lyrics were by the ad campaign’s director, Paula Green. Green was a Jewish woman who moved to New York from California and became one of the first woman executives in the advertising industry when she founded what would become Paula Green Advertising. (At the famed Doyle Dane Bernbach agency in 1962, Juravich explains, she created the “We Try Harder” catchphrase and campaign for Avis, which the car rental company still uses.) The music was by Malcolm Dodds, a Brooklyn-born, African-American vocalist and choral leader who sang in the ’50s doo-wop group The Tunedrops.

The campaign had to avoid a pitfall of earlier “union label” campaigns, which were often nativist and racist in urging consumers to buy American instead of foreign-made goods.

“They really avoid that kind of ugly nativism conceit that, certainly in the ’70s and ’80s, was bubbling up in parts of the labor movement and in popular culture around jobs going overseas,” Juravich, now assistant professor of History and Labor Studies at the University of Massachusetts Boston, said in an interview Tuesday. “The campaign showcases the creativity and the multiculturalism of the union, and it puts workers and their faces front and center. Because so much of the rhetoric, even in the ’80s, around what happened to the American working class focuses on the white male worker. But the ILG ads are gloriously chaotic and full of people from all over.”

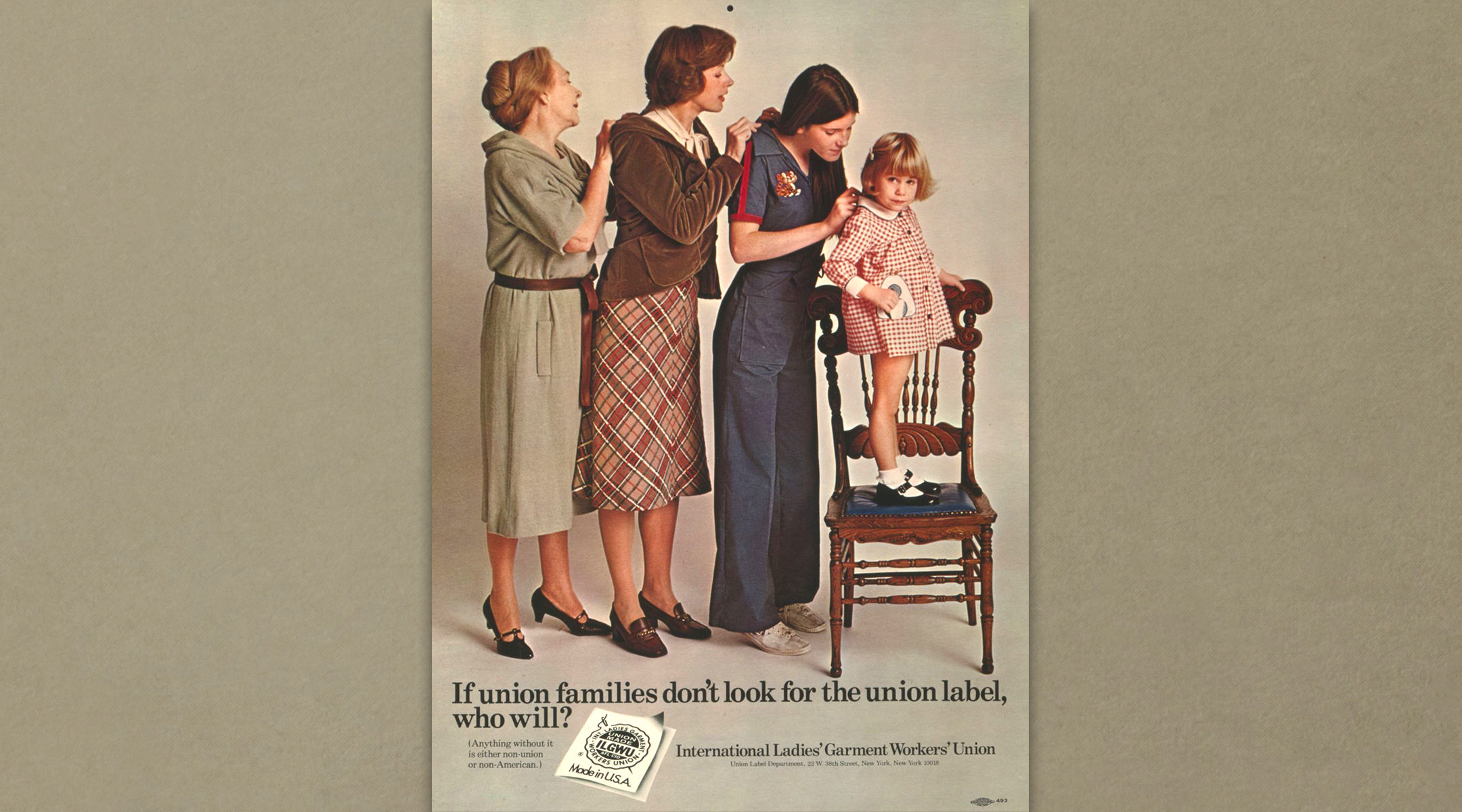

An International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union ad implores union families to buy union goods. (Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

In other ways, too, the campaign fought cliches of unions as male-dominated, cigar-munching syndicates. “I felt particularly close to the women in the union,” Green told The New York Times in 2004. “They are real examples of women’s liberation.”

The song left a cultural imprint: Jimmy Carter called it one of his favorites, Al Gore sang it on the campaign trail, and both “Saturday Night Live” and “South Park” lampooned it. Cory Matthews sings the first line in an episode of the 1990s sitcom “Boy Meets World.”

And the Jewish stamp on the song is unmistakeable, if not immediately apparent. Juravich cites the work of Daniel Katz, a labor historian at CUNY, who argues in his 2011 book “All Together Now” that Yiddish socialism helped create a distinctive workers’ culture that embraced various ethnicities and nationalities. “This socialist tradition infuses the ILG,” Juravich said.

Nevertheless, the song didn’t do much either to sell union-made products or bolster organized labor.

“It’s a great song. It’s a great history,” said Juravich. “The depressing thing is that it didn’t inspire the consumer activism it could have, which required policy-level interventions by the U.S. government. But I do think there’s some positives in the way it really engaged the workers and their story in a very public and deliberate way.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.