NEW YORK (JTA) — Near the start of his Rosh Hashanah sermon last month, Rabbi Benjamin Goldschmidt asked congregants a question: “Is there a person in your life that you feel you have done everything you could do to reconcile with, yet nothing works?”

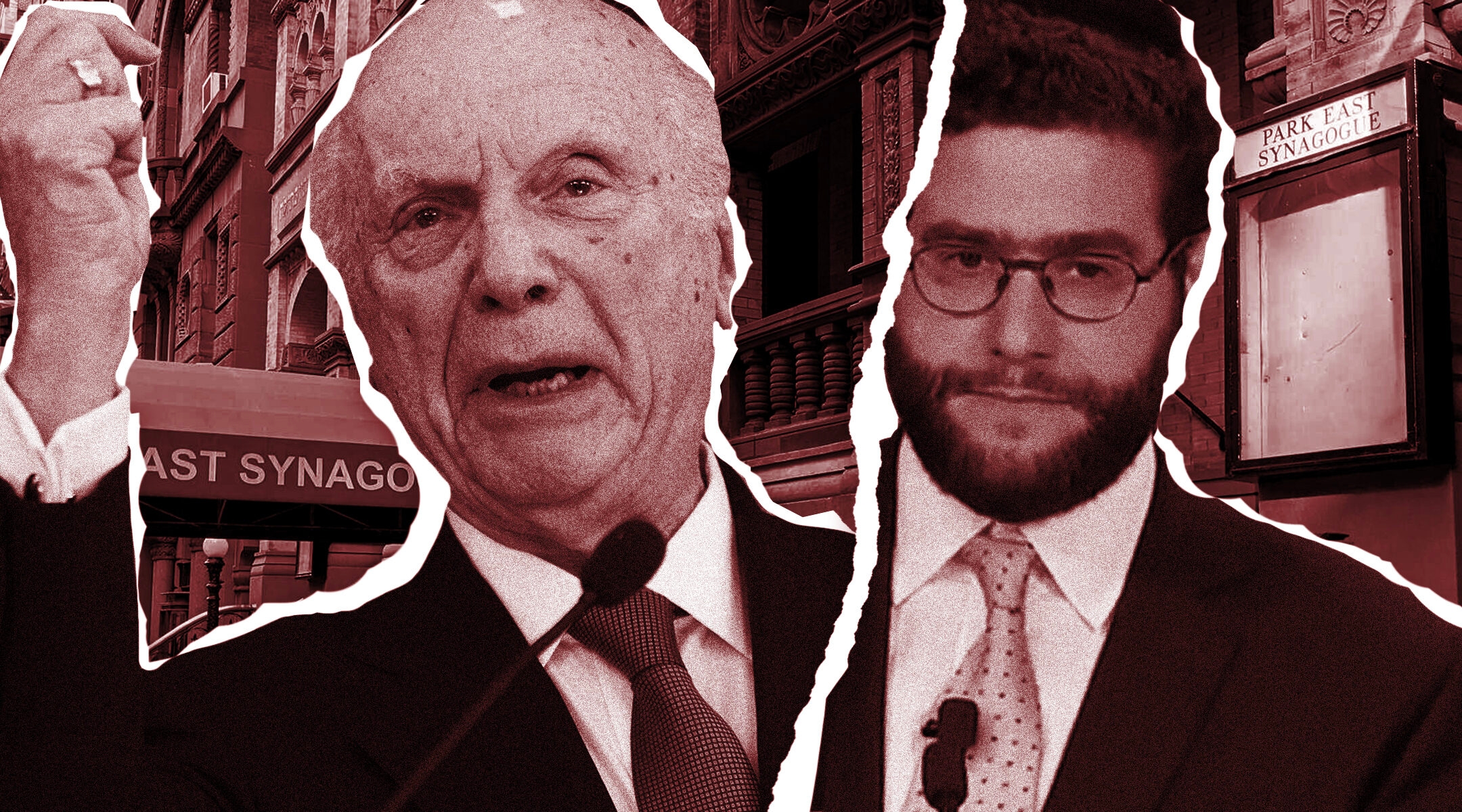

The sermon was about the biblical rivalry between the young David and the older Saul, but Goldschmidt delivered it after years of simmering tensions with his synagogue’s senior rabbi, the 91-year-old Arthur Schneier. The two had split over the terms of Goldschmidt’s employment, his work with younger members — and even the safety of the apartment the synagogue provided him.

Five weeks later, that tension would escalate to a rupture: In mid-October, Goldschmidt, 34, was fired from his job as assistant rabbi of the vaunted Park East Synagogue on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, after a decade with the congregation. He and his wife, who is pregnant, pulled their children out of the school affiliated with the synagogue.

Goldschmidt’s relationship with Park East has been “permanently severed,” Park East’s board president said in a letter to members.

The abrupt firing has divided the monied Orthodox community; Schneier supporters and Goldschmidt supporters have launched dueling petitions. It has also drawn attention to the unusual leadership structure at Park East, in which Schneier, who is among the oldest pulpit rabbis in the United States, serves full-time while also drawing a salary from the foundation he runs — all without an apparent succession plan in place.

Both Schneier and Goldschmidt declined to speak with the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Goldschmidt’s supporters say he is a talented rabbi who was popular with younger members and has been mistreated with too little explanation. Schneier’s allies, meanwhile, say Goldschmidt had sharply misjudged his status in the congregation and had erred by “attempting, effectively, a coup” against Schneier, a Holocaust survivor famous for his human rights activism who has cultivated relationships with some of the world’s most powerful people.

“When he surmised he was not going to be the rabbi, or that was not in the cards for him, that he did not have the stature, the education or the qualifications, he attacked the man who gave him the opportunity in the first place,” Hank Sheinkopf, the veteran political strategist who has stepped in as Schneier’s spokesman, said about Goldschmidt. “You have an irresponsible, unacceptable, childish response to a set of facts.”

That response includes potential legal action: Hours after Goldschmidt was fired, his lawyer sent a letter protesting the decision and threatening to take the synagogue to court.

But the more pressing issue for the synagogue may be how it addresses the fact that its world-famous rabbi, while “a very spry 91,” according to one leader, appears not to have cultivated a successor.

“Everyone knows that Rabbi Schneier is getting old and has begun to think about the plan for the future,” one involved member told JTA. But what that plan might be is unclear — beyond the fact that the community’s 10-year former apprentice will play no role.

Everything about Park East Synagogue broadcasts prestige. Its Byzantine architectural facade, complete with a row of arches and a rose window, has earned it landmark status in New York City and a spot on the National Register of Historic Places. Its calendar is punctuated with events featuring Important People — such as, on consecutive days this coming November, the French Jewish philosopher Bernard-Henri Levy and the consul general of Austria. Those familiar with the synagogue say it sees itself as an institution as well as a congregation — if not more the former.

Park East Synagogue (Ben Sales)

Cultivating important people, and being in important places, has been a defining theme of Schneier’s six-decade-and-counting career. Park East was located across the street from what was then the Soviet Mission in New York and in 1965, three years after becoming Park East’s rabbi, Schneier printed a full-page ad in The New York Times with the signatures of Sen. Robert Kennedy and other leading officials announcing a protest in front of the mission (and synagogue) on behalf of Soviet Jews.

That effort morphed into the Appeal of Conscience Foundation, led by Schneier, which went on to advocate for Soviet Jews and for peace in other conflict zones. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, it was particularly active in efforts to bring peace to the Balkans in the 1990s. Schneier has spoken at a long list of international venues, including the U.N., where he was appointed U.S. alternate representative in 1988.

According to last year’s tax documents, Schneier received $200,000 in compensation from the foundation, which is run by his daughter, who received a similar salary. Another column of the document lists $400,000 in “other compensation from the organization and related organizations.”

Schneier’s activism has raised the stature of his synagogue, which became the first in the history of the United States to host a pope, Benedict XVI, in 2008. The next year, it hosted Eastern Orthodox Patriarch Bartholomew.

Along the way, Schneier also founded a Jewish day school that shares space with the synagogue — and is named after him.

Rabbi Arthur Schneier speaks at Park East Synagogue in New York City, March 3, 2017. (Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

A virtual celebration of Schneier’s birthday last year, a few months into the pandemic, attracted tributes from a long list of prominent figures including both living popes, the patriarch, the United Nations secretary general, President Donald Trump, future President Joe Biden, Israel’s president, Israel’s prime minister, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and more. According to a graphic attached to a video of the party, Park East appears to have raised more than $1 million at the event, which doubled as a 130th anniversary party for the synagogue.

When Goldschmidt entered Park East as a rabbinic intern a decade ago after studying at well-regarded Haredi Orthodox yeshivas in Israel and Lakewood, New Jersey, he came in with connections of his own. He is the son of Rabbi Pinchas Goldschmidt, who has been the chief rabbi of Moscow for nearly three decades. The elder Goldschmidt, who was born in Switzerland, is also the president of the European Conference of Rabbis, and has also been able to manage relationships with powerful people. He is known for being close with Merkel and, despite that, has mostly been able to maintain his position in Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

By 2012, Benjamin Goldschmidt was Park East’s assistant rabbi, and focused his work on two overlapping constituencies — young families and Russian-speaking Jews. Until he was fired, he ran the Sunday Shkola, an education program for Russian-Jewish children. For a brief period between April and May of 2021, he also ran the NextGen Minyan, a prayer service for young professionals that shut down over the summer and then was reopened recently without Goldschmidt at its head.

He also built a public profile, publishing essays in the Washington Post and Israeli publications. Before arriving at Park East, he studied at Ponevezh Yeshiva, a prominent haredi yeshiva in Bnei Brak, Israel, and has been a contributor to Kikar HaShabbat, a haredi Israeli news site. In 2014, he married the journalist Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt in a wedding that was featured in The New York Times’ “Vows” column.

But in the years after the wedding, the relationship between senior and assistant rabbi frayed. Goldschmidt was never given a contract at Park East, and was never guaranteed vacation time or severance pay. Matters came to a head in early 2020 surrounding the rented apartment that Park East traditionally provides to the assistant rabbi.

By that year, the apartment provided to the Goldschmidts was in disrepair — including months of infestation — and they asked the synagogue for help finding a new place, which was not forthcoming. (Sheinkopf responded that in rental units, the tenants are responsible for handling maintenance issues. “Pick up the phone, call the super,” he said. “The synagogue isn’t responsible for a rental property, he is.”)

They ended up moving out, bouncing between hotel rooms and crashing with friends and family, until friends chipped in to rent them a new unit in the neighborhood. That decision has ended up being a boon to Goldschmidt and his family, as they can remain in their home even after his termination.

Schneier’s 90th birthday presentation in June 2020 reflected the strained ties between the rabbis. The 92-minute video produced in honor of Schneier featured tributes from a string of prominent rabbis around the world — including Goldschmidt’s father — but Goldschmidt himself was not invited to deliver one. He was thanked for his efforts during the pandemic, including conducting funerals alone during peak COVID, via a message that appeared on screen, well more than an hour in, for six seconds.

People close to Schneier say that Goldschmidt was never in the running to lead the synagogue after Schneier. They say Goldschmidt doesn’t have the leadership and fundraising chops necessary to lead the synagogue. A few people noted to JTA, unprompted, that Goldschmidt doesn’t have a bachelor’s degree, which they view as disqualifying.

He stayed at the synagogue for a decade, they claim, due to a mix of inertia, goodwill and the daunting nature of finding a replacement during the pandemic.

“He has no experience running a large institution, he has no experience raising the needed funds that are required, he does not have an appropriate education, the man does not have a bachelor’s degree,” Sheinkopf said.

Schneier’s backers, including Sheinkopf, are also adamant that the rabbi’s son, Rabbi Marc Schneier, is “absolutely not” being considered for the job. The younger Rabbi Schneier also caters to wealthy Jews — he founded the Hampton Synagogue — and has also parlayed his rabbinate into international activism. He’s an advisor to the king of Bahrain and works to promote ties between Jews and Muslims. He’s also drawn the attention of the New York Post’s Page Six for his string of marriages and divorces, in some cases to his congregants.

Marc Schneier showed up at Park East for services recently, but Schneier’s backers say that was only to support his father.

“Marc Schneier is not interested in being the rabbi of Park East Synagogue,” Sheinkopf said. “He’s quite successful and happy in Westhampton, in a congregation that continues to grow. The rumors to that effect are absolutely inaccurate.”

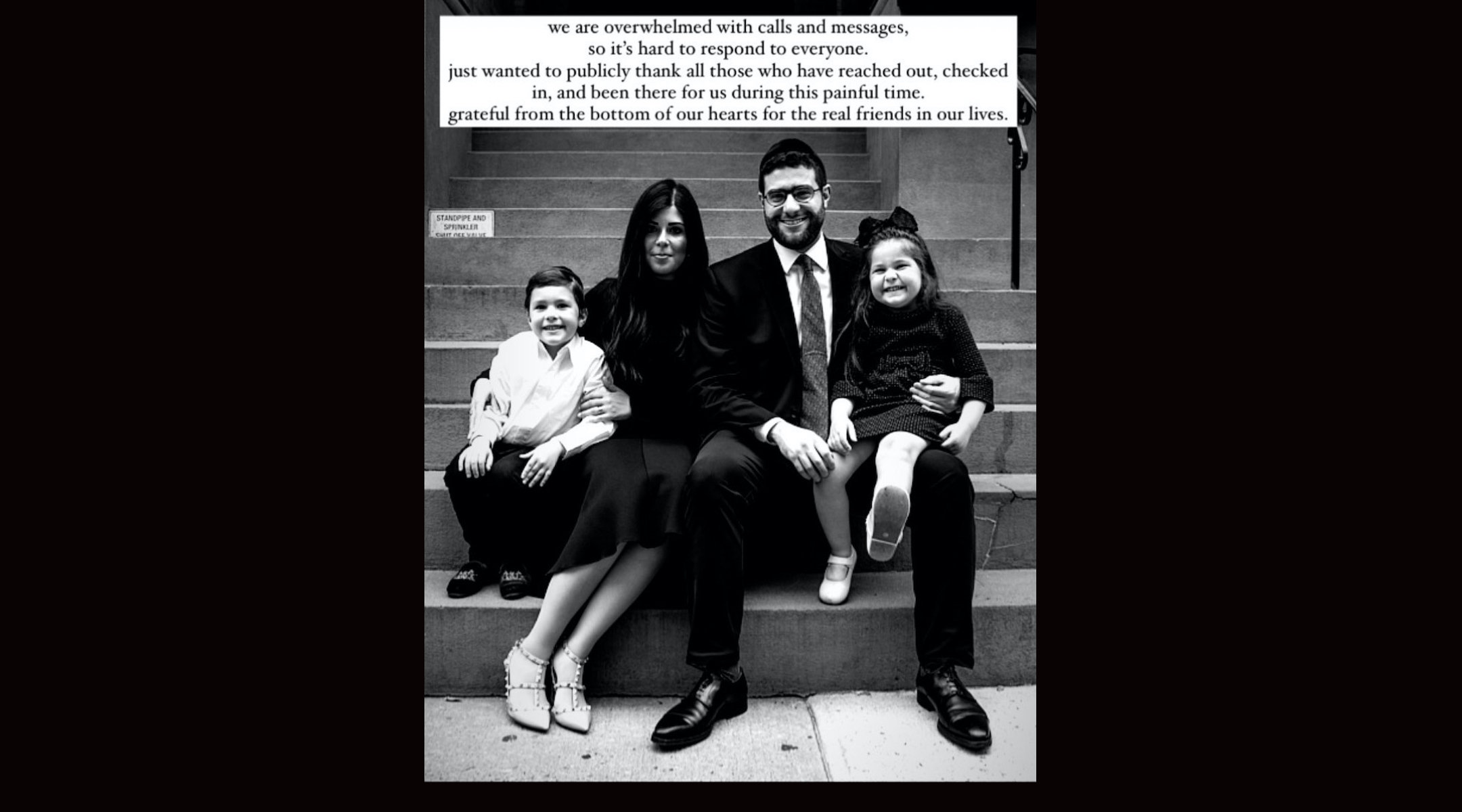

Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt posted a thank-you note to “all those who have reached out, checked in, and been there for us during this painful time” on Oct. 24, 2021, nine days after her husband, Rabbi Benjamin Goldschmidt, was fired from his job at Park East Synagogue. (Screenshot from Instagram)

In fact, despite Schneier’s advanced age, it seems like there wasn’t a succession plan at all until Goldschmidt was fired. That may have been one of the triggers for the chain of events, conducted in large part via email, that led to the firing in the first place.

On Oct. 8, four men, led by Brad Colman and Brian Kaufman, sent an email to the entire synagogue membership calling for a change of course at Park East. The email opened with a paragraph praising Schneier and his career, as well as “his story, his survival, his commitment and the spirit that he brings to daily Jewish life.”

What followed was less complimentary. The writers said that they were concerned about the future of the synagogue and that “while Shabbat services used to bring in several hundred worshippers, now they bring in far smaller numbers, with few younger individuals and families (unless there is a special event).”

The email announced the formation of a committee “to revitalize the synagogue and build a sustainable future.” The committee proposed to work with Schneier, Goldschmidt and the board of trustees.

Allies of Schneier claim that neither Schneier nor the board of trustees knew about this committee. Two days after the email went out, members began to complain. One person sent an email to the would-be committee co-chairs, accusing them of having “misappropriated my confidential information.” He added, “I reserve my legal rights to protect the confidentiality of my information and will hold you accountable for any damage that results from its theft.”

Colman and Kaufman have not responded to a request for comment. But four days after sending the email, they began to do damage control. In an email sent to Schneier and the board, they wrote, “we want Rabbi Schneier to be Senior Rabbi of Park East Synagogue for life. Rabbi Schneier has served this community for six decades and we have no desire or intention of making changes to the Rabbinic leadership of the synagogue.” The phrase “for life” was underlined.

But they added, without offering details, that they had “heard for many years of the synagogue’s financial challenges,” and quoted an email they had received saying that the community was “at risk.” In the email, sent to a board composed largely of older men who are allies of Schneier and unelected by the congregation, they wrote that they wanted to “hear from all members (young and old).”

To Schneier and his allies, these emails constituted an act of brazen insubordination — and the board blamed Goldschmidt. In an email to the synagogue membership sent on Friday, Oct. 22, Board President Herman Hochberg described the Schneier camp’s view of events.

According to Hochberg, on Oct. 10, Schneier and Hochberg met with Goldschmidt, who had provided the members’ email list.

Hochberg claimed that Goldschmidt then “refused to apologize for his rogue actions. In fact, he further enflamed the concerns of Rabbi Schneier and myself by additionally stating that he would continue to use and disseminate the list at his discretion.” Hochberg also wrote that the people who wrote the Oct. 8 email “are neither trustees, nor actively involved in the Synagogue or the Rabbi Arthur Schneier Park East Day School.”

Five days later, the Park East board met via videoconference and voted unanimously, on Schneier’s recommendation, to fire Goldschmidt. A few days after that, Schneier sent a letter to congregants defending his record and attacking the emails from supporters of Goldschmidt.

“Surprisingly, no signatory of the letters ever approached me or any of the Trustees about the initiatives they had in mind,” he wrote regarding the Oct. 8 email. “I suspect it is because they have no real ideas beyond what we ourselves are already doing and that there are other motives afoot that I will not dignify in this letter to you, my beloved congregation.”

But Goldschmidt might fight back. The day Goldschmidt was fired, Daniel Kurtz, a lawyer working in support of Goldschmidt, sent a letter to a member of the Park East board arguing that, according to state law, only the synagogue members themselves have the authority to fire Goldschmidt. Kurtz wrote that if Goldschmidt is prevented from returning to his job, the synagogue “will be met with swift legal action and a wrongful termination lawsuit.” Kurtz declined to comment when reached by JTA.

But even if Goldschmidt provided the list of emails, he may not have broken the law. Synagogues often share contact information with members, and New York State’s Not-for-Profit Corporation Law says that any member of an organization has the “right to examine [a] list or record of members and to make extracts therefrom.”

And his supporters have since mobilized to defend him. Days after he was fired, a petition went online saying signatories were “shocked and disheartened” to learn of his firing. As of Oct. 26, it has more than 400 signatures. A competing petition, titled “Stand with Rabbi Schneier,” has 44.

“If I were bringing young children into the Upper East Side right now, I would have hoped that an individual like Rabbi Goldschmidt would be an assistant rabbi at an institution like Park East,” an engaged Park East member in his 40s told JTA. “What he’s done, his outreach, his individual support, his knowledge of members, his respectfulness and candor — he never complained about anything.”

Supporters of Schneier paint a different picture: One of a rabbi with limited appeal among young families who was unqualified for the job, and nonetheless made an ill-advised grab for it. A common refrain among Schneier’s defenders who spoke to JTA is that Goldschmidt’s supporters weren’t really involved in the congregation, though a recent congregational newsletter does congratulate one of them on a happy occasion and notes the family’s affiliation.

“What happened here is an unfortunate case of a junior rabbi attempting, effectively, a coup to attain the position that he coveted from Rabbi Schneier,” said a congregant with knowledge of the situation. “Rabbi Goldschmidt was happy having a small loyal cohort of congregants, he would schmooze, but when it came to going out and performing the duties alongside Rabbi Schneier he was really a shrinking violet.”

According to the member of the synagogue leadership, Goldschmidt in fact assumed a larger set of duties during the pandemic, officiating more while Schneier was limited in his activity due to his age. And Goldschmidt’s wife has repeatedly written about his increased responsibilities over the past year and a half. In May 2020, after COVID had raged for weeks through New York City, she wrote that he officiated at a series of funerals, checked up on congregants and taught Zoom classes.

But the member of the synagogue leadership was still blunt when describing Goldschmidt’s reaction to being fired.

“What’s happened here — I’m not saying he’s like Trump, I’m not — but there’s a little Trump here, where he can’t accept being fired because it happened so quickly,” he said. “I think what’s happened here is he needs it to be said that he shouldn’t have been fired, or to fire him was wrong, because he can’t accept it.”

Regardless of what occurred, Goldschmidt appears to retain a base of support. One signatory on the pro-Goldschmidt petition wrote, “the Goldschmidts are exactly what Park East Synagogue requires. It’s both disheartening and shocking to [see] them being treated this way.”

Goldschmidt’s father, Rabbi Pinchas Goldschmidt, hasn’t commented on the affair. But last week, he did share someone else’s tweet about his son being fired.

It said, “Shame on those cowards who so brazenly sacrifice our Jewish communities on the altars they’ve erected to their own fragile egos.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.