(JTA) — Occult practices and totems are a mainstay of Halloween season, and sage bundles, altars and crystals are an increasingly trendy way to dabble in divination and witchcraft. But the spooky supernatural world also has a long history in Judaism, and modern “Jewitches” are encouraging the connection — though their practices often slightly differ from their non-Jewish contemporaries.

“I do not burn sage,” said Zo Jacobi, who runs Jewitches, a popular blog and podcast that deep dives into ancient Jewish myths and folkloric practices. The sage-related ritual of “smudging,” an Indigenous ceremony popular among modern witches for cleansing a person or place of negative energy, “is not a Jewish practice,” she said. “But Jews had crystals. Actually, they were called ‘gems.’”

Jacobi and her peers are revitalizing ancient Jewish practices of witchcraft, which have been seeing something of a revival as of late. Far from having an uneasy relationship with magic practitioners, Judaism — or at least Kabbalistic strands of it — has long embraced them.

Jacobi, based in Los Angeles, studies those gems’ role in Jewish ritual, along with the connections between assorted other magical artifacts and Judaica. Eight shelves in her home are filled with books on Judaism as well as Jewish magic, witchcraft and folklore.

Her studies have revealed the historical ways that items like gems have been used in Jewish magical correspondences. Like healing crystals, gems are meant to protect and heal based on their properties, according to Midrash (Numbers Rabbah 2:7). For example, sapphire was thought to strengthen eyesight.

“It’s in a medieval text called the ‘Sefer Ha-Gematriaot,’” Jacobi said. “But even if we go to the Torah, we see crystals on the breastplates of the kohanim (high priests of Israel).”

Many Jewish rituals today have their roots in warding off demons, ghosts and other mythological creatures. When we break glass at a wedding, scholars say, we’re not just remembering the destruction of the Temple; we’re also scaring off evil spirits that may want to hurt the bride and groom. Likewise, ancient Jews believed that the mezuzah protected them from messengers of evil — a function parallel to that of an amulet, or good-luck charm.

“The mezuzah is absolutely an amulet,” said Rebekah Erev, a Jewish feminist artist, activist and kohenet (Hebrew priestexx, a gender-neutral term for “priest” or “priestess”) who uses the pronouns they/them and teaches online courses on Jewish magic. “I consider it to be a reminder of the presence of spirit, of goddess, of shechinah [the dwelling or settling of the divine presence of God]. Much of magic is about reminding ourselves that we’re all connected and that everything is alive and animate.”

The moniker “Jewitch” itself can be seen as controversial within the group. Erev first heard the term while attending a 2014 “Jewitch Collective” retreat in the Bay Area.

“I feel that any word that identifies someone as a witch is controversial in nature because of how society, including Jewish society, has demonized witches leading to violence and ostracizing,” Erev said. “To be a Jew and to be a witch has had serious repercussions throughout time. I hope the recent popularity of the term ‘Jewitch’ will bring more acceptance and understanding of both identities and help to make our practices more widely accessible.”

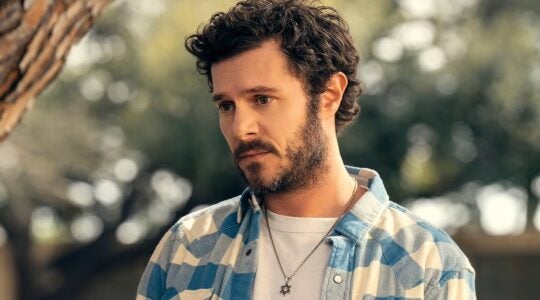

Priestexx Rebekah Erev calls the mezuzah an amulet. (Vito Valera)

“I feel that any word that identifies someone as a witch is controversial in nature because of how society, including Jewish society, has demonized witches leading to violence and ostracizing,” they said, even though they do consider both witchcraft and Judaism to be major tenets of their life.

Cooper Kaminsky, a Denver-based intuitive artist and healer, concurred that the portmanteau was “revisionist” to some, but added, “Many, including myself, are empowered by identifying as a Jewitch.”

Historically, as Judaic practices grew more patriarchal, women were exempt from studying the Talmud and Torah. They knew little Hebrew, so they created their own prayers in Yiddish, used herbal remedies and centered their religious practices around the earth.

Erev mirrors these customs by creating magical rituals, like meditating on cinnamon sticks during the month of Shvat, hearkening back to how cinnamon trees in Jerusalem scented the land during the harvest.

“There’s a Kabbalistic idea of making oneself smaller for creation to emerge. Connecting with a cinnamon stick is a simple ritual. The cinnamon folds in, and the bark contracts in on itself,” Erev said. “Sometimes contracting inward can give us space to emerge and create.”

They also do spellwork, creating spells for new love, pregnancy protection and social justice; on their blog, they shared an incantation designed to bring more awareness to Indigenous Land Back movements.

The goal of many “Jewitch” educators and practitioners, they say, is to shine a light on rituals that have been forgotten or buried for self-preservation. Jacobi believes that many folkloric practices died out following the 13th-18th centuries because, at the time, Jews were viewed as demonic witches.

“Jewish communities did what they thought would protect them from literal certain death. Some of that came at the expense of some of these practices,” Jacobi said. “Instead of the supernatural reasons, they tried to give rational reasons for what they were doing. Ashkenazi Jews routinely tried to debate with their oppressors in the hopes that they could out-logic antisemitism.”

This traumatic history, the Jewitches say, is often papered over or dismissed as “myths” and “superstitions.” “Saying ‘superstition’ is a way that we downplay our magic,” Kaminsky said. “We protect ourselves because, historically, a huge part of our oppression has been because we’re magical.”

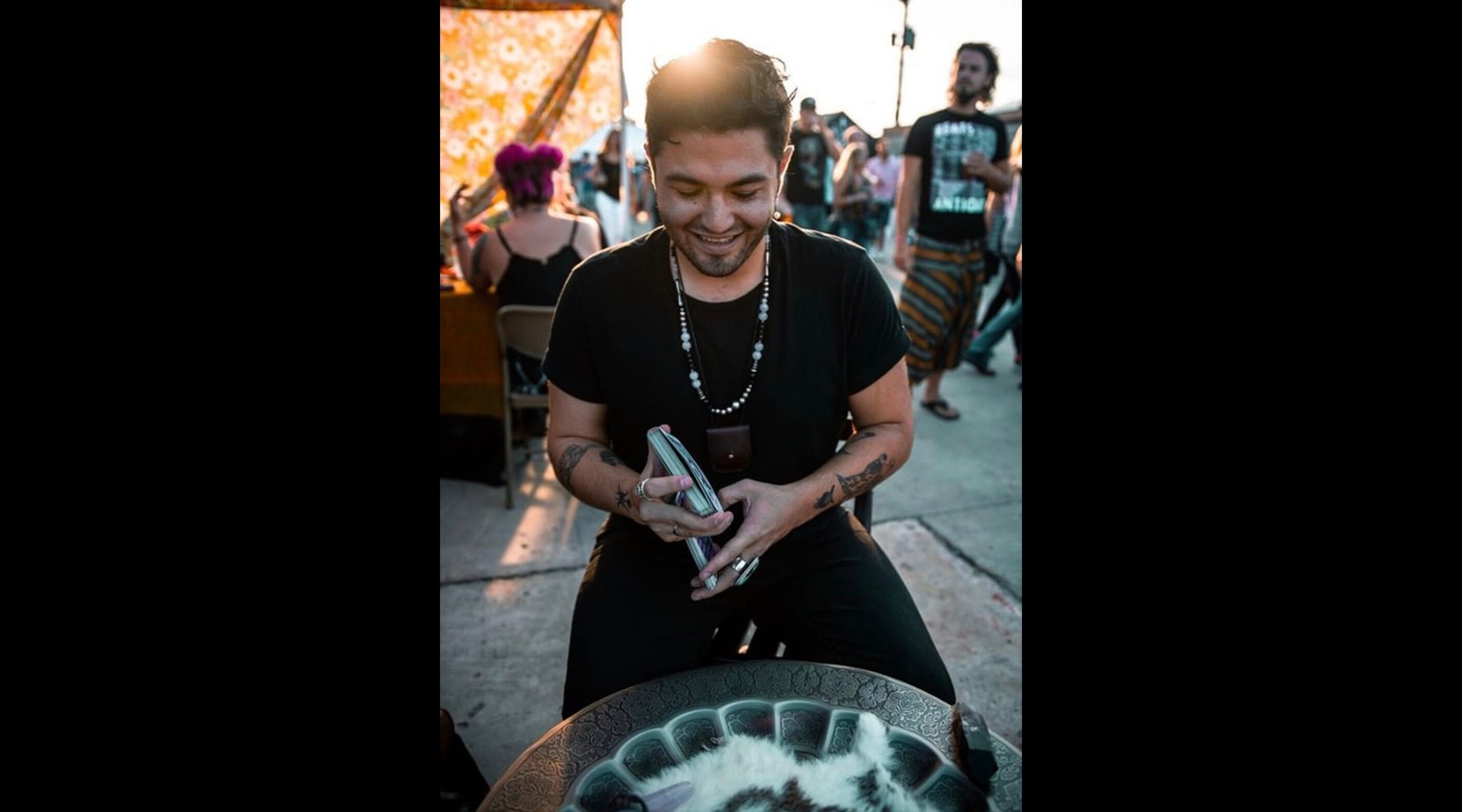

“Almost all of our Jewish spells are for the sake of healing,” says Cooper Kaminsky. (Colin Lloyd)

Kaminsky, who uses the pronouns they/them, does spiritual readings for clients that draw upon Kabbalah, Tarot and the Akashic records — a reference library of everything that has ever happened, which spiritual mediums believe resides in another dimension. Kaminsky incorporates Jewish prayers into their spellwork, like reciting the Psalms of David when doing candle spells and the B’sheim Hashem as a magical invocation.

Kaminsky, who uses the pronouns they/them, grew up in a Conservative Jewish household and learned the basic concepts of Kabbalah in Jewish day school.

“Kabbalah looks at Judaism through a cosmic, mystical lens that clicked for me a lot more than looking at a story from the Torah,” Kaminsky said. “As I read more Kabbalah, I started feeling more connected to my Judaism.”

Various scholars and rabbis have linked Kabbalah to Tarot, a deck of cards originally used in the mid-15th century to play games that evolved to divinatory practices in the 18th century (though Jacobi, for one, refutes this idea, claiming the connection has never been proven). The Tarot’s Major Arcana — the trump cards of the deck, which detail the evolution of one’s soul — usually make up 22 cards in any given pack, a meaningful Jewish number: the same as the number of letters in the aleph-bet, and the number of pathways on the Kabbalistic Tree of Life.

For their energy work, Kaminsky draws parallels between the chakras, energy points in the body discussed in Hinduism, and the Kabbalistic Tree of Life.

“The Tree of Life is an energy network,” they said. “There’s the meridians of energy, and the chakras are like the middle pillar.”

Mystical practices were a part of Jacobi’s upbringing. Her parents practiced Kabbalah, metaphysics, folklore and folk mythology. They have attended the same local Chabad since Jacobi was three years old.

Thanks to these experiences, Jacobi is comfortable living out of the (broom) closet — a tongue-in-cheek term that some modern witches use to refer to openly practicing witchcraft. She grew up with astrology, used tarot cards on Shabbat and played with her mother’s rose quartz crystal ball while her father led Havdalah prayers. The Jewitches blog and podcast are filled with mythological creatures with origins in Jewish beliefs, like dybbuks, werewolves, dragons and vampires.

Some creatures are unique to Jewish lore: the vampiric Alukah, a blood-sucking witch referred to in Proverbs 30, turned out to be Lilith’s daughter, while a Broxa originated as a bird from medieval Portugal that drank goat’s milk and sometimes human blood during the night.

“Whenever there have been dire times throughout history, people have turned to mysticism; that’s how Kabbalah emerged,” Erev said. “We need to look to our ancestors for guidance. There are a lot of tools in our human community for healing and re-dreaming and creating a world that is safe and generative for all beings.”

Kaminsky thinks magic has the power to repair the world: “Almost all of our Jewish spells are for the sake of healing. Tikkun olam, using our magic to repair the world, is beautiful.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.