(JTA) — As a writer, literature professor and one of the 82% of U.S. Jews who report that “caring about Israel” is either “essential” or “important” to their Jewish identity, I am pained when I see authors whom I admire launch exaggerated or misinformed attacks on Israel.

But I also take solace in a correspondence, celebrated in a new children’s book, that showed how one Jewish reader engaged an author who she felt trafficked in anti-Jewish tropes. That the correspondence took place in the 19th century, and the author in question is Charles Dickens, does not make its lessons any less timely.

I was distressed when Irish novelist Sally Rooney said Tuesday that she wouldn’t allow her latest novel to be published in Hebrew by an Israeli publisher “that does not publicly distance itself from apartheid and support the UN-stipulated rights of the Palestinian people.”

Saddened but not surprised: Earlier this year, Rooney signed a “Letter Against Apartheid” — a text issued in the wake of the latest round of violence between Israel and Hamas. It called for governments to “cut trade, economic, and cultural relations” with the Jewish state, which it said had committed “ethnic cleansing,” “massacres” and more in its response to the thousands of rockets fired into Israel by Hamas.

With their particular focus on words, writers should do better, especially when they organize, join or promote such endeavors. If their misrepresentations are without malicious intent, they’re in desperate need of further education.

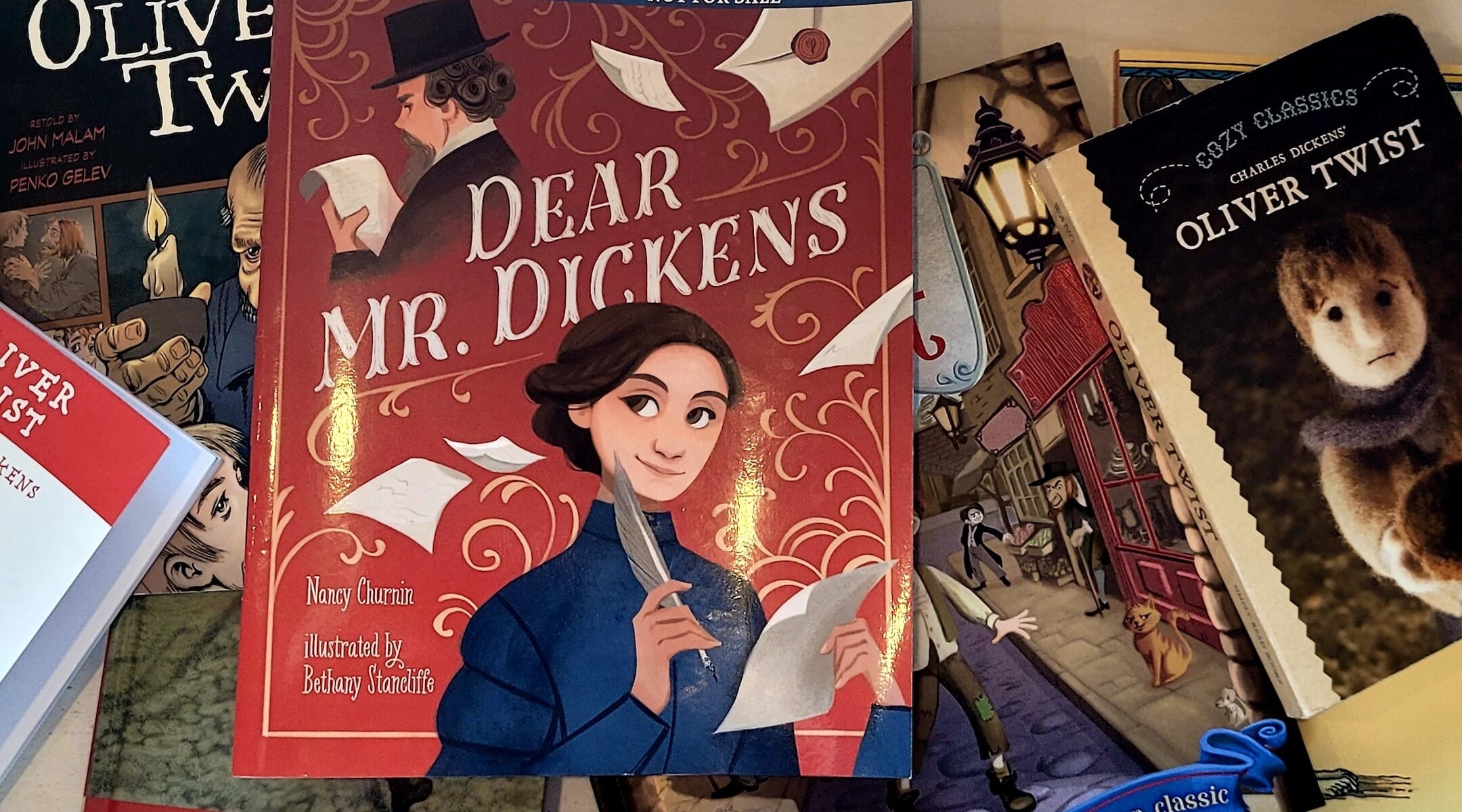

How such “education” might best be carried out is the subject of “Dear Mr. Dickens,” a new picture book written by Nancy Churnin and illustrated by Bethany Stancliffe. This true story of correspondence between the celebrated author and a reader named Eliza Davis — a Jewish woman who launched the exchange to protest antisemitic tropes in “Oliver Twist” — imparts a timeless lesson about speaking out against injustice.

(Disclosure: Churnin and I currently belong to the same writers group; I hadn’t seen this manuscript before being granted pre-publication electronic access to an advance review copy.)

Davis (1817-1903) refused to be daunted when writing the famous author, whose portrayal of “the Jew” Fagin in “Oliver Twist” landed “like a hammer on [her] heart,” as Churnin describes it. Davis lacked Dickens’s stature. But “she had the same three things that [he] had: a pen, paper, and something to say.” Quoting the correspondence, Churnin conveys Davis’s message: Fagin “encouraged ‘a vile prejudice’” against her people. According to Churnin, Davis had considered Dickens especially heroic — and the Fagin character especially discordant — because Dickens “used the power of his pen to help others.”

In response, Dickens declared that Fagin was based on real-life Jewish criminals. In a mix of what we’d today call gaslighting and mansplaining, he went further: “Any Jewish people who thought him unfair or unkind — and that included Eliza! — were not ‘sensible’ or ‘just’ or ‘good tempered,’” Churnin relates. Davis tried again; evidently, Dickens didn’t write back.

But the Jewish character in his next novel — the estimable Mr. Riah in “My Mutual Friend” — was no Fagin.

After that novel appeared, Davis thanked Dickens for “‘a great compliment paid to myself and to my people.’” This time, Dickens responded much more warmly. He went further, notably in a magazine essay in which he referred to Jews as “an earnest, methodical, aspiring people” and in changes to a subsequent printing of “Oliver Twist,” when he instructed the printer to remove many instances in which he referred to “the Jew” and to use Fagin’s name instead.

There’s still another aspect of Eliza Davis’s story that resonates: Instead of calling Dickens out publicly, Davis approached him one-to-one.

True, they weren’t strangers. According to an author’s note, the Davises had purchased Dickens’s former home a few years before this correspondence began. But Eliza Davis didn’t know how Dickens would receive her initial message. And when he scathingly dismissed it, she didn’t give up.

Rudine Sims-Bishop speaks of books as “windows” and “mirrors” for the children who read them. With rising antisemitism in the United States and elsewhere, “Dear Mr. Dickens” is a sadly timely mirror for Jewish children; importantly, it provides a positive, action-oriented message of tikkun olam, or the Jewish value of repairing the world. For others, the book offers a window into Jewish experience, alongside that universal message about confronting injustice with written words.

Moreover, Eliza Davis’s reaction to Dickens’s words — her sense of betrayal by an admired author whose compassion somehow didn’t extend to Jews — mirrors my own increasingly frequent experience. Like so many Jews, I am imbued with a sense of klal Yisrael, “Jewish peoplehood,” linking us with Jews everywhere — including in Israel, the world’s only Jewish state, where nearly half of the world’s Jews now live.

This doesn’t mean that I support all Israeli policies. But criticism of Israel needs to be leavened by facts and context, and a recognition that the situation is far more complex than declarations of an “apartheid” regime and “ethnic cleansing” suggest.

Although I’ve gone the public route from time to time, private communications with writer-friends and acquaintances — especially in the wake of the May 2021 war between Israel and Hamas — have proven far more fruitful, yielding corrections, deletions and other changes.

For which I, like Davis, have expressed thanks.

I don’t expect “great compliments to me and to my people” from authorial idols and colleagues, particularly those of Palestinian descent. All I’m seeking is fairness — and freedom from vile prejudice.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.