(JTA) — During a visit to his native Libya in 2002, David Gerbi saw something that he says still haunts him almost 20 years later.

“I was horrified to see children playing atop the ruins of the Tripoli Jewish cemetery, scampering about debris littered with human remains,” Gerbi, who left Libya many years ago for Italy, told the Behdrei Haredim news site in Israel last week.

The experience turned Gerbi into an advocate for what are known as heritage sites in his old community. But over the years, his efforts to preserve or restore communal Jewish sites in war-torn Libya, where no Jews remain, came to naught.

So Gerbi began to consider alternatives. And now, the psychologist who lives in Rome has announced a new effort to set up a virtual cemetery to replace each of the physical Jewish ones that have been devastated in his country of birth.

“Especially in Tripoli and Benghazi, the Jewish cemeteries were obliterated,” he told the news site. “So I decided to make a virtual cemetery for our loved ones buried in Libya.”

The virtual cemeteries will have sections for prominent rabbis and commemorative pages for victims of the Holocaust — hundreds of Libyan Jews died in concentration camps operated by Nazi-allied Italy — as well as other pages recalling the victims of three waves of pogroms, in 1945, 1948 and 1967, he said.

Users of the website will be able to virtually light memorial candles and dedicate Kaddish mourning prayers through the website interface, he said. “It will be a way to remember the dead of a community gone extinct,” Gerbi said.

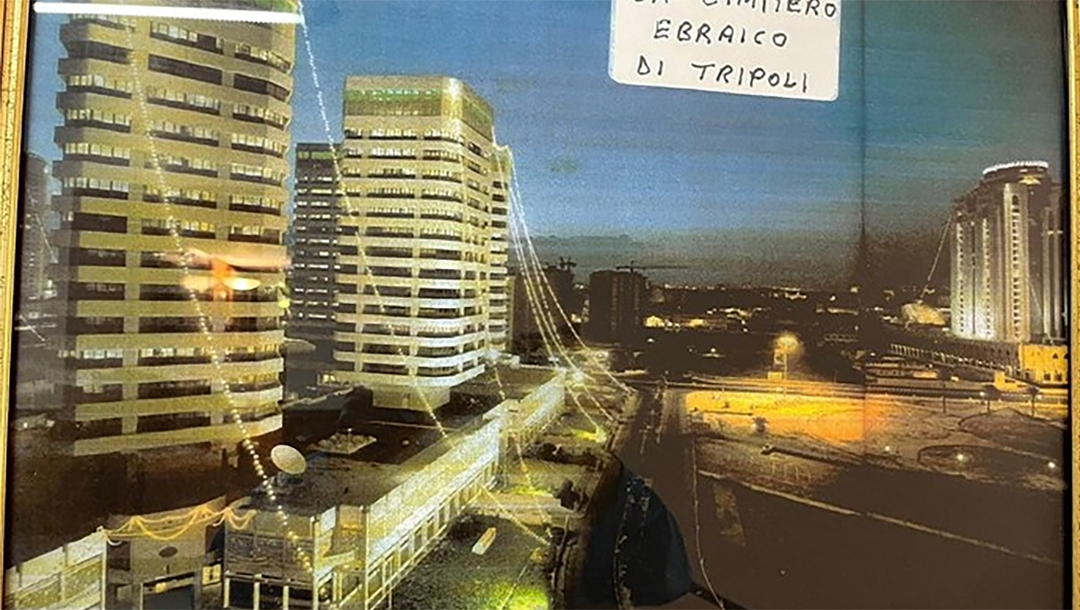

A high-rise building stands on what used to be the Jewish cemetery of Tripoli, Libya, in 2007. (David Gerbi)

The initiative is a collaboration with ANU: The Museum of the Jewish People in Tel Aviv, which seeks to document the experiences of Jews around the globe and over time. Together, they’re asking people with information about Jews buried in Libya to reach out.

Their effort is in line with other initiatives that aim to rebuild extinct Jewish communities online because their former homes are so inhospitable to restoration efforts, such as Diarna, a massive website that allows users to explore the cities in North Africa and the Middle East where Jews used to live.

Gerbi’s effort is narrower, focusing exclusively on the cemeteries of Libya, where, during World War II, 40,000 Jews lived in communities with a centuries-long history.

The Holocaust and the antisemitic policies of the independent Libyan government that followed, as well as hostility toward Jews by the local population, drove all of them out. By 2004, Libya did not have a single Jew residing in it, according to Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust museum.

Gerbi’s family was part of that migration. They fled Libya in 1967 when he was 12 years old, making them among the last Jews to leave the country. By 1969, the country had only 100 Jews.

The decades that followed, under the iron-fisted rule of dictator Muammar el-Qaddafi, offered few opportunities for preservation. But the central government collapsed after he was overthrown and executed in 2011, and the last decade has been marked by intermittent fighting among clans and militias with competing claims to leadership.

While those conditions have been harsh for Libyans, Gerbi said he hopes the shakeup could eventually give rise to a government that would be willing to address the country’s Jewish history and possibly normalize relations with Israel, as other Arab nations in the region have done in the last year. But he knows that could take many years, and he has essentially given up hope of having officials facilitate physical restoration work in the near future, Gerbi told Behadrei Haredim.

And the situation of those sites was poor even before Libya erupted into civil war, he said.

David Gerbi speaks about Libya in Johannesburg, South Africa, March 15, 2011. (The Times/Gallo Images/Getty Images)

It’s been 19 years since his visit to Tripoli’s Jewish cemetery but “the gruesome sights and chilling images I saw won’t let go of me,” he said. In 2007, Gerbi visited the site again, he said, “and I was shocked to discover that even the debris had been cleared out. They built a highway on the ruins of the Jewish cemetery and high-rise buildings. There’s isn’t a shred left.”

In Benghazi, Gerbi saw a warehouse full of boxes with human remains stuffed into them haphazardly. They had been collected from another Jewish cemetery before it was destroyed, he said.

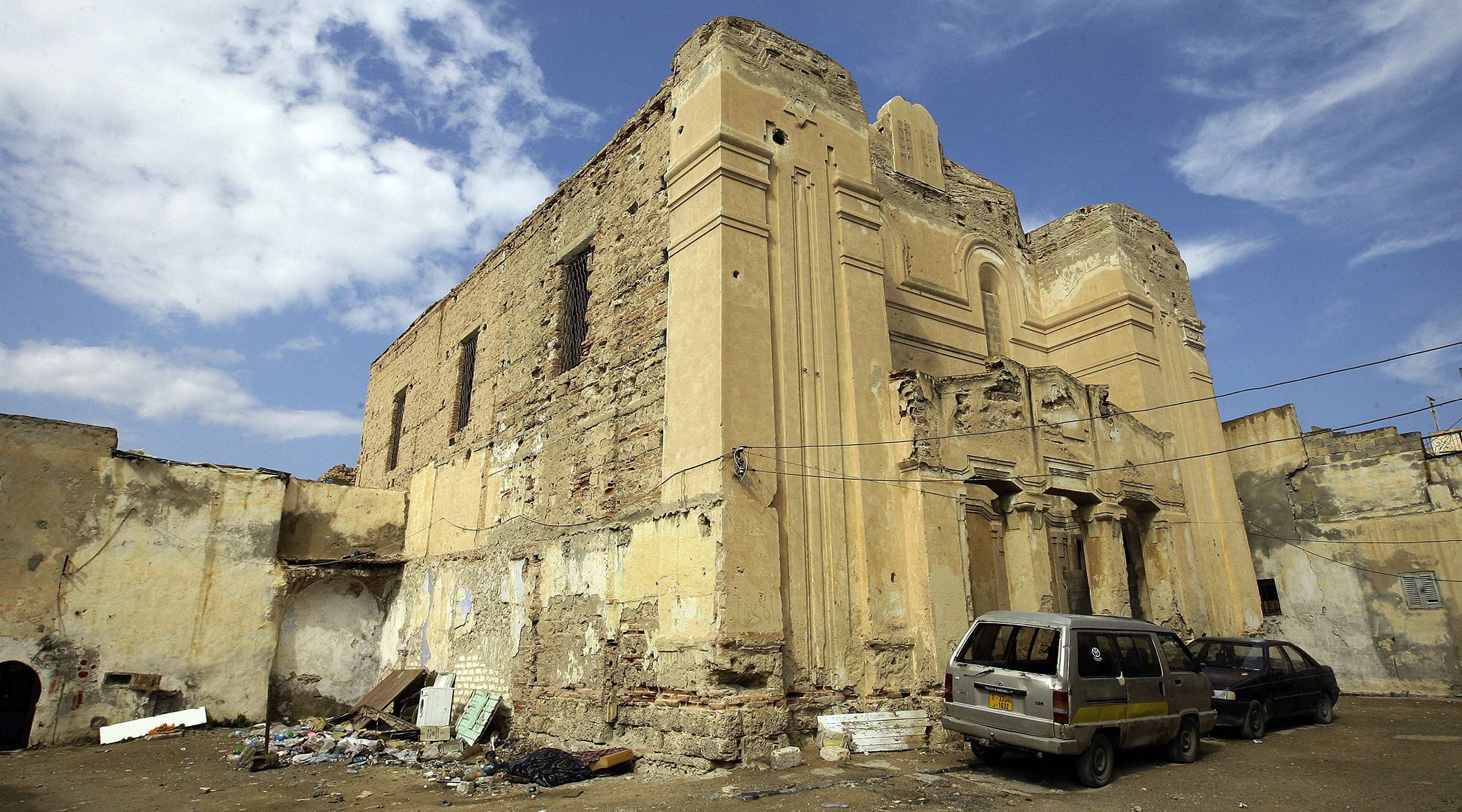

Old synagogues are also at risk, said Gerbi, a prominent member of the World Organization of the Jews of Libya, which promotes the interests of people whose families have roots in Libya.

Earlier this year, he told Italian media that an abandoned and ancient synagogue in Tripoli is being turned into an Islamic religious center without permission.

“The Sla Dar Bishi in Tripoli is in the hands of the local authorities (read: militias) since there is now no Jew living in Tripoli,” he told Moked, the Italian Jewish news site.

“It was decided to violate our property and our history,” he wrote. “The plan clearly is to take advantage of the chaos and our absence.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.