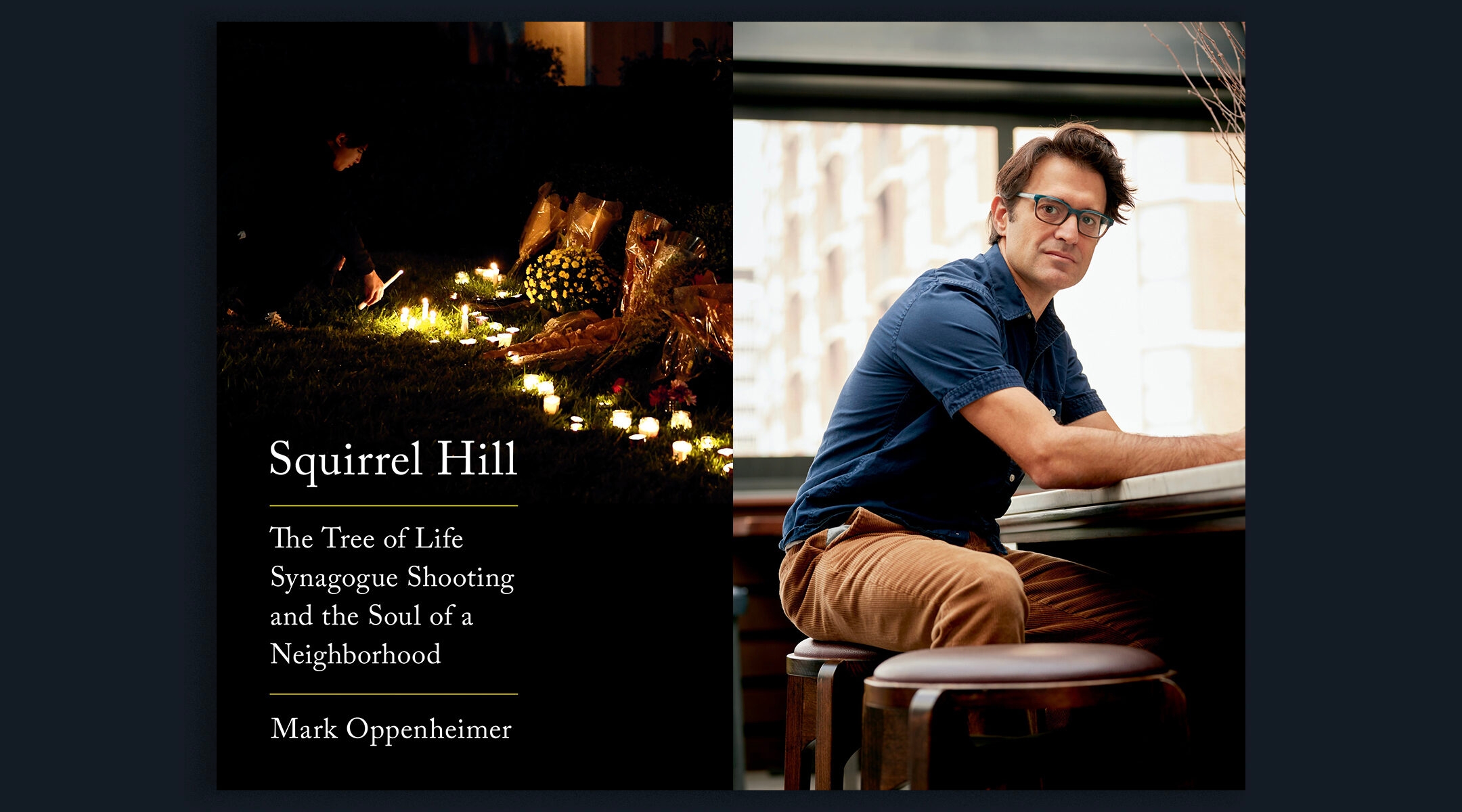

(Pittsburgh Jewish Chronicle via JTA) — Mark Oppenheimer’s new book, “Squirrel Hill: The Tree of Life Synagogue Shooting and the Soul of a Neighborhood,” recounts the deadliest antisemitic attack in U.S. history through interviews with those impacted — both directly and tangentially — by the shooting, while examining the effects of the event on Squirrel Hill, the heavily Jewish neighborhood of Pittsburgh where Tree of Life is located.

The author’s Pittsburgh Jewish roots go back several generations. His great-great-great grandfather co-founded the first Jewish burial society in Pittsburgh, and his father grew up on Aylesboro Avenue in the center of Squirrel Hill.

In writing his book, Oppenheimer traveled to the city 32 times, interviewed about 250 people and had contact with relatives of eight of the 11 people who were murdered that day. He also relied heavily on various news reports, including many published in the Pittsburgh Jewish Chronicle.

Oppenheimer is the host of Tablet magazine’s podcast “Unorthodox,” and is the author of five books, including “Knocking on Heaven’s Door: American Religion in the Age of Counterculture” and “The Newish Jewish Encyclopedia.” He was the religion columnist for The New York Times from 2010 to 2016.

Oppenheimer had a virtual conversation with the Chronicle to discuss the book prior to its release. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Pittsburgh Jewish Chronicle: Why did you decide to write this book now?

Oppenheimer: I was always curious about Squirrel Hill. The morning of the shooting, I was at a bat mitzvah in Newton, Massachusetts, with my eldest daughter. We had left our phones in the car until after the lunch. We got back to our car, I opened my phone, and I had a ton of messages. “Is everyone safe in Pittsburgh? Are you going to Pittsburgh? Did you know anyone in Pittsburgh?” Then I looked at my news app and saw that there had been a shooting at a synagogue in Squirrel Hill. It immediately registered as the neighborhood where my father and grandfather and great-grandfather had all lived.

My father was a fifth-generation Pittsburgher and his family settled in Squirrel Hill pretty much around the time that Jews were settling there around World War I. I felt afraid for the community. I felt a connection to the community.

To be clear, I grew up in Springfield, Massachusetts, but I knew, as a historian of American religion, that Squirrel Hill has a special place in the annals of American-Jewish history as an extremely old, extremely stable Jewish community, having been substantively Jewish for about 100 years. The irony that this terrible attack would happen to this community that has been so special to American Jewry felt like it called out to be explored more. I also got curious about how a community that has so many advantages in terms of stability, in terms of having multigenerational families, in terms of walkability, good urban street life, local institutions, schools, synagogues, churches, shopping districts, how it would be resilient in the face of something terrible.

What does the community represent to you, and did that change because of the shooting?

My father had this wonderful idyllic childhood in a community where it was safe, where people looked out for each other, where there were Jews of all kinds, ranging from the most secular to the most Orthodox, and that people basically lived pretty happily. I also knew that Pittsburgh was a good city in which to be Jewish, that antisemitism is fairly low, that it’s a city of ethnic neighborhoods and that people respect the different ethnicities. I knew it as a special place. I don’t think the shooting changed what it meant for me at all. I feel bad for Pittsburghers that now some people will think of an act of violence when they think of Pittsburgh, but the city itself and its neighborhoods are as wonderful as ever. I don’t think that the shooter changed that.

For whom did you write the book?

I always write for the public. I always write with the hope that anyone who’s curious about human beings and anyone who wants to read something interesting will find that in my work. I think the book will be interesting to Jews, but it’s not at all meant only for Jews. I think it’s meant for everyone who is curious about the human experience and about the way people cope with difficult times. With that said, the book isn’t strictly a Jewish book, nor is it strictly a Squirrel Hill or Pittsburgh book. It seems to encapsulate everybody and everything.

Given that you don’t live in the neighborhood, why did you think you were the right person to write this book?

I think there are a lot of right people to write about everything. There should be multiple books about every aspect of human experience. My book is the third book that touches substantively on this shooting. I’m not a Pittsburgher, I’m a journalist. Journalists should go everywhere that their curiosities take them, and they should report what they find as truthfully and as empathetically as they can.

You named the shooter in the book. Many in the local media, including the Chronicle, will not do that. Why did you make that decision?

As somebody writing for posterity, I have no choice. Imagine if all the books about the Tree of Life shooting didn’t name the shooter. How would anyone study the shooting, how would we have an accurate record of this hateful, antisemitic, bigoted terrorist act? We need the names of historical Nazis, of historical racists, of historical antisemites, of historical terrorists. These are crucial to the public record. I did not feel that I had a choice.

One of the points you make is that there’s a cottage industry built around each mass shooting, but aren’t books like this part of that industry?

That’s a great question. It’s hard to think of my book and the two others that have come out of the past three years as representing an industry. It is certainly true that journalists who cover sad events have to deal with the irony that they’re making their livelihood writing about sad events. There’s no way around it. Journalism about sad events and about destructive human behavior should happen. It should be a profession that’s done by people who do their best to be ethical and competent. You wouldn’t want it done only by volunteers or only by people who lived through it. We are often paid to investigate other people’s misfortune. And that doesn’t always feel great. But I do think it’s important work, especially in a free society.

What are the lessons that you’ve learned from writing the book?

Squirrel Hill reminded me of something that other reporting had led me to believe: Most people flourish more and thrive better when they live in relatively dense, walkable close-knit neighborhoods. For most people, that’s a better way to live. And that if bad things happen to them, they will be grateful for the proximity of their friends and neighbors.

This interview was originally published in the Pittsburgh Jewish Chronicle. Click here to get the Pittsburgh Jewish Chronicle’s free email newsletter delivered to your inbox.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.