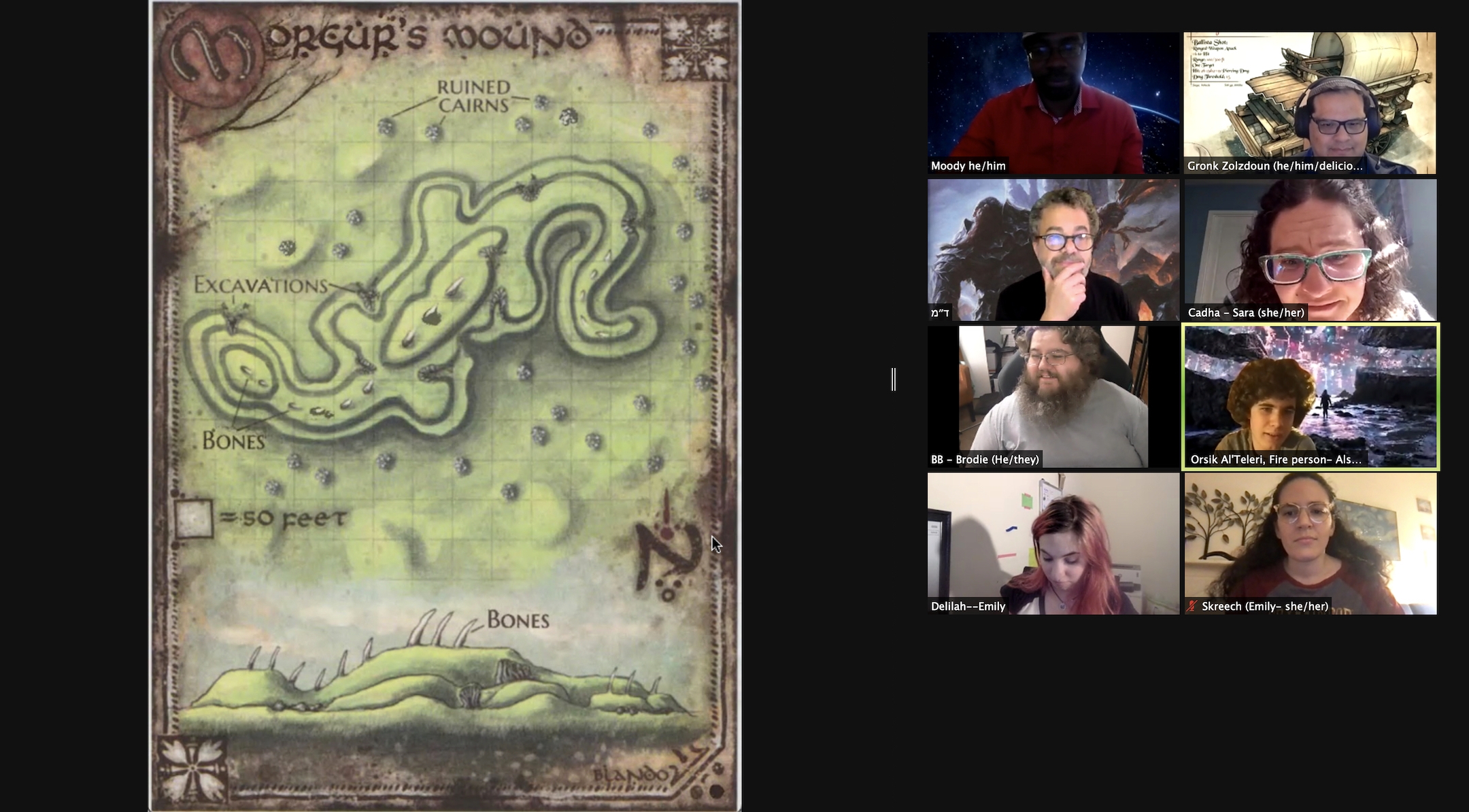

(JTA) — The adventurers arrived at Morgur’s Mound, an archaeological site ringed with dragon bones. There they stumbled upon some treasure: a fire giant’s gold-plated tooth. They grabbed the tooth and tried to leave the site, but suddenly the ground began to shake.

“Four animated thunder beast skeletons erupt from the mound and attack you,” the dungeon master said. “You desecrated a holy site, and these are the guardians of the holy site. Everybody roll initiative.”

“Are you allowed to roll on Shabbos?” a player wondered, breaking the fourth wall of the game.

“You’re allowed to roll on Shabbos,” another answered, “but you’re not allowed to pick up a pencil and write down your hit points.”

So began a recent session of Dungeons & Dragons, the classic fantasy role-playing game once associated with hardcore geek culture that has been more widely embraced in recent years.

As evidenced by the banter, this is a special group of D&D players. They’re all rabbis, but for one rabbinical student and one rabbi’s son, and live around the country. They are “a cross-section of American Judaism,” as one put it, representing the major denominations, from Reconstructionist to Orthodox.

“We did not intend to be a demonstration of Jewish pluralism,” Emily Dana, a third-year rabbinical student at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in Cincinnati, wrote to the Jewish Telegraph Agency in an email. “We just wanted to kill some giants.” Yet their sessions have shown her “it is possible to have people from incredibly different backgrounds be able to converse and debate in a friendly way with each other.”

Many of the group members identify as queer, Jews of color (or both) or disabled. Most have never met in person. But since August 2020, when the idea to form an all-rabbis D&D group began circulating on Twitter, the eight of them have spent many Sunday evenings together on Zoom trudging across mythical lands and fighting goblins, occasionally live-tweeting their campaigns — all while bonding over their shared love of Judaism and D&D.

For them, the sessions are more than just escapism. They are opportunities to open up about difficulties they have experienced in their field and hold meaningful dialogue about issues of identity and inclusivity, both inside and outside the Jewish world. They’ve also used the space to provide emotional support to each other through the pandemic, mentor younger group members and incubate personal projects. And when one rabbi left his pulpit after he was found to have sexually harassed his cantor, their sessions became a space for teshuvah, too.

“Rabbis are nerds,” Rabbi Erik Uriarte said when asked why a group of rabbis would want to play D&D together. “You kind of have to be if you want to do this job, so there is a lot of overlap with sci-fi, fantasy and gaming.”

A lifelong D&Der who plays a half-orc bard named Gronk Zolzdoun, Uriarte recently moved to New York to take a position at Temple Israel in suburban Lawrence after several years as a student rabbi in Billings, Montana. Board game meetups in Billings had been “a big social outlet” for him, so when COVID closed off the opportunity to attend them, he was excited to join the D&D group.

For Rabbi Sara Zober, playing D&D with her fellow rabbis has helped sustain her through the pandemic. In addition to leading Temple Sinai in Reno, Nevada, with her rabbi husband, Zober has four young children. She said she eagerly anticipates the game sessions, when she can shed her public persona and lose herself for a few hours in her character, a dwarven barbarian named Cadha Stoneshield.

“We all look for places where we’re not the rabbi, or where we’re not ‘Rabbi’ as our first name, and finding those spaces has been even harder since the pandemic because many of us are isolated,” Zober said. “This lets me be the ragey, shoot-em-up action figure that I wish I could be sometimes.” She added that she appreciates the relaxed atmosphere, where “if I drop an F-bomb, we’re not going to have a board meeting about it.”

Rabbi Sara Zober, who leads Temple Sinai in Reno, Nevada, is a regular at the all-rabbi Dungeons & Dragons Zoom games. She plays a dwarven barbarian named Cadha Stoneshield. (Courtesy of Zober)

Zober has been playing D&D since age 14, having learned the rules from her uncle. Historically, she said the role-playing world has not been overly welcoming to women, while the Jewish world has not always been inclusive of multiracial Jews. The rabbis D&D group is special because it breaks both molds.

“We all bring our full selves to the table, and what that means is I get to deal with the fact that I’m Hispanic and queer and a Jew by choice,” she said. “When we talk about [our identities], everyone in the room is on the same page. And we can laugh about stuff that in other spaces wouldn’t be funny.”

Indeed, joking is a big part of the game sessions, and no topic is out of bounds in such a diverse group.

“We can joke about the differences between the various streams of Judaism, and the different experiences between white Jews and Jews of color,” said Uriarte, whose father immigrated to the U.S. from Nicaragua. “It’s a way to get a whole lot of different perspectives on things.”

To Rabbi Shais Rishon, a prominent Black Orthodox rabbi and writer in New City, New York, the group represents a place where everyone can be their unfiltered, imperfect selves.

“This is a space where it‘s like, hey, there are things that we don’t know, and it’s OK to say that in this space without it being seen as a knock on our scholarship, or our knowledge base, or our authenticity,” he said.

It is also the place where Rishon first raised the idea of writing a new, anti-racist Torah commentary, which his colleagues encouraged him to do.

The first edition of D&D was published in 1974, and while it is now in its fifth edition, Uriarte said there are still elements that some players find dated and problematic. For example, he and his fellow rabbis wrestled with why particular “races” of characters like goblins and orcs are considered evil, while other races like dwarves and gnomes are considered good. They decided to ditch the standard races in favor of more complex character identities.

“We’re deconstructing and decolonizing certain tropes that have been harmful,” Uriarte explained.

This commitment to social justice faced an early test when Rabbi Jonathan Freirich, the group’s dungeon master (a D&D term for the game’s narrator), left his real-life congregation following a sexual harassment investigation.

In fall 2020, only a few months after the D&D group’s formation, The Buffalo News reported that the Central Conference of American Rabbis, the Reform movement’s leadership body, had censured Freirich for five ethics violations he committed while serving as rabbi at Temple Beth Zion in Buffalo.

According to CCAR’s confidential fact-finding report obtained by The Buffalo News, Freirich’s violations included making “inappropriate comments” about and around his synagogue’s then-cantor, Penny Myers, who had lodged a formal complaint with the CCAR in 2019 accusing Freirich of creating a hostile work environment. Freirich left the congregation in December, and Myers subsequently resigned after 14 years at TBZ, citing the way synagogue leadership handled the conflict.

Asked to comment on the situation, Freirich told JTA, “I said some things I regret, and I have been trying to be a more respectful and more caring person.”

As his censure became public, Freirich was still getting to know most of the other members of the D&D group. (His 13-year-old son, Jude, is also a member.) He said he shared what was happening with them, and nobody left or expressed qualms about playing with him.

“This is a supportive group of friends and colleagues,” he said, his voice full of emotion.

The two other Reform rabbis in the group, Zober and Uriarte, told JTA that they believe Freirich is committed to making amends.

“Jonathan is going through the teshuvah process that the CCAR has set out for him, and I have every faith that he will complete that process,” Zober said. “As a woman who considers myself a colleague to both Rabbi Freirich and Cantor Myers, I believe in the power of the teshuvah process and hope that all parties are able to heal and rejoin the Jewish community.”

Uriarte shared similar thoughts, saying that he believes Freirich is “sincere about hearing things that are uncomfortable and doing things in the pursuit of teshuvah.”

In an interview, Myers told JTA, “If there was really a teshuvah process, I would think that I would know about it, or that he would have made an overture to me. That has not happened.”

Other group members include Rabbi Emily Cohen, spiritual leader of the West End Synagogue in Manhattan, and Rabbi Herschel “Brodie” Aberson, who leads Temple Beth Sholom of the East Valley in Tempe, Arizona. A Reconstructionist rabbi and a self-identified queer millennial, Cohen said her half-rogue character, Skreech, “has a little bit of me in it, being off the beaten track slightly from what people might expect.”

Cohen is a D&D newbie, while Aberson is a veteran who estimated that he plays at least 12 hours of the game a week with different groups. Aberson said he hopes to pass on his passion for D&D to the young members of his Conservative congregation.

“Once this pandemic thing is a little bit less problematic, I have dice sets and dice trays to give to kids to run a game for them at my synagogue,” he said.

For now, the rabbis say they will continue to play on Zoom as their schedules permit. There is a waiting list of those who want to join their sessions, Freirich said, but “the group is as big as it can get right now.”

Back at Morgur’s Mound, the adventurers fought off the thunder beast skeletons with surprising efficiency with the help of some lucky dice rolls. Dana rolled a “nat 20” (the maximum value on a 20-sided die) and a 92 on her percentile roll, allowing her character — a half-elf paladin, or holy warrior, named Delilah — to smite one of the beasts with a longsword at close range.

“I am waiting for the day when we [rabbis] get ‘divine smite,’” said Zober, referring to one of the paladin’s magical powers.

“We know why we don’t have ‘divine smite’ — we wouldn’t have anybody in our congregations!” Rishon joked.

“Fair point,” Zober replied.

“So you have your relic, and you survived the thunder beasts’ assault,” the exiled dungeon master told the group. “What are you guys going to do now?”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.