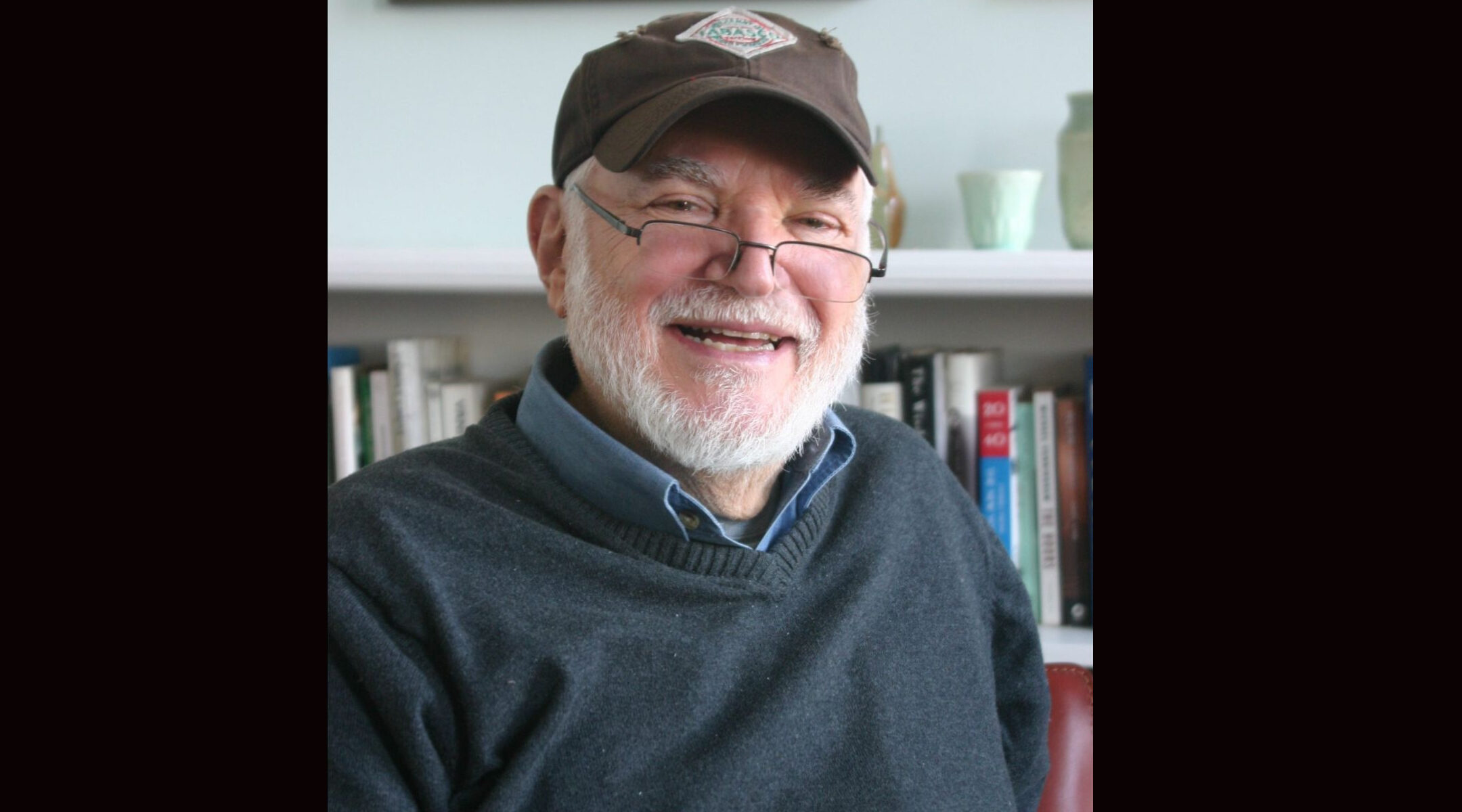

(JTA) — Nach Waxman, owner of the beloved New York City cookbook store Kitchen Arts & Letters, as well as a maven of both Jewish cooking and Jewish texts, has died. He was 84.

Although Waxman had struggled with his health in later years, his death on Wednesday was sudden, according to an announcement by his Upper East Side shop.

“He built the store into a worldwide haven for people who were serious about food and drink books,” the announcement read. “He encouraged the best authors, respected the passion and curiosity of cooks and readers at all levels, and never lost a sense of pleasure and wonder at discovering the myriad ways people wrote about cooking, eating, and drinking. All of us who worked with him will miss him deeply.”

Waxman was a mainstay of a small group of friends who met every Sunday morning for more than 25 years at his Upper West Side apartment to study Jewish texts.

As much as he loved studying Torah, Waxman was equally devoted to traditional Jewish foods, especially schmaltz and liver, and kept a collection of his own Jewish cookbooks in the back of his store.

Joan Nathan, the Jewish food writer and author of multiple Jewish cookbooks, said Waxman helped her find Yemenite and Sephardic cookbooks — often synagogue and community cookbooks from all over the United States — before those styles of cooking became popular among Ashkenazi cooks.

“We clicked right away, and clicked over brisket because he really liked brisket,” said Nathan, who first became friends with Waxman in the 1980s.

Waxman grew up in Vineland, New Jersey, a town that was once home to a community of Jewish farmers. According to a 2011 profile in the Forward, Waxman’s father sold real estate insurance to Jewish poultry farmers in the area.

Waxman attended a Jewish day school in Philadelphia, which meant traveling by train early each morning and returning home late in the evening. But the long commute did not prevent him from falling in love with Judaism.

He set out after college on the academic track, studying for a doctorate in anthropology but moving into the publishing industry and working as an editor. His love of literature extended to the Bible.

Rita Falbel, a friend and member of the Sunday morning study group, said Waxman brought an editor’s eye to the text and a food enthusiast’s hunger for knowledge.

“Interested in everything, wanting to know about everything, he was that kind of person,” Falbel said. “He would never let anything go until he figured it out.”

The group originally began with a few parents who met at the Stephen Wise Temple while their children attended Hebrew school. The meetings eventually moved to the Waxmans’ apartment, where the group would usually nosh on bagels and lox while they studied. On holidays, however, Waxman would prepare a special breakfast like latkes for Hanukkah and matzah brei for Passover.

“He was a wonderful cook,” Falbel said, before correcting herself and adding, “Chef, actually.”

“They have a total love of study, they had a great intellectual curiosity and a sense of wow isn’t that amazing,” said Rabbi Jeremy Kalmanofsky of Congregation Ansche Chesed, where Waxman and his wife, Maron, were members.

Kalmanofsky said the Waxmans arrived exactly on time for services each Saturday morning and stayed through the end. Waxman’s son, Joshua, is a Reconstructionist rabbi in New Jersey and has taught at the same school his father attended as a child. The Waxmans also have a daughter, Sarah, and several grandchildren, about whom Waxman frequently boasted about at the study group and at synagogue.

Leah Koenig, a food writer and author of several Jewish cookbooks, met Waxman when she found his recipe for russel, a fermented beet broth made by Russian Jews to add to borscht, in an Anshe Chesed community cookbook. She visited Waxman at his home in 2019 to learn how he made the broth in his mother’s old ceramic crock used exclusively for that purpose each spring in preparation for Passover.

“Growing up, we kept the crock in a special cabinet in our cellar where the Passover dishes were stored,” Waxman told Koenig. “It was something you waited for. There was real excitement when the crock came out and the beets were done.”

Waxman described russel in the Anshe Chesed cookbook as the dish that “heralded, as clearly as a shofar blast, that change was on the way —that we were beginning the countdown to Pesach,” according to Koenig.

“I think he’s somebody who understood the importance of cookbooks as literature and understood the importance of food books to telling cultural stories,” Koenig told JTA.

But the Jewish recipe Waxman will be best known for is his brisket. The onion-heavy recipe — developed as a hybrid of his mother and mother-in-law’s techniques — was first published in the 1989 “New Basics Cookbook.”

Nathan said Waxman’s work was a labor of love.

“There’s nobody like Nach — in a way it’s just a different time now. People are more entrepreneurs. He did this for the love of it,” she said.

On Sunday, Waxman’s study group will not meet during the shiva period. Falbel said she didn’t know when the group would get together next, but she knew Waxman and his enthusiasm — for food, cooking, literature, culture and Torah — would be sorely missed.

“He always had something to say, as most of us did, but he would say it with such enthusiasm,” she said.

Struggling to fully describe her friend, Falbel asked: “How can I describe somebody who loved life in all its forms?”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.