(JTA) — When an auction house recently unveiled a new catalog of rare Jewish books and manuscripts, Rabbi Elli Fischer was among the many who rushed to examine the goods.

An Israeli-American university researcher, Fischer was particularly intrigued by an old handwritten journal — opening bid: $100,000.

The journal, known as a ledger, or “pinkas,” belonged to a rabbi from the holy city of Tiberias who had toured Jewish Europe some 200 years ago to raise money for his community. Fischer was fascinated to read the names of towns and rabbis visited on the tour. He even spotted the signature of one of his own ancestors, a German rabbi.

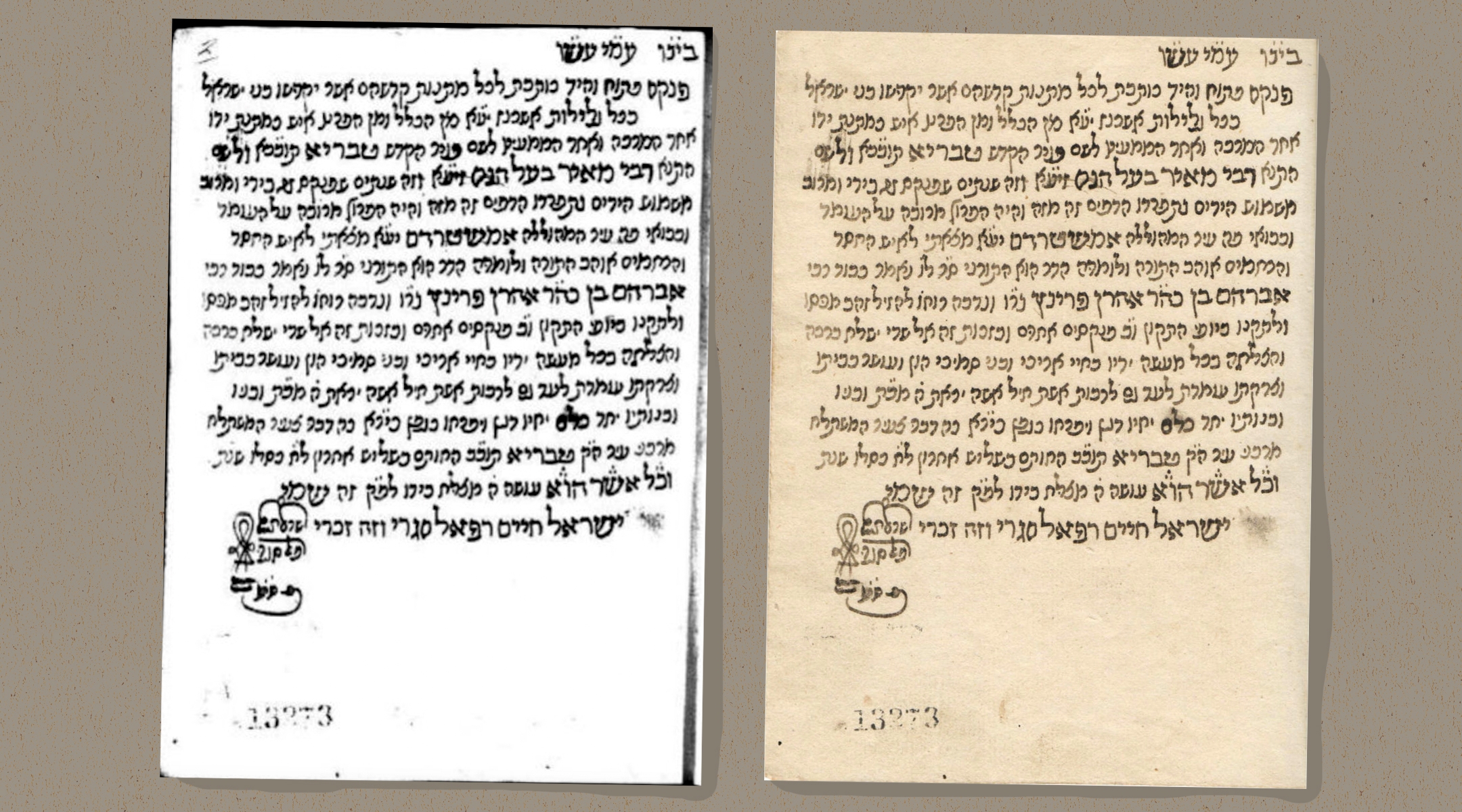

As Fischer looked through the digitized images of the ledger, he noticed a number stamped at the bottom of one page. The stamp, showing a faded “13723,” told Fischer that this manuscript, now being sold by an anonymous owner on the private market, had once been part of a collection, probably at a public institution.

“There’s something really curious, perhaps even suspicious, about one of the most remarkable items on auction,” Fischer would later write in a series of tweets.

Fischer turned on his detective’s brain, and what he would discover would soon scandalize the world of Judaica experts, help expose a controversial practice by a flagship institution of Jewish learning and raise questions about the commitment of the Jewish community to preserving its own history.

All he had now, however, was a serial number. Fischer decided to type the number into the search bar of the catalog for the National Library of Israel — he got a hit. A description matching that of the auction noted that the manuscript was available in microfilm and digital formats on the library website.

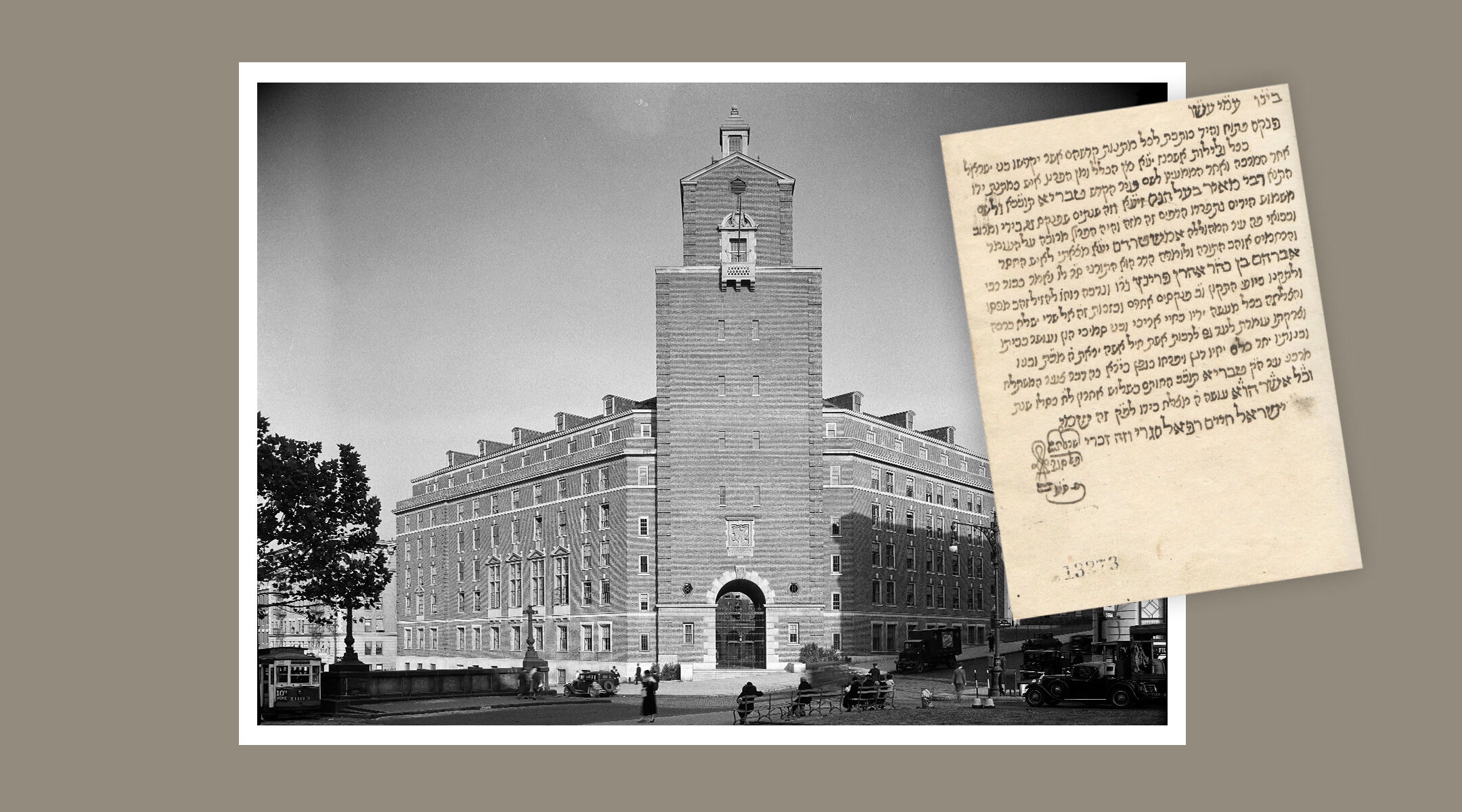

But the item did not belong to the National Library, nor had it ever. Instead, the manuscript was described as part of the world-renowned collection of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America in New York.

“You read this right: A unique and valuable manuscript that was part of the [JTS library’s] magnificent collection is now on the auction block,” Fischer would later tweet. “How did it get there?”

The manuscript page on the right, with a serial number stamped near the bottom, was featured in the online catalog of the Genazym auction house. It matches the manuscript page on the left found in the collection of digitized manuscripts maintained by the National Library of Israel. (Genazym and Jewish Theological Seminary)

Fischer also noted that a search for the item in the library’s own catalog yielded no results, only another question: Had someone removed the entry from the catalog?

One possibility was that the manuscript had been stolen from the seminary at some point and was now resurfacing. The other possibility —even more worrying to some — was that the seminary was quietly selling the manuscript and perhaps other precious items from its celebrated collection.

The library had sold off items in the past, doing so openly. The items were either duplicates and therefore less valuable, or works printed in Latin, a language that many other institutions better specialize in.

This manuscript was a distinctly Jewish and Hebrew text, and since it was handwritten, by definition it was unique.

As word of Fischer’s findings spread, librarians at JTS and elsewhere grew alarmed, according to interviews with about a dozen people, all of whom spoke on condition of anonymity.

With the library shut down since 2016 for a campus redevelopment project and the books sitting in a warehouse, rumors had been circulating. Many suspected the library used the cover of renovations to make the controversial move of selling collectibles.

Fischer had delivered a “smoking gun,” as several Jewish book experts described his discovery that an item had been removed from the library. One person called it a “catastrophe.” Another expert said the sale of the manuscript was as if Hadassah had removed the Chagall windows from its hospital in Jerusalem. The subsequent removal from the catalog was as if Hadassah had been asked about the windows and responded, “Windows? What windows?”

Rabbi Elli Fischer’s discovery helped expose a controversial practice by a flagship institution of Jewish learning. (Kinneret Rifkind)

Located in Upper Manhattan near Columbia University, the Jewish Theological Seminary is the academic and spiritual heart of Conservative Judaism. Its library is arguably the most important repository of Jewish knowledge in the world, featuring some of the very first books printed in Hebrew, a letter written by Maimonides about 800 years ago, and thousands of other rare and unique texts.

A tension between the institution’s mission of ordaining rabbis for Conservative congregations and its expensive archival responsibilities have existed for more than a hundred years, going back to the moment when rich New York Jews envisioned a ”Hebrew book museum” at the seminary to rival the collections of imperial Britain.

“We should hold in view the purpose to make our collection as nearly complete as the resources of the world may render possible, and in so doing, we should spare neither thought nor labor nor money,” said Mayer Sulzberger at the dedication of a new building for the seminary in 1903.

Sulzberger and the rest of the era’s mostly German Jewish donor class made good on that promise. Alexander Marx was tapped to head the library in 1903, and he embarked on a buying spree that lasted for decades.

“Marx was the bibliographical equivalent of a kid in a candy shop,” said David Selis, a historian studying the library. “He would buy anything that has any relationship to Jews in any language.”

But as it turned out, money for a museum of the Hebrew book did not remain as readily available in the 21st century.

In 2015, the seminary signed real estate deals that saw the library building demolished and replaced with a luxury residential tower. The proceeds, some $96 million, boosted the institution’s endowment and paid for a campus redevelopment project featuring a new library with a much smaller footprint, as well as a new dorm and auditorium.

After having been closed for construction for years, the library is set to reopen in the coming months, COVID permitting, with only a fraction of the books available on site. The rest can be called up from a distant warehouse.

In the world of Jewish books, the real estate deal was widely understood as a divestment by JTS from book custodianship in favor of its mandate to train rabbis. But most have refrained from saying so publicly, according to interviews, because they do not want to be seen as disparaging or undermining an institution that remains essential for serious scholarship about Judaism.

While the seminary was tapping its real estate for cash, it also decided to cultivate another revenue stream.

As many had suspected, and seminary officials confirmed to JTA, the library had quietly sold off rare items from its library.

The ledger of the rabbi from Tiberias went to a private collector in 2017 and eventually wound up on the auction block, served up by a Jerusalem-based firm called Genazym. The auction takes place on Wednesday.

“The sale of this piece was deemed to be of minimum impact to the collection and financially prudent for the institution,” JTS spokesperson Beth Mayerowitz said in an email to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency providing the first public confirmation of such a sale.

In an interview, the seminary’s chief librarian, David Kraemer, described the instructions he had received from his superiors: The administration and the board of the seminary wanted him to sell items of his choosing in order to raise a specified amount of money. Kraemer did not disclose the dollar figure.

“I asked, ‘What in my collection would raise that amount without harming the core mission of the institution?’” Kraemer said, recalling a conversation with a few in-house experts whom he declined to name. “It had to be an item we had digitized and that we deemed relatively low research value.”

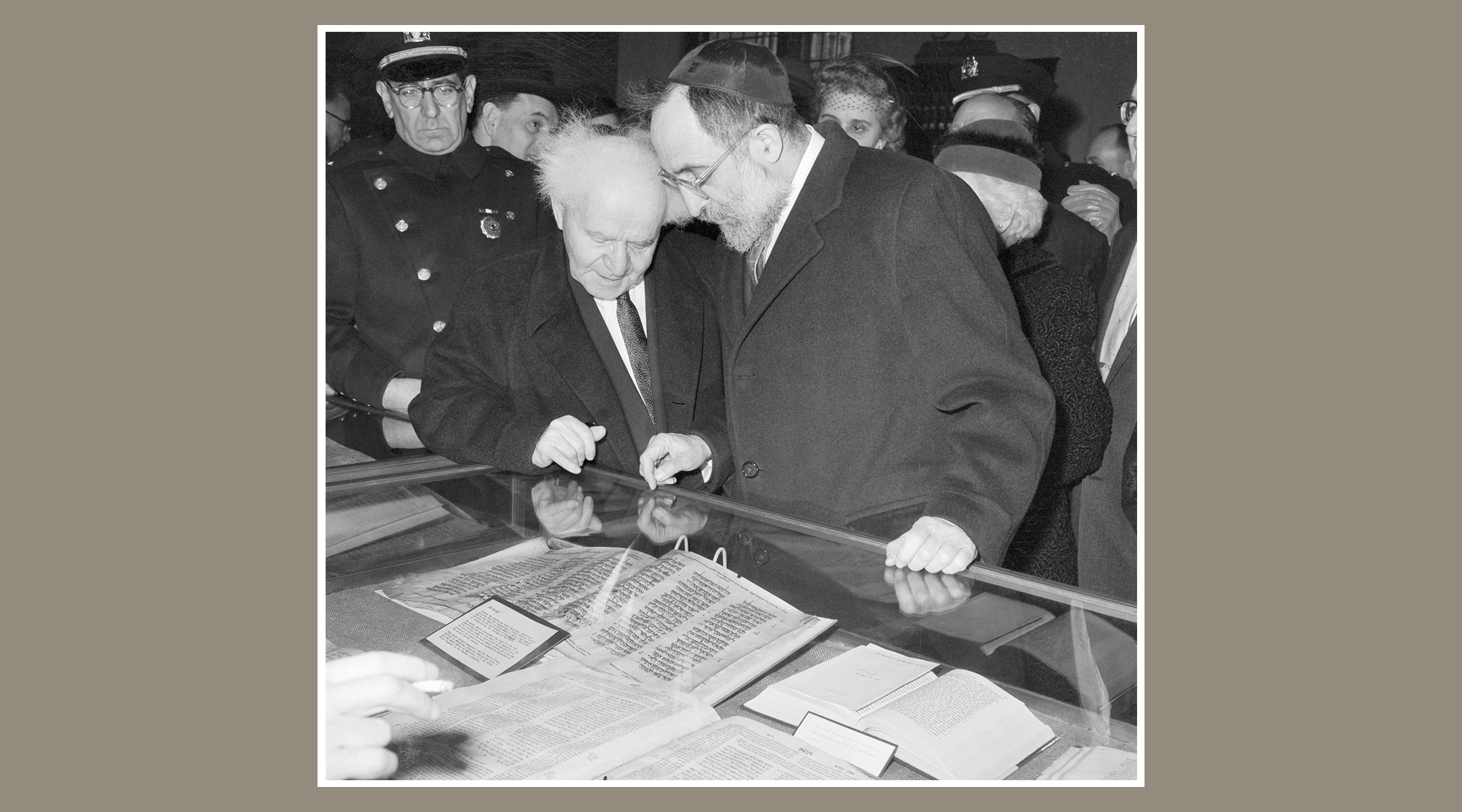

Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, left, of Israel views rare books and scriptures under glass in a case at the library in the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, 1960. (Getty Images)

The task facing Kraemer was not as unusual as it might seem. Libraries and museums periodically sell items, a practice known as deaccessioning, often to raise money for the purchase of other items but sometimes under financial duress.

Because the library at JTS was founded on almost indiscriminate buying, it had come to possess multiple copies of many books, even remarkably rare ones published at the dawn of printing.

In fact, the library had once held an extra copy of the first printed Hebrew book to be illustrated, Meshal ha-Kadmoni, or Fable of the Ancients, by Isaac ben Solomon Abi Sahula, printed in 1491 in Italy.

In 1986, the book was sold as part of an auction through Christie’s, fetching the highest price ever paid for a printed book in Hebrew at the time. The library sold 95 items in that round and raised a total of $700,000.

In the decades since, the library has gained a reputation for sometimes undervaluing its possessions. In 1998, for example, a copy of the first printed edition of the Torah in Hebrew that the library deaccessioned in a $50,000 deal quickly went on to sell for $310,000 at an auction.

By 2015, when JTS was reportedly amid a financial crisis going back years, the seminary again mined its library and set up an auction, this time through Sotheby’s. But now the library wasn’t offloading duplicates.

JTS put up a series of works in Latin that are so old that they are not called books but incunabula, a designation for items printed before 1501. The sale included a 1455 edition of the Book of Esther from a Gutenberg Bible — it had been among the items showcased for donors on private tours of the library. The eight pages, “handsomely rubricated in red and blue,” sold for nearly $1 million, far beating expectations.

Kraemer explained that books in Latin are outside of the library’s “core mission” and scholars rarely come asking for them. The money collected went to a fund to buy more relevant rare books, he added.

An academic library like that of JTS has the legal right to sell anything it owns for any reason without publicizing it. In practice, libraries turn to deaccession only when they are facing budget shortfalls or have an opportunity to trade up, and they tend to publicly announce they are doing so. There are different views on what’s appropriate, but even those who frown upon particular deaccession decisions can accept the overall practice.

It was the lack of transparency around the sale of the manuscript that especially riled Judaica librarians and consultants, many of whom wondered what other items might have slipped away unnoticed.

Indeed, other such private sales have taken place in recent years, according to seminary officials.

“The sale of Pinkas Shadar of Israel Hayyim Raphael Segre (1807-1809) and several other items took place in a private sale in 2017 and was one of a few sales that occurred since 2015,” Mayerowitz said.

Among the items that went, she added, were several volumes of the Bomberg Talmud printed on blue paper and a copy of the Prague Haggadah on parchment.

“Those of us who are book people in our blood, we see this and we get pissed off,” a former library employee said. “These books don’t belong in a private collection. If JTS had been transparent I could almost understand. But they are selling books out the back door. The seminary is using the library as a cash cow.”

Kraemer rejects the idea that the sale and subsequent removal from the online catalog were inappropriate.

“The sale wasn’t announced because it was a private transaction,” he said. “People will interpret it how they will interpret it.”

Part of the reason why it’s hard to evaluate whether the seminary acted properly is that it doesn’t have a set policy on deaccession. The library at nearby Columbia University has a blanket policy against it, as does Yeshiva University, another Jewish institution of higher learning with a substantial albeit lesser Judaica collection.

Absent laws and mutually agreed-upon rules, each institution sets its own policy. That’s different from the related field of museums. The powerful Association of Art Museum Directors lists guidelines against deaccession, which were temporarily relaxed at the start of the coronavirus pandemic because of an anticipated budgetary shortfall.

Some librarians would like to see a change in their field.

“There aren’t norms and guidelines around deaccession, and that’s a problem,” said Michelle Margolis, the incoming president of the Association for Jewish Libraries.

Margolis, a librarian at Columbia, said she’s part of a group that’s working on a solution. Common ethics would make it easier to tell apart bad actors and suss out theft.

For all their desire to obtain what’s in the public domain, thieves, as much as private collectors, need institutions to exist and thrive. By warehousing precious books, libraries create scarcity on the market, allowing the few items that do circulate to fetch high prices.

Kraemer said he knows of no plans to sell more rare books, and the seminary says it is financially healthy. Like many institutions dependent on donations, the seminary was making emergency cuts at the start of the pandemic. But 2020 turned out to be one of its best years for fundraising in the past decade, according to Mayerowitz, the JTS spokesperson.

A strong fundraising year would appear to come on the heels of years of consistent growth for the seminary’s endowment. Tax audits disclosed through the IRS show an increase every year for which data is available, going from $113 million in 2015 to $142 million in 2019.

Mayerowitz also said that the seminary’s strong position is evident in its redeveloped campus with a performance space, residence hall and library, which she called “an investment in the future of not only JTS, but the entire Jewish community.”

A reminder of the cost of that investment presents itself against a slice of sky above the seminary. Where stacks of books once took up space, there are now 33 floors of luxury apartments — the towering Vandewater building is one of the tallest Manhattan buildings north of Central Park.

The bulk of the library’s books will now forever be stored in a remote warehouse, with any item available for recall within one business day. That’s common practice for research libraries, Kraemer noted, adding that the most commonly requested books as well as the entire special collection — rare books and manuscripts — will be housed on campus.

He said the decision to downsize the real estate and sell certain items was about being prudent and not a retreat from the 120-year-old promise to make the library the best of its kind in the world.

“The library will never fail,” Kraemer said. “It’s so valuable that it will always find supporters. I am very optimistic about the future.”

Against the optimism projected by seminary leaders are two long-standing countertrends in American Jewish life.

Judaism’s Conservative denomination, which counts the seminary as one of its essential institutions, was the largest Jewish denomination in the 1950s and ‘60s. It is no longer and is shrinking still. In 1990, the percentage of American Jews affiliated with the Conservative movement was estimated at 38%. A study from earlier this year pegged the number at 17%.

Meanwhile, Jewish librarians and historians of Jewish libraries speak with reverence and affection of benefactors past. They name-drop library donors who died early in the last century, such as “Judge” Sulzberger, Jacob Schiff and Felix Warburg. Nostalgia abounds for an era when philanthropists — rich secular and liberal Jews — were committed to preserving Jewish cultural memory as a service to the Jewish people.

“There just isn’t money for Jewish culture like there used to be,” said Selis, the historian of Jewish libraries. “A generation has passed. The culture has shifted in American Judaism.”

That a rabbi’s 200-year-old travelogue could fetch $200,000 at auction suggests demand for Jewish artifacts has not exactly dissipated as much as shifted somewhat. The marketing materials for the manuscript, published by the Jerusalem auction house Genzaym, speak to the change.

A map of the journey of Israel Hayyim Raphael Segre in Europe in 1807-1809 (Getty Images)

After a nod to the ledger’s historical value — like documentation of the era’s communal fundraising system — the marketing message focuses on the “priceless and exceedingly rare collection of autographs” of great rabbis visited on the tour of Europe. These rabbis, who signed the ledger to certify their donations, are named, described and, in some cases, illustrated in the auction’s catalog.

With its signatures, the ledger belongs to a class of books that have seen demand skyrocket, according to bookseller Israel Mizrahi of Brooklyn.

“The market for books with provenance of important rabbinical figures, as well as anything signed or autographed by such figures, has exploded in recent years, with prices more than doubling every decade in the last few decades,” Mizrahi said.

The increased competition for such titles is being driven by “the growing upper class” of Orthodox Jews, who see them as an investment but also as something else.

“In the Orthodox Jewish world, many of the status-symbol purchases common in the secular world would be frowned upon, but items of religious significance are viewed in a positive light,” Mizrahi said. “There is widespread belief that owning something that was used or written by a righteous person will bring good will to its owner.”

It’s perhaps too early to tell what the rising influence of Orthodox collectors will mean for the ideal of public scholarship and communal memory in the digital era. Will more items disappear into the thicket of private vaults without notice, or will the archives persevere and somehow find new patrons?

If Orthodox Jewish researchers like Fischer have their way, the spirit of collective heritage will win.

“These are treasures of the Jewish people, not of individuals,” Fischer said. “It’s important people have access to them.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.