You do not want me to recommend your next beach read.

The best novel I’ve read in months is also the most excruciating. “Shuggie Bain,” which won its author, Douglas Stuart, the 2020 Man Booker prize, is about a Scottish boy being raised by an alcoholic single mother. Trapped in the Scottish version of the projects, preyed upon by indifferent neighbors and predatory men, the parent and child see their roles reversed. Shuggie is constantly trying to distract his mother from her worst impulses and, at times, to keep her alive.

It’s a litany of misery, but told in such a singular, powerful voice that I never stopped to demand that the author ease up a little, or give me an “uplifting” ending.

I am also engrossed in a recent novel by Edna O’Brien, “The Little Red Chairs,” which includes two shocking acts of violence and gets no happier from there. The story of displaced people and asylum-seekers in modern-day London, it takes place under the shadow of the genocidal civil war in the former Yugoslavia.

Some readers might not even bother; with limited time and infinite possibilities, why choose sadness or misery? I flatter myself by saying these dark tales make me more sensitive to the struggles of others. Or perhaps I am wallowing in someone else’s misery just to make me feel better about myself.

The novelist Dara Horn writes about – actually against – those who read for “uplift.” In a Tablet essay, she objects that “even educated readers who appreciate tragedy still secretly expect a ‘redemptive’ ending, an epiphany, a moment of grace.” This is truly obscene, she writes, when applied to fiction about the Holocaust, where the real-life number of “happy” or redemptive endings is vanishingly small.

Horn expands on this idea in her forthcoming book of essays, “People Love Dead Jews,” which is exactly as uplifting as its title. She suggests that our impulse to expect redemption or grace at the end of a story is actually an inheritance of Western – that is, Christian – culture, where literature fulfills a need for readers to consider our world coherent and to find meaning at the end of every story.

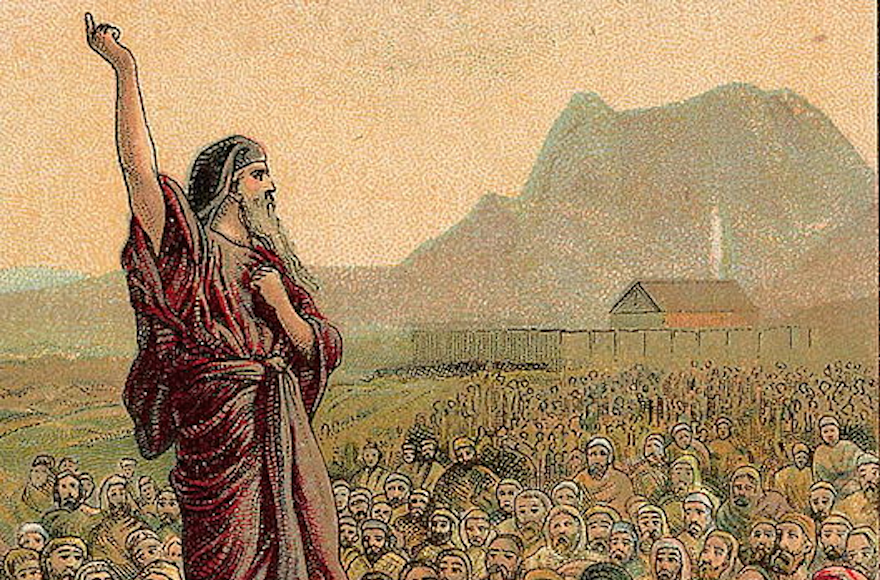

The Jewish literary tradition suggests exactly the opposite. The Five Books of Moses begins with a deeply flawed family and ends with the Jewish People on the brink of the Promised Land, their destiny unfulfilled. Moses, the hero, is denied his ultimate wish. In the Joseph novella, the hero lives to see his family reunited under his benevolent protection, but the victory is short-lived – the next thing we know there is a new Pharaoh and Joseph is quickly forgotten.

In the Torah portion Masei (Numbers 33:1-36:13), read this past Shabbat, the Jewish people’s long journey is about to reach a climax, and a war of conquest soon to get underway. But don’t cue the “Rocky” theme – the portion quickly swivels to discuss what to do when an unintentional murderer is committed and innocent blood is spilled. As Rabbi Avraham Fischer asks in a commentary on Masei, “Are there not more uplifting commandments to be dealt with than bloodshed?”

Fischer concludes that Torah hits a pause on the fanfare precisely because a triumphant “ending” might cause the people to desecrate the land at a moment when they are being commanded to conquer it in an “all-out, uncompromising war.” Because even “necessary and justified bloodshed can make a people callous towards the value of human life,” the Torah takes this moment to discuss the consequences of murder. It’s literally a cautionary tale.

Horn argues that this pattern of sometimes “grim reality” holds through the classics of Yiddish and Hebrew literature: novels with ambiguous endings or no endings at all. Or Holocaust novels that don’t require its dead Jews to “teach us about the beauty of the world and the wonders of the redemption.” I don’t mean to ruin “Fiddler on the Roof” for you, but Horn reminded me that in the original Sholom Aleichem stories, Golde and Motl the tailor both drop dead and Tevye’s daughter Shprintze drowns herself?

L’chaim!

So maybe my Jewish upbringing explains my tolerance for grim stories and unredemptive endings. Happy endings and moments of grace have their place, but I guess don’t trust them.

Happy endings and moments of grace have their place, but I guess don’t trust them.

But if the only stories we tell ourselves are downbeat and existential, perhaps we are betraying another Jewish tradition – one that seeks a sense of hope and possibility even after the very worst happens. Writes Horn: Jewish storytelling is about “human limitations,” which means a story is not the end but the “beginning of the search for meaning.”

Sara Bloomfield, who has the decidedly un-uplifting job of directing the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, says it this way: “Destruction can teach us why freedom, justice, and human dignity are important — and fragile. And, that when freedom and justice are denied and dignity is threatened, we still retain certain powers over our own humanity.”

I’ll leave it there. Not a happy ending, necessarily, but a meaningful one.

Andrew Silow-Carroll (@SilowCarroll) is the editor in chief of The Jewish Week. Subscribe to his Sunday newsletter here.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.