(JTA) — For Rabbi Michael Perice, the hardest thing about counseling congregants who have family members dealing with addiction had been holding back his own experience with substance abuse.

“I really wanted to let people know in these conversations that I understand. And I couldn’t do that,” Perice said.

Perice, the spiritual leader at Temple Sinai of Cinnaminson, New Jersey, decided to change that on Monday night by telling his congregation the story of his four-year struggle with opioid addiction. He celebrated 10 years of sobriety in April.

Perice knew that sharing his story would not be without its risks. A congregant could react poorly or lose respect for him after hearing about his struggle. But to Perice, breaking down the stigma associated with addiction and potentially inspiring someone to get help was worth the risk.

And perhaps most important, letting his congregation in on this part of his past is vital to how he views his role as a rabbi.

“In some ways, this is very personal and I can totally respect somebody’s feeling like, ‘this is my business, it doesn’t affect what I do.’ I feel about it differently,” Perice said.

“My congregants trust me. Who am I to not trust them? I feel like I’m honoring that trust by telling them something like this about myself, and I think that’s a very important part of this, honoring the trust people have put in me.”

Using to ‘feel normal’

Perice’s addiction began as many do: with a car accident, chronic back pain and a prescription for Vicodin.

The accident happened in 2007 when Perice was an undergraduate student at Temple University in Philadelphia and on track for a career in politics. While the Vicodin helped his back pain, he found himself needing higher and higher doses as his tolerance for the original dose increased.

When his doctor tried to get him to cut back, he began “doctor shopping,” seeking new physicians to prescribe more pain killers. Eventually he bypassed the doctors altogether to buy pills, until he was taking up to 80 milligrams of OxyContin each day.

Perice said the pills were never about getting high.

“I was dealing with depression and anxiety, like a lot of people in their early 20s, and I think for some reason, when I would take opiates for this pain, it would seem to just calm me down,” Perice said. After taking pills for a certain amount of time, he said, “you’re taking it to feel normal.”

As he started taking the larger doses, obtaining enough medication to feed his addiction became more challenging. One night in 2011, when his potential sources for pills turned up empty and the first symptoms of withdrawal started to hit, Perice grew desperate.

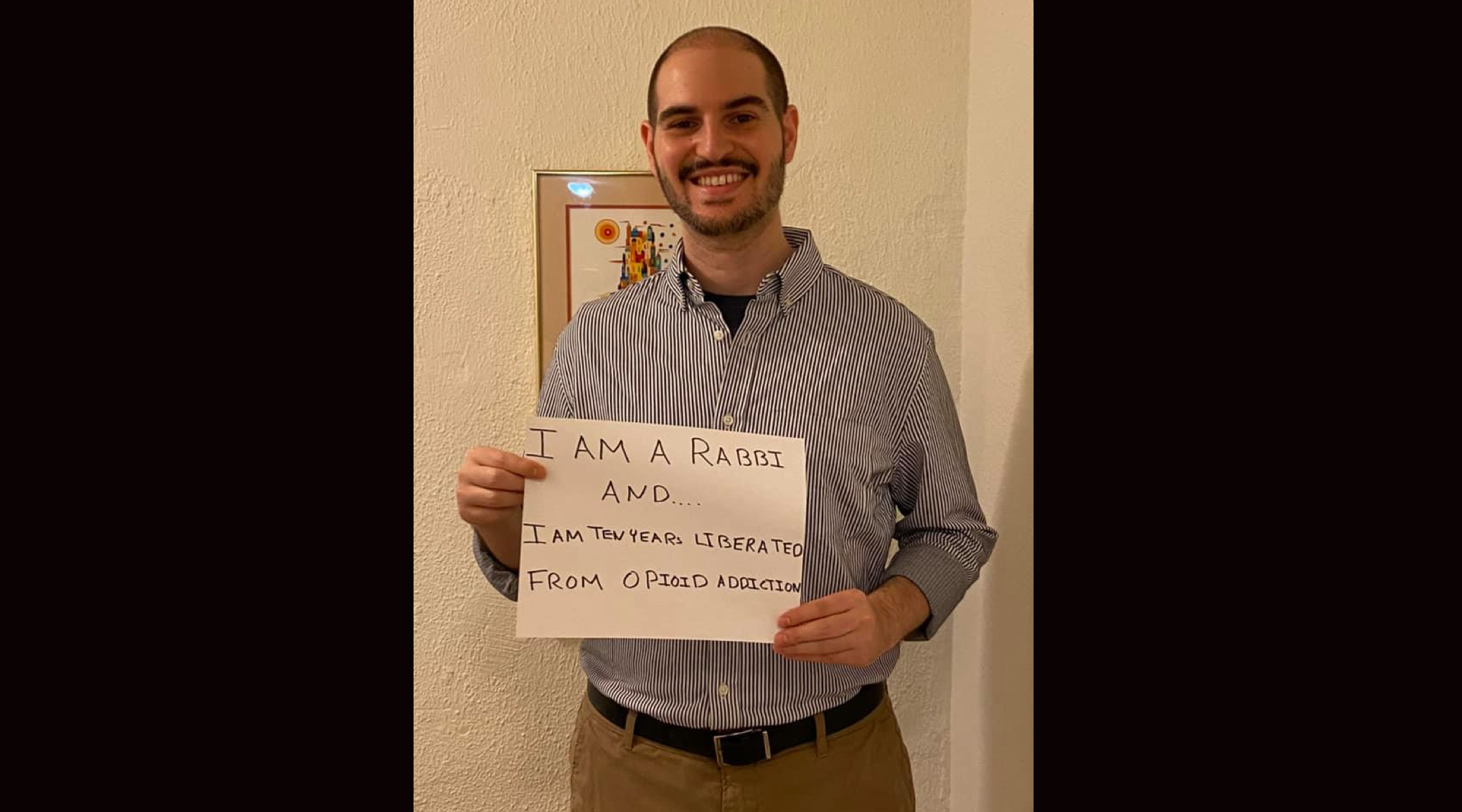

Perice said his phone didn’t stop buzzing with messages of support and love from congregants after sharing his story. (Courtesy of Perice)

He called a friend who was also using drugs at the time and asked him if he had any. When the friend arrived an hour later, he brought a bag of heroin, a drug Perice had never used.

Though he was not religious at the time, Perice described what happened next as something of a spiritual experience.

“I’m so conflicted on how to describe this feeling because I don’t want anybody to think that this is how it goes. But for me, it felt like a spiritual experience. It felt like a powerful experience where I was given an opportunity to make a choice, a choice I felt like I had never had over the past four years,” Perice said.

“Was that biochemistry? Was that God? Was that something else? I don’t know and honestly, it’s not important. What’s important is that I felt it and it felt very real to me.”

Whatever it was, Perice said he “felt a calm sensation come over me where I was able to really see myself for what I had become and what I would become if I went down this road. And in what was either the smartest decision in my life in retrospect, but felt like the dumbest decision at the time, I flushed [the heroin] down the toilet. And that’s when I called my parents.”

The next day, his parents set up an appointment with an addiction specialist. The doctor prescribed buprenorphine, a medication that mitigates the effects of withdrawal and can aid recovery.

Connecting to Judaism

During his recovery, Perice went to work at his family’s business, a Jewish funeral home in Philadelphia. Though he considered himself a secular Jew at the time, Perice started to become more interested in Judaism through his work at the funeral home and with its rabbis.

On a winter day when heavy snow blocked the path to the graves, Perice kept an elderly woman company as she watched her brother’s funeral from a car parked nearby.

As they sat in the car, Perice asked the woman if she wanted to tell him about her brother. The woman said yes and began recounting how she and her brother had survived the Holocaust. Perice asked if she wanted to say a prayer and the two recited the Mourner’s Kaddish together. Perice walked away from the encounter resolved to spend his life connecting with people the way he had with the woman.

“I remember walking out of the car being like, what did I just do? And how do I always do that?” he said.

Rabbinical school was not an obvious choice for Perice. Growing up in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, he had been a member of Congregation M’kor Shalom, whose rabbi, Fred Neulander, made national headlines when he was convicted and sent to prison for hiring two men to murder his wife.

The murder turned Perice, 11 years old at the time and already a self-described “rebellious Hebrew school student,” away from religion.

“I had my bar mitzvah at 13 and I was kind of done with it all,” he said.

But working at the funeral home allowed Perice to meet more rabbis and see the profession in a different light.

After spending a year studying in Israel to improve his Hebrew skills, Perice began studying at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College in 2014. He graduated and began working at Temple Sinai in 2020.

Perice said he had known since rabbinical school that eventually he wanted to share his story of recovery with his congregation. But he was advised by mentors, including LGBTQ colleagues who had gone through the process of coming out to their congregants, not to share his story immediately but to wait until he felt comfortable with the community.

Stigma and opportunity

Now that he’s been at Temple Sinai for a year, and having recently celebrated the 10-year anniversary of his recovery, Perice felt ready to share his story.

Even as he did, he was aware of the risks.

“There might be some people who are uncomfortable with this. But my hope is that they will continue to trust in the work with me and I can help them work through whatever uneasiness they could possibly have with this, because part of stopping a stigma is leaning into the discomfort of why do you feel this way,” he said Monday before sharing his story with congregants.

“I am not a different person from the day before you knew this to the day after. I’ve remained the same. I’m exactly the same person you knew a week ago.”

Rabbi Mark Borovitz, the founding rabbi of Beit T’shuvah, a Jewish residential treatment center and synagogue in Los Angeles, said speaking openly about a history of addiction can be treacherous. Jewish communities in particular, said Borovitz, attach their own unique stigma to addiction.

“Jews are constantly and consistently trying to project an aura of perfection because we’re afraid if we’re not perfect they’ll all come after us,” Borovitz said, referring to antisemites.

Harriet Rossetto, the founder of Beit T’shuvah and Borovitz’s wife, said it can be even more difficult for rabbis than laypeople to be open about addiction.

“You’re a rabbi, you’re supposed to be a perfect image of piety and propriety,” she said.

Rabbi Paul Steinberg, who leads Congregation Kol Shofar in the Bay Area and is the author of “Recovery, the 12 Steps, and Jewish Spirituality: Reclaiming Hope, Courage and Wholeness,” said a rabbi speaking openly about addiction could play a key role in reducing the stigma and shame associated with addiction. And while some could react negatively to Perice’s story, Steinberg said, it could also deepen his bond with his congregants.

“He has the opportunity to let them into his heart in a new kind of way, that his heart is more spacious than what they might once have thought,” Steinberg said.

Perice with his wife, Rachael. (Courtesy of Perice)

Johanna Schoss, president of Perice’s synagogue, said she supported Perice’s decision to share his story.

“I think it’s going to be a relief and a help to a lot of families,” Schoss said Monday.

In March, Perice and two other rabbis introduced a resolution to the Reconstructionist Rabbinical Assembly calling for the movement to do more to address the opiate crisis. Their recommendations ranged from increasing the movement’s advocacy work, to taking steps to lower the stigma around addiction, to developing resources to educate communities about addiction.

A majority of the assembly adopted the resolution just a few weeks before Perice celebrated his 10th anniversary of sobriety.

That vote, and the support he received from his fellow congregants, inspired him to talk to his congregants about his story. He did so on a Zoom call Monday evening attended by several dozen congregants, after which he said his phone didn’t stop buzzing with messages of support and love.

Perice’s wife, Rachael, worried about whether everyone would understand, but was relieved at the response.

“I felt pretty overwhelmed with the love that was coming in from the community,” she said Tuesday.

Following that positive response, Perice hopes his story will inspire others to get help and to help others.

“We have to let people know that there’s nothing wrong with [you], there’s nothing immoral, you’re not guilty of anything,” the rabbi said. “You’re stuck in a very bad situation and you need help to get out of it. We all do.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.