(New York Jewish Week via JTA) — In March 2005, I was on the verge of publishing an article that I knew would have a major impact. As the editor and publisher of The Jewish Week, I would be describing — for the first time — the true nature of the sexual misconduct that led one of the most prominent Reform rabbis in America to resign from his role as president of Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, the movement’s seminary.

Rabbi Sheldon Zimmerman had resigned from HUC in 2000 and been suspended for two years from the Central Conference of American Rabbis, the movement’s rabbinic organization. The group had said only that Zimmerman had engaged in unspecified ”personal relationships” that violated its ethical code, and many believed that he had a long-ago consensual affair with an adult woman in his congregation.

I found out that the allegations were far more significant. I had spoken to one of Zimmerman’s accusers, who told me that he had begun behaving inappropriately toward her when she was a teenage congregant. She told me that their intimate contact, which recent reports indicated included touching and kissing, began when she was 17 and was consummated when she was 20.

Some of those details were revealed recently in an investigation by Manhattan’s Central Synagogue — Zimmerman served there as senior rabbi from 1972 to 1985. On April 27, the synagogue revealed the damaging findings of an independent study it commissioned last fall, providing details of the behavior that the CCAR had described only vaguely.

Why didn’t I publish the story more than 15 years ago? I knew that I had important information — information that could protect others as Zimmerman regained influence in his movement. But I did not have the full permission of my source, whom the CCAR had determined was trustworthy.

The following story explains why the facts remained a secret for all these years.

Credible allegations

Last month, Central Synagogue sent a letter to its community containing the results of an investigation into the events that led to Zimmerman’s suspension 20 years earlier. The investigation was prompted by a woman’s disclosure after last Rosh Hashanah that Zimmerman, now 79, “initiated an inappropriate relationship with her while she was a young religious schoolteacher and congregant at Central” in the 1970s.

The investigators found credible the allegations by this former teacher, as well as those of one women who came forward in 2000 and a third in 2020, of “sexually predatory behavior by Rabbi Zimmerman in the 1970s and 1980s.”

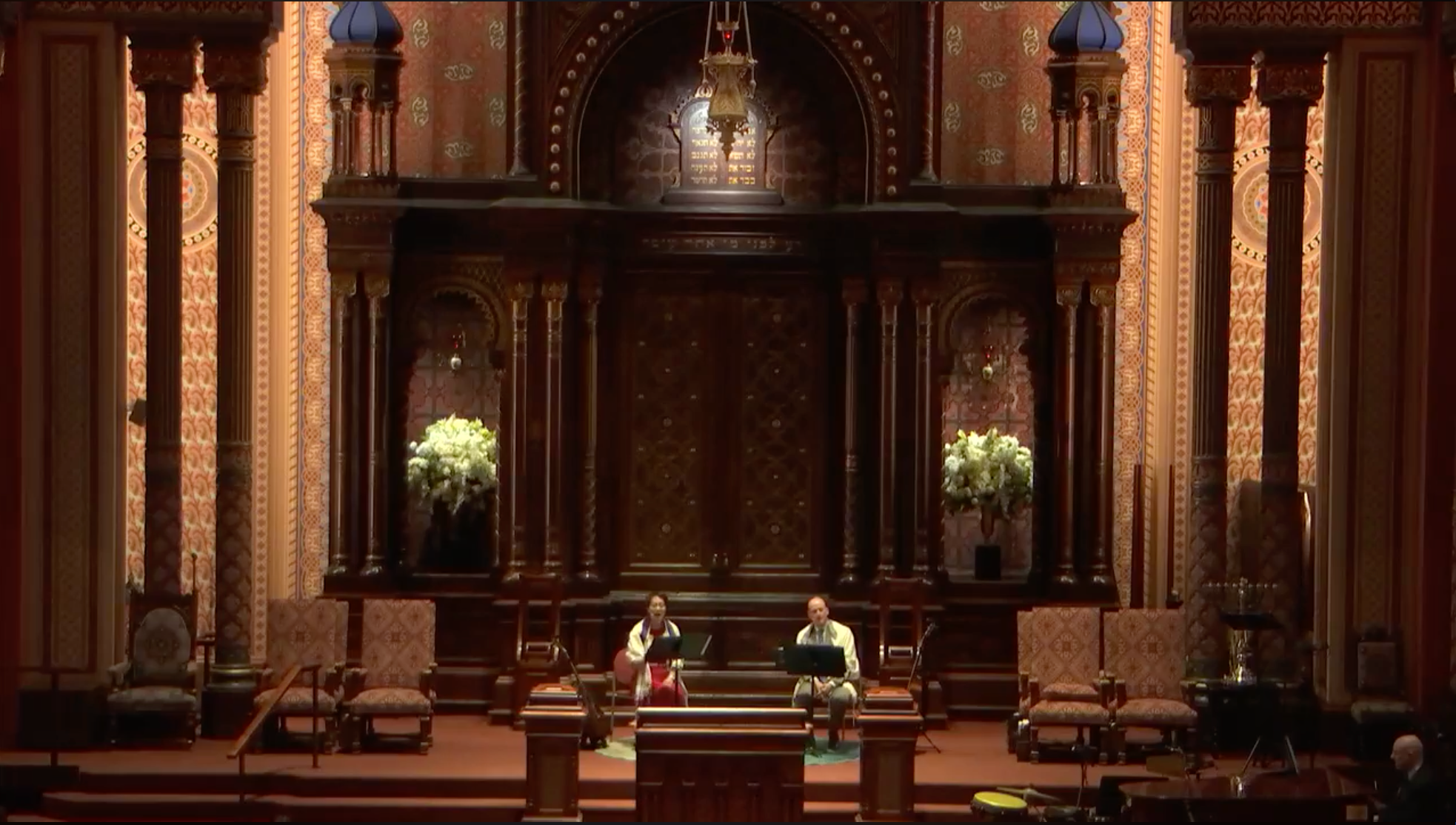

New York City’s Central Synagogue, seen here on March 21, 2020, launched an investigation last year of allegations against Sheldon Zimmerman, who served as its senior rabbi from 1972 to 1985. (Screenshot)

The current leadership of the congregation said it was never informed by the CCAR of the events that led to Zimmerman’s suspension in 2000. The leadership said it was “devastated” by the news and condemned Zimmerman for “a gross manipulation of his spiritual authority.”

My involvement and knowledge of these allegations began 20 years ago. I received a call in the spring of 2001 from a woman who identified herself at the time only as “Debbie.” She said she was the one who had approached the CCAR a year earlier with allegations about Zimmerman, dating back to her teenage years, that led to his resignation and suspension. She was calling me because she was upset that only a few months later, the rabbi had been named executive vice president of Birthright Israel, a move that was starting to cause controversy because of his recent misconduct.

She said she was torn between speaking out through a Jewish Week article or maintaining her public silence, but she clearly wanted to talk.

The woman asked if she could speak to me anonymously, and I agreed — an agreement that still holds today, though over time, and after extensive phone conversations, she revealed her true identity to me. Then as now, I also said I would not publish her story without her permission and would not reveal her identity.

The article I came close to publishing in 2005 would have included details of Zimmerman’s years-long relationship with Debbie, who first met him in the spring of 1970 when she was 15. As she described it to me, Zimmerman became her rabbi and teacher the following year when he was appointed assistant rabbi at Central Synagogue, and he soon began to relate to her in an inappropriate manner.

The article would have revealed that when she was 17 and studying privately with Zimmerman, who was 30 and married, he used Martin Buber’s “I and Thou” theology as a framework to explain or justify their intimate contact.

For the next decade, the nature of their relationship was a secret, given that their families were friendly and that she and her family viewed him as their rabbi, teacher and confidant.

The article also would have noted, for the first time and based on a copy of the committee’s never-released report obtained by The Jewish Week, that Zimmerman had an affair with at least one other woman, and that a CCAR investigative panel of its ethics and appeals committee found both women fully credible — and the rabbi far less so.

A ‘profound’ betrayal

I found Debbie thoughtful and articulate. She clearly had given much thought over the years to the unhealthy nature of the relationship that took place decades ago.

“What was so damaging is that this was the formative romantic relationship of my life,” she said at the time, adding that “the betrayal to me and my family was profound.” (Her parents were friends with Zimmerman and his wife.)

The story Debbie told me back then reflected her disappointment, frustration and anger with Zimmerman for being “manipulative — taking advantage of me and my being young and vulnerable — and for being untruthful.”

She also was upset with leadership in the organized Jewish community for focusing exclusively on the rabbi’s rehabilitation and reentry into Jewish public life without concern for the psychological and emotional damage done to her as a victim.

Debbie praised the CCAR investigating panel for its diligence in pursuing her allegations and, in effect, bringing down a major leader of the Reform movement. But she questioned why the gravity of Zimmerman’s violation of ethical and sexual boundaries did not seem to have been shared at least with other leaders within the Reform movement, which, it turned out, included HUC, Central Synagogue and the central body, now known as the Union for Reform Judaism, so others could be protected.

(In the wake of the 2021 Central Synagogue announcement, those other groups are launching their own investigations.)

Debbie first called me a few days after the announcement of the Birthright Israel appointment. She felt it was improper for the rabbi to be given a top position in an organization involving 18- to 26-year-olds. But she was wary of making her complaints public, concerned about “appearing vindictive” and fearful that her identity would become known.

Philanthropists Michael Steinhardt and Charles Bronfman, the co-founders of Birthright Israel, played a key role in hiring Zimmerman to help lead the organization professionally. In a news release announcing the appointment on April 5, 2001, Bronfman praised the rabbi as a “dynamic educator and leader whose talents will be a great blessing for Birthright Israel.”

Several years later Marlene Post, a lay leader of Birthright Israel who was one of several people who interviewed Zimmerman for the position, told me that “at that time we were unaware of the specifics” of his relationship. Post said she believed that the rabbi would not have been hired had the details been known.

Birthright Israel, which takes young Jews on trips to Israel, hired Sheldon Zimmerman as its executive vice president in 2001, months after he resigned as president of the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion. (Hadas Parush/Flash90)

All of this transpired at a different time. There was no #MeToo movement, and investigators habitually sought to protect the privacy of the accused as well as victims, and behaviors like “grooming” — in which someone in a position of trust and authority manipulates a minor for sexual purposes — were not part of the public vocabulary.

That put the burden on accusers like Debbie to convince the public that abuse had taken place. They also had a reasonable expectation that their accounts and character would be questioned. Meanwhile, Zimmerman was not only a leader of the Reform movement but a beloved spiritual leader and educator of great charm and charisma with a large and loyal following.

“I was single, I was very involved in my work and it seemed too risky to challenge him [the rabbi] publicly,” Debbie told me.

In the end, after much deliberation, she decided not to go public, and so did I. I agreed with Debbie that even revealing the contents of the CCAR committee report would have compromised her privacy, so I did not.

Readmitted to the CCAR

Four years later, Zimmerman was back in the news. After a brief stint at Birthright Israel, he had stepped down and held several non-pulpit posts, including two years as vice president of what is now the Jewish Federations of North America.

In 2005, after four years of suspension from the CCAR (two more than the original two years), the rabbi was readmitted to the Reform rabbinic group he once served as president.

Rabbi Janet Marder, then president of the CCAR, announced that following a “rigorous process” of counseling and mentoring, Zimmerman met all the requirements outlined and was reinstated to full membership. She said the CCAR board made the decision based on the recommendation of the committee on ethics and appeals.

That decision prompted Debbie to be back in touch with me. She felt his reinstatement was unearned, and she blamed the CCAR for not living up to the rules of its own ethics and appeals committee. These include “the making of restitution” and offering “an acceptable expression of remorse” with specificity of wrongdoings to all of those harmed, according to the guidelines.

“He should have been expelled, not suspended” by the CCAR, Debbie told me at that time, asserting, as is clear from the committee’s private report, that the rabbi did not admit to the nature of their relationship or the fact that he had relations with another woman until he learned that the CCAR committee already knew the facts.

“What kind of teshuva [repentance] is it,” she asked, “when he has advanced his career by lying about what he did?”

Debbie said she received no compensation for the therapy she underwent — only airfare to attend a meeting with the ethics committee. Zimmerman wrote an apology to her that she said was impersonal and did not take full responsibility for his actions. She felt he should have apologized to her family and others who were hurt or misled, and should have initiated a personal meeting with her without being prompted.

“That’s what a wrongdoer has to do,” Debbie told me. “It’s easy to say ‘I made a mistake,’ but it’s hard to say that directly to the victim.”

She criticized the ethics committee for allowing the rabbi to make his apology in writing rather than face to face.

“The process of teshuva should be a dynamic between people,” she told me, “but it’s been between the CCAR and him.” Debbie said she resented being left out of the process.

In a response to my queries in 2005, Zimmerman emailed me to say that an expert who was counseling him as part of the reinstatement process warned him against having any personal contact with Debbie. He maintained that his letter was “an act of teshuva,” and went on to point out that he had more than fulfilled the CCAR requirements for readmission.

Accusing Debbie of seeking revenge, he stated: “My career has been seriously damaged. This is about destroying me and my family. I have met every teshuva requirement, both of the CCAR and the tradition itself. She has made none to my wife and family, and in fact quite the opposite.”

Zimmerman threatened to out Debbie without her consent, telling me, “She may leave us no recourse but to respond to her in public and by name, and to lift the veil that has protected her and her actions.”

(On May 11, I sent an email to Zimmerman telling him I was working on this follow-up to Central Synagogue’s investigation, and that I would like to speak with him or get a statement from him with his response to the investigation and its findings. He has not replied.)

Soon after contacting me again, Debbie again decided, reluctantly, not to go public, fearful of public exposure and a possible lawsuit.

So the matter remained until it boiled up again last month with the Central Synagogue letter to its congregants and a report in the Forward.

Returning to the story

Debbie texted me two days before the Central Synagogue letter was made public last month. She was under the impression that I was writing an article on the latest development, but that wasn’t the case. In fact, I was unaware of it until I spoke with her the next day and she brought me up to date. Now that the Zimmerman chapter had been reopened, she was committed to having her story known — under the same conditions we agreed to more than 20 years ago, that her identity remain private.

“I’ve wanted at least the basic fact of my youth and his predatory conduct to be known,” she told me. “But Zimmerman put a lid on it by threatening me with litigation and [with] revealing my identity.”

Central Synagogue and others are faulting the CCAR for not sharing the extent of its findings with colleagues, even within the movement, and the organization is undergoing its own reexamination of practices now. But the CCAR’s policies two decades ago on dealing with sexual impropriety among its clergy were praised at the time, and many saw its decision to take action against Zimmerman as courageous.

To me, the episode underscores the difficulty, if not impossibility, for any peer group to pass judgment on one of its own, and suggests why experts in the field recommend that outside investigators probe misconduct at this level.

It also underscores the ways in which Jewish concepts about repentance may figure into #MeToo episodes in our communities.

Zimmerman insisted that he fulfilled more than the requirements for teshuva, including therapy, apology and time for self-reflection. But Debbie told me earlier this week that “at the heart of the issue” for her, even now, is whether the rabbi “could actually see the person he has wronged and understand how he harmed me.” That did not happen, she said.

In preparing this piece, I went back and found my “Zimmerman file,” a thick collection of printed out emails, notes of conversations with Debbie going back 21 years and a number of others, including Zimmerman. It took me nearly two hours to read through it all.

On the page that contained the rabbi’s email to me, cited above, I had written a note to myself: “Am I obligated to hold the story if she gets cold feet?”

That was the question I grappled with in 2001 and again in 2005. It seemed to pit journalistic responsibility against compassion for a self-described “damaged” victim of an abusive relationship. In the end, I felt that to tell Debbie’s story without her permission would be one more violation of her personal freedom.

Now, 21 years after we first spoke, I reviewed the contents of this article with her before publication to ensure its accuracy.

Gary Rosenblatt was editor and publisher of The Jewish Week from 1993 to 2019. Follow him at garyrosenblatt.substack.com.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.