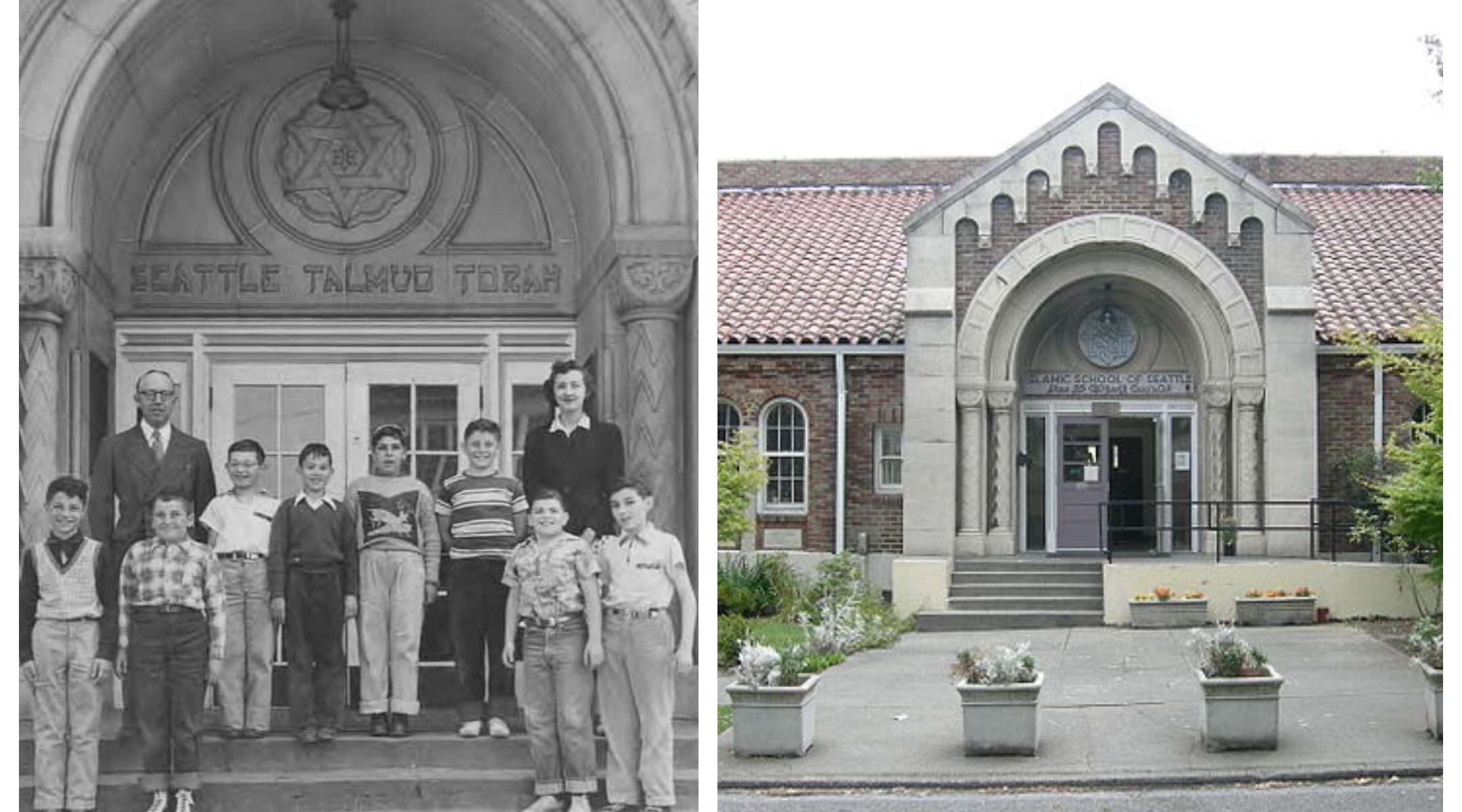

(The Cholent via JTA) — Nearly 100 years after Seattle’s first Jewish school opened, an effort is underway to restore its crumbling building — as a multifaith center that can unite Jews and Muslims in the city.

So far, the effort has netted more than $40,000 toward a new roof for the building that once housed Seattle Talmud Torah. But that’s a drop in the bucket for what a growing collective of Seattleites are hoping to generate to turn the Cherry Street Collective into a reality.

“We’ve got lots of plans,” Cherry Street Village project manager Koloud “Kay” Tarapolsi said. “The only thing holding us back is our imaginations.”

The building’s story begins in 1928, when Seattle Talmud Torah’s president, Fred Bergman, implored readers of the Jewish Transcript, then Seattle’s Jewish newspaper, to invest in Jewish education.

“United we shall build a new Talmud Torah, dedicated to God and Israel,” Bergman wrote. “Out of these portals there will emerge healthy, upright and loyal Jews, proud of their heritage, Jews with a Conscience.”

By 1929, money had been raised — $1,000 for a plot of land at Columbia and 25th in Seattle’s Central District — and the esteemed Scottish Jewish architect B. Marcus Priteca was on board to build an institution for Jewish learning. The Seattle Talmud Torah was born.

Over time, the Jewish community’s educational needs changed, and the Talmud Torah disbanded in 1962. In 1980, the building was sold to the Islamic School of Seattle. The school disbanded in 2012, and the space was refashioned as the Cherry Street Mosque.

Nearly 100 years after it was built, the building that the Jewish community rallied for now sits in disrepair. Its roof leaks, rooms flood and black mold plagues the interior. The mosque community could have walked away and probably could have sold the entire plot to an eager developer.

Instead, the community decided to save it.

But repairing the roof and just getting rid of the mold proved too big a project for the small group. So in November, a coalition called Cherry Street Village launched a fundraiser to repair the building and repurpose the space as a multifaith collective.

“It started as a group of friends, and now it’s expanding,” Tarapolsi said.

The group now includes the Salaam Cultural Museum, Dunya Theater Productions, Kadima Reconstructionist Community and Middle East Peace Camp.

Jonathan Rosenblum has been involved with Kadima for 20 years and is the Kadima liaison to the village. Aware that the Jewish group is outgrowing its space (a church it rents in Madrona, less than a mile away), Rosenblum turned to Cherry Street leaders, with whom Kadima already had a relationship.

“We realized there was this beautiful architecture, a cavernous hall … one could imagine what it would be like to be together in community,” Rosenblum said. “We committed to work together to get the roof repaired. There’s been an outpouring of support, which has been amazing.”

Tarapolsi has big dreams for Cherry Street Village — artists in residence, social services and food trucks. She imagines an apartment for visiting artists, rooms for rent, a place for social services. A sculpture garden. A community garden. And religious events for both religions — b’nai mitzvah, Ramadan nights, prayer services and beyond.

Jews and Muslims under one roof? It’s happened before: in a neighborhood in Paris, a school in London, a synagogue in New York City.

In the context of what’s happening in Seattle, the space sharing is especially easy to imagine. Both Kadima and Cherry Street Mosque are on the progressive end of their respective religious traditions. Kadima prides itself on a social justice agenda and solidarity with the plight of Palestinians, which sometimes puts it “outside the tent” of the mainstream Jewish community.

Cherry Street is unique among Muslims, too. The Islamic School of Seattle was started by five American women who wanted a progressive, Montessori-style Muslim school.

“We had children come from all different families,” said Laila Kabani, a disciple of the school’s founder, Ann El-Moslimany. “It was really an interfaith school.”

El-Moslimany died in January, but she is revered as an educational pioneer. (Read Kabani’s heartfelt memorial to her mentor here.) The mosque is a rarity in that it has a female imam.

“Around 99.99% of the other mosques wouldn’t have a female on the board,” Tarapolsi said. “It’s very, very progressive. We’re very unique and we’re open to everyone, no matter the sexual orientation, skin color, etc.”

Kadima leaders say the mosque’s unique orientation is crucial for their relationship.

“That aspect of the progressive stance is an important connector,” Doug Brown of Kadima said. “I think most of us share the perspective that we grow and understand our traditions better when we’re in conversation with folks from other traditions. … The issues we want to address require broad coalitions.”

Brown’s wife, Sandy Silberstein, has been heavily involved with building bridges to Muslim communities and the Middle East Peace Camp, which is allied with Kadima. The camp brings together children from Jewish, Muslim, Arab, Israeli and Christian backgrounds every summer with the intention of building relationships and understanding.

“We know that when Islamophobia and antisemitism hit, we have each others’ backs,” Silberstein said.

The collective has held one event, a virtual cooking demo with a Palestinian chef. Baking date cookies is pretty low stakes, but what if conflict does arise in the future among the partners?

“In any relationship there’s going to be conflict; it’s how you manage it,” Rosenblum said. “We wrestle with that stuff. We are wrestlers with God. We work with people through this conflict. When you look at all the conflict going on, not just in Seattle but throughout the world, the most important thing we can do for the younger generation is model how we should behave toward each other.”

But first things first. And that’s the roof.

“The first step is to get the rain to stop coming in,” Rosenblum said.

For Kabani, Cherry Street Village is a continuation of the legacy of El-Moslimany.

“She passed away, but her spirit lives on,” she said. “Cherry Street Village intends to continue the joy and diverse faiths under one roof.”

A version of this story was originally published in The Cholent, an independent newsletter about Seattle’s Jewish community.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.