(JTA) — In the late 1800s, the Ottoman Empire was looking to conscript men into its army, including the several thousand young Jewish ones who were living in the city of Baghdad.

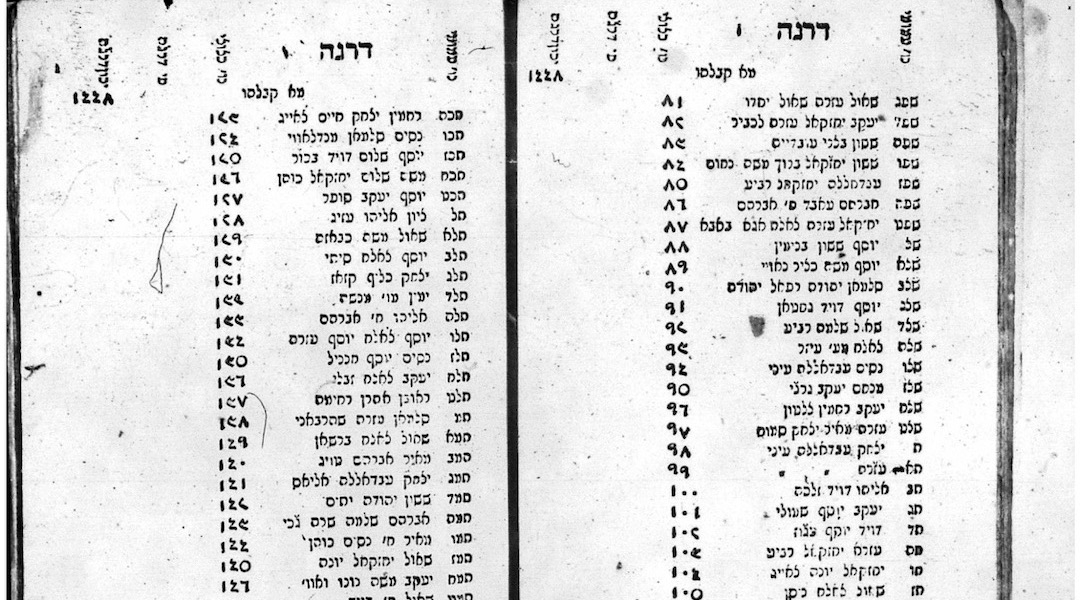

The Jewish community didn’t like the idea of the imperial forces taking away its young men, so it arranged to pay authorities for exemptions. Rabbi Shlomo Bekhor Husin of Baghdad documented the exemptions, carefully jotting each down name in medieval Rashi script.

In the following decades, many of those names vanished or morphed as the Jews living there dispersed across the globe. But the lists survived and now are housed at the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem — if you’re willing to deal with the microfilm format on which they are preserved.

Retired Israeli diplomat and independent researcher Jacob Rosen-Koenigsbuch has squinted to read and translate every single one of the nearly 3,500 names on Husin’s lists. And the lists are just one of the dozens of idiosyncratic sources that Rosen-Koenigsbuch has consulted in his years-long hunt for lost Jewish family names.

Rosen-Koenigsbuch, 73, has published the world’s most complete lists of Jewish surnames from the cities of Baghdad, Damascus, Cairo and — as of this week — Alexandria. (Next up are probably Basra, Mosul and Erbil, he said.) The four lists, first published by the genealogy website Avotaynu Online, have been combined by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency into this searchable database. (If you know your name belongs but isn’t there, email Rosen-Koenigsbuch, who’s always making additions and corrections.)

Before I spotted Rosen-Koenigsbuch’s research on the internet, I had only once ever seen a written reference to my family’s original Baghdadi last name. The generically Israeli sounding “Shalev” was “Shaloo” until my grandfather changed it upon moving from Iraq to Israel in 1951. An act of assimilation, the switch was easy because “Shalev” and “Shaloo” are spelled the same in Hebrew script: shin-lamed-vav. The letter “vav” is capable of making both an “oo” sound and a “v” sound.

I searched and found no “Shaloo” on Rosen-Koenigsbuch’s list. But I did find a “Shellu,” and it felt close enough. Maybe, I thought, that was just how he had transliterated a name that could be spelled out any number of ways.

“One of the biggest problems in this work is transliteration,” Rosen-Koenigsbuch said on the phone from Jerusalem as he began to confirm my inkling. “There are different ways to pronounce the names and different ways to spell them.”

I asked him where he had found “Shellu.” He pulled up his sources and quickly told me that the name appeared three times. First, he told me about Husin’s Ottoman exemptions, and among them was a young lad with the name spelled “shin-lamed-vav.” Shellu. Shaloo. Shalev. Bingo. This could be a forgotten ancestor.

Then, he said the name appeared twice in a 1950 registry from Iraq. This was a list of people whose citizenship was revoked during the Iraqi Jewish exodus — definitely my ancestors. After years of curiosity, and some research, I had finally made a genealogical breakthrough.

Rosen-Koenigsbuch started on the surnames project while doing his own genealogical research. But his family is not from the Middle East; they’re from Poland.

“My parents were Holocaust survivors,” he said. “And they didn’t speak. My father was completely silent.”

To learn anything about his family’s past, he had to dig.

He discovered elaborate family connections and eventually gave lectures on his findings. Audience members with Mizrahi heritage would approach him and they tended to have a certain reaction.

“I would hear this mantra,” he said. “We don’t know anything about our families because we left Egypt or Syria or Iraq in a hurry. We left everything behind and the archives are closed. We came out alive from those countries, but the documents are not with us. In Europe, most of the Jews were annihilated but the archives are open.’”

Rosen-Koenigsbuch, who served as Israel’s ambassador to Jordan from 2006 to 2009, had the geographic interest and some of the linguistic knowledge to find out what kind of information might still exist despite the lacunae.

He decided to focus on surnames and found thousands of them in historic newspapers, business directories, a circumcision registry, court records, previously published research and through the help of social media groups dedicated to the various Jewish diasporas.

None of these sources are comprehensive. Your family was more likely to be mentioned somewhere, for example, if you donated money or if you sent your kids to Jewish schools.

“There are many limitations, but we have to try to gather the history because we still have among us people in their 70s, early 80s and in 10 years there will be no one to talk to,” Rosen-Koenigsbuch said. “If we will not hurry they will be gone. It’s a very important message to encourage people to start thinking about this.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.