ATLANTA (JTA) — To the end of his life, the civil rights hero and later congressman John Lewis remembered the half-mile walk from his family’s farm in rural Pike County, Alabama, to the Dunn’s Chapel School.

There was no school bus for Black children; Lewis’ hike was short compared with the miles walked by many of his classmates. They were being educated in surroundings separate from whites, but hardly equal.

The school was a small, wooden, whitewashed building with a large window. An interior wall partitioned the space into two rooms, heated by potbelly stoves, burning wood that students fetched from a nearby forest. Water was drawn and carried from a farmer’s well up the road.

Dunn’s Chapel was a “Rosenwald school,” one of nearly 5,000 such schools built across 15 Southern states from 1912 to 1932. This effort was an outgrowth of a collaboration between Julius Rosenwald, the son of German Jewish immigrants and a leading philanthropist of his time, and Booker T. Washington, the renowned educator born into slavery in Virginia.

In the years they operated, Rosenwald schools educated one-third of rural Black children in the South, an estimated number of more than 663,000 students. Lewis was one. Others included writer Maya Angelou, civil rights activist Medgar Evers, and playwright and director George Wolfe. A study published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago found that the educational gains by Rosenwald school students spurred many Black young adults to migrate north, and those who remained in the South had wage gains over their peers who did not attend the schools.

The Rosenwald schools closed several decades ago, a process accelerated by the landmark 1954 Supreme Court ruling that racially segregated, “separate but equal” schools were “inherently unequal” and violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment of the Constitution.

Of the roughly 10% of the schoolhouses that remain, some have been repurposed as museums or community centers, while others have decayed with the passing years. A small number still operate as schools.

A portrait of Rosenwald hanging at the Noble Hill School in Georgia’s Bartow County, another of the Rosenwald schools. (Andrew Feiler)

Atlanta-based photographer Andrew Feiler, a fifth-generation Georgian Jew, has spent several years traveling throughout the South documenting what remains of the school sites. Now the images have been compiled in his book “A Better Life for Their Children: Julius Rosenwald, Booker T. Washington, and the 4,978 Schools that Changed America,” published this month by University of Georgia Press. Lewis authored the foreword not long before his death in July from pancreatic cancer at age 80.

The 136-page book, featuring 85 black-and-white images, is the product of 3 1/2 years of research — and 25,000 miles of driving. Feiler photographed 105 of the structures that once housed Rosenwald schools, along with some of the men and women whose lives were changed by the education they received in their classrooms.

“It simply became imperative that I share these stories as part of this endeavor, so each image or pair of images comes with a narrative written by me,” the 59-year-old Feiler said. “This is a book of photography, but it is also a book of stories.”

Rosenwald, who was born in 1862 and died in 1932, was part owner and president of Sears, Roebuck & Co., back when the Sears, Roebuck mail-order catalog was the Amazon of its day. As a member of Chicago Sinai Congregation, he was influenced by the social justice teachings of Rabbi Emil Hirsch, one of which held that “property entails duties.”

For his part, Rosenwald believed that Jews should uniquely sympathize with the plight of African-Americans.

“The horrors that are due to race prejudice come home to the Jew more forcefully than to others of the white race, on account of the centuries of persecution which they have suffered and still suffer,” he said.

In 1912, a couple of years after reading Washington’s autobiography, “Up From Slavery,” Rosenwald met its author, the founder of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (today called Tuskegee University). Together they set out to change the educational landscape of the region.

Rosenwald personally invested $4.3 million — more than $80 million in today’s currency — to construct the schools. In varying ratios over the years, matching funds came from the Black community and white-controlled governments.

Rosenwald’s philanthropic philosophy was “give while you live,” believing that a foundation should expend its funds within a predetermined period. To that end, he stipulated that the Rosenwald Fund, created in 1917 to support the schools and his other philanthropic projects, should cease operations within 25 years of his death.

By the time the fund stopped operating in 1948, some $70 million (equaling more than $700 million today) had been spent benefiting schools, colleges and universities, Jewish charities and institutions serving the Black community. Recipients of Rosenwald-funded fellowships included singer Marian Anderson; poet Langston Hughes; authors James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison and W.E.B. Du Bois; diplomat Ralph Bunche; photographer Gordon Parks; and choreographer-dancer Katherine Dunham.

The fund also financed early litigation by the NAACP, the nation’s oldest civil rights organization, that led to the historic Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka making integrated education the law of the land. The decision also began the close of the era of the Rosenwald schools.

Photographer Andrew Feiler at the Carver School in Coffee County, Ga., working on his project documenting the sites of former Rosenwald schools. (Jim Cottingham)

Despite some recent efforts to tell the story of the Rosenwald schools, including the 2015 documentary “Rosenwald,” it remains a lesser-known piece of American history. That’s what attracted Feiler to the project.

Feiler spoke to Jeanne Cyriaque, a historian of African-American culture, and she detailed her efforts to preserve what remained of the Rosenwald schools.

As the African-American Programs coordinator for Georgia’s Historic Preservation Division, Cyriaque sought out the oldest structures in Black communities in the state’s 159 counties.

“In that quest I would ultimately become a preservationist of remaining [Rosenwald] schools and an advocate for documenting their powerful stories of African American achievement in education,” she wrote in a contribution to Feiler’s book.

Feiler said the story of the schools “shocked me.”

“How could I [have] never heard of Rosenwald schools? The pillars of this story — Jewish, Southern, progressive, activist — these are the pillars of my life,” he said. “That afternoon I sat at my desk in Atlanta and Googled ‘Rosenwald schools.’ I quickly found there were a few books on the topic, but there was no comprehensive photographic account. I set out to create exactly that.”

Feiler, a Savannah native, began taking photographs as a 10-year-old, wielding a Kodak Instamatic. His avocation has since become a vocation.

“Starting in mid-2008, I went through 4 1/2 very difficult years — the death of a business partner, near-death of my brother, health collapse of my father and over three years of real estate workouts during the Great Recession,” he said. “Collectively these experiences caused me to ask what I wanted to do with the rest of my life. I still manage our family real estate business, but I now do it part-time.”

His first book, published in 2015, was “Without Regard to Sex, Race, or Color: The Past, Present, and Future of One Historically Black College” (University of Georgia Press), a tour of abandoned classrooms and facilities at Morris Brown College in Atlanta. The school, on the city’s west side, emerged relatively recently from bankruptcy and is seeking reaccreditation.

Feiler’s latest work was influenced artistically by the early history of the Rosenwald schools, specifically a pilot project built near Tuskegee.

“Washington sent Rosenwald photographs of the children and teachers proudly gathered in front of their new schools,” Feiler said. “These deeply moved Rosenwald and contributed to his support for expanding the program. Making such photographs became common, and they are a prominent visual element of the program’s history.”

Feiler usually works in color, “but I found this history so compelling that I decided to pay homage to these historical images and shoot my Rosenwald schools work entirely in black and white and horizontal,” he said.

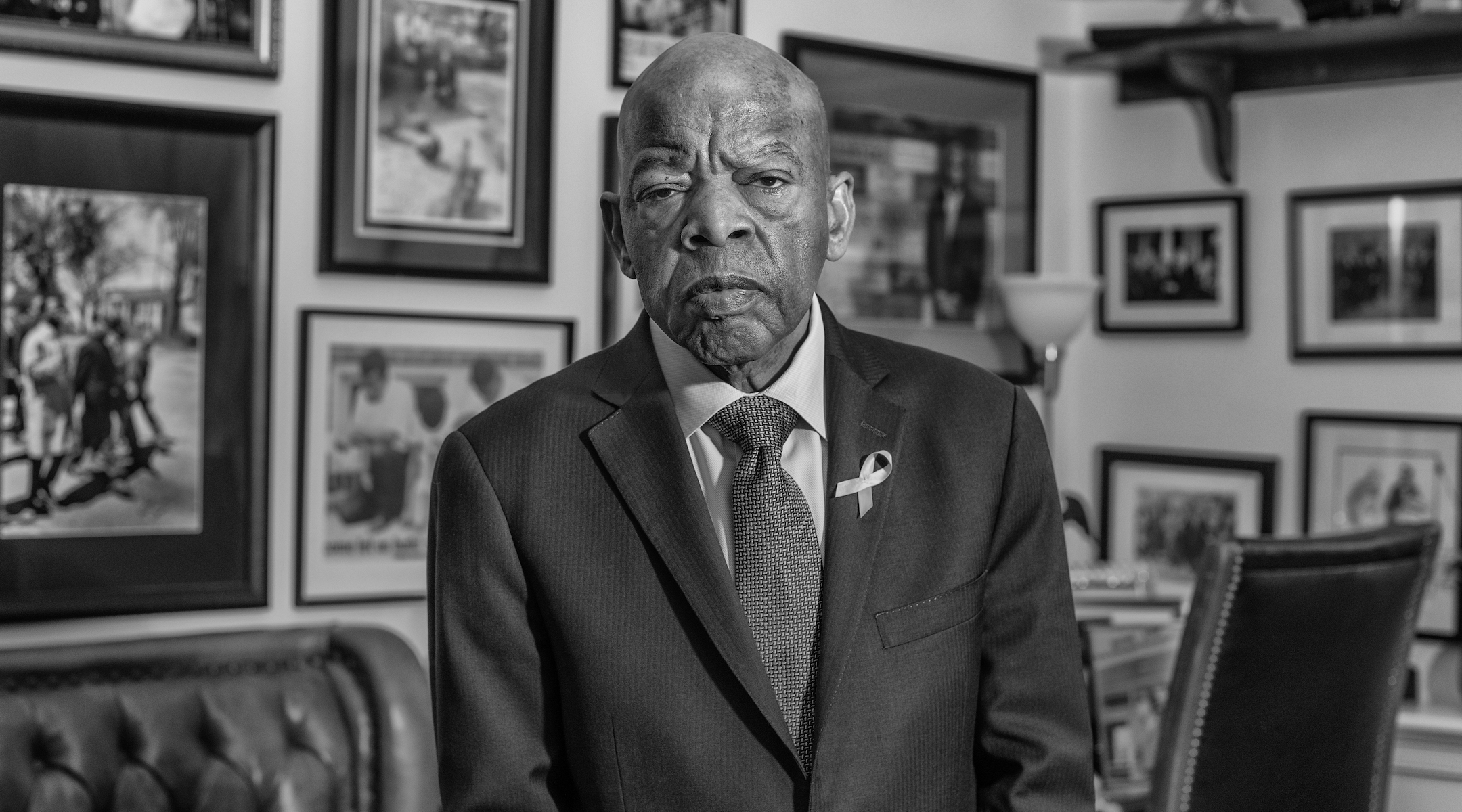

Rep. John Lewis, who represented Georgia’s 5th District for 33 years before his death in 2020, attended a Rosenwald school as a child. (Andrew Feiler)

Feiler hopes his book can add to the steps that have been taken to preserve Rosenwald’s memory. In 2002, the National Trust for Historic Preservation declared the Rosenwald schools a National Treasure, placing them on its list of Most Endangered Places and providing assistance “to help save these icons of progressive architecture for community use.”

On Jan. 13, the day that he was impeached by the House of Representatives, President Donald Trump signed the Julius Rosenwald and the Rosenwald Schools Act of 2020, which directs the Department of the Interior to study the sites of the former schools for preservation. It’s a first step toward creating a multistate national park that would include some of the surviving schoolhouses and a visitors center in Chicago. Backers say it would be the first national park site to honor a Jewish American.

The Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation has erected markers acknowledging the role played by the Jewish philanthropist at Tuskegee University in Alabama, and at the sites of Rosenwald schools in Warrenton and Rectortown, both in Virginia.

Rosenwald and Washington’s shared vision changed the educational landscape of the South and expanded the horizons for generations of students. That certainly was the case at the Dunn’s Chapel School, where the young John Lewis loved to read biographies and learned “that there were black people out there who had made their mark on the world,” as he wrote in the foreword to “A Better Life for Their Children.”

The structure itself may have been basic in design and lacking amenities, but as Lewis remembered: “It was beautiful, and it was our school.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.