(JTA) — Open the pages of an early printed Talmudic text and you are likely to encounter the florid signature of Domenico Gerosolimitano. Why did he leave his personal autograph on so many precious volumes?

Domenico was no studious rabbinic sage bent over the Talmudic page, nor an enthused Jewish bibliophile happy to run across these sacred works. He was a Christian censor. His task was to edit the Jewish religion, striking out any terms or ideas that the Catholic Church deemed too harmful or problematic for their liking. His job was telling members of another faith what they could and could not do with their religion, and his autograph meant that a volume merited his all-important approval.

It’s a role that a surprising number of today’s Jews seem to aspire to this week in response to the growing phenomena of Christian seders. These “seders,” organized by and for Christians, borrow from Jewish Passover traditions for the purpose of Christian teaching and celebration. Typically they make reference to the most well-known Passover meal in history — the Last Supper. You can find a wide range of guides and instructions online, each offering their own ritual and spin. Passover may be the festival of unleavened bread, but these seders are on the rise.

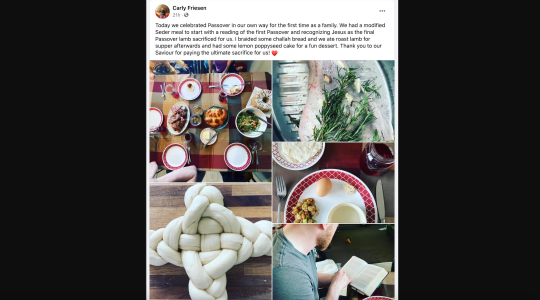

As is a torrent of online outrage from Jewish voices. A viral tweet critiquing one Christian woman’s seder photos gained national news attention with its acerbic remark: “I think I just had a rage blackout.” Further didactic responses followed and were widely shared, like: “Hebrew school teacher here, and I’d like to offer my services to Christians wanting to lead a Passover Seder! Just follow these 4 easy steps: 1) Don’t 2) F*cking 3) Do 4) It.”

The self-righteous disapproval of other people’s private religious practice reflects a disturbingly illiberal axiom: that what other people do in their own homes, with their own family, in accord with their own beliefs, is somehow harmful to me. Many Jews were particularly upset to see these seders feature oddly inaccurate symbols, like a centerpiece challah in the shape of a cross.

Strange? Sure. It is uncomfortable to see familiar signs employed in unfamiliar ways — but no one is forcing us to look. Invoking Jesus at a church basement seder table feels like something precious has been pilfered, but no actual Jewish practice is thereby diminished. Passover challah is a contradiction in Jewish terms, not in human ones.

The truth is that each religious tradition runs on its own internal logic. I don’t expect Christians to understand the complex poetry of rabbinic Judaism, and I would fight like a Maccabee before letting their nosy inspectors decide which trends in Jewish practice are or are not kosher. We enter the terrain of retrograde culture warriors when we insist on regulating our neighbors’ dinner parties. It makes sense to them – can’t that be enough?

Many would argue no. A common concern is that Christian seders inappropriately veer from the “authentic” seder message. In reality, every year sees the development of new seder insights and experiences. Jews today celebrate feminist seders, social justice seders, gun control seders and political parody seders. You can find the Hogwarts Haggadah, the Seinfeld Haggadah, Zionist Haggadahs, anti-Zionist Haggadahs, and hundreds of works featuring the novel comments of contemporary scholars and thinkers. Travel back in time to the night on which Rabbi Akiva and his colleagues spent the evening discussing the Exodus, and I am confident their conversation would be far different than most Jewish seders today.

Of course, not all “new” interpretations of the seder are correct or wise, and I certainly believe that a Christological read of the seder reverberates with theological untruth. But that’s because I don’t believe in Christianity — ever — not because there is some preciously “correct” version of the seder that I dare not move past. If you object to a MAGA seder, do it because you disagree with Trump, not because you insist seder in 2021 must still be sponsored by Maxwell House.

Finally, many decry Christian seders as an act of cultural appropriation, as it so explicitly borrows elements of Jewish culture for its own use and needs. The great irony of this critique is that the seder itself borrows remorselessly from a previous cultural touchstone: the Greco-Roman symposium. The most glaring example is the “afikoman,” itself a Greek loan word meaning, roughly, dessert. The structured evening of food, wine and discussion is a direct appropriation of the symposium style, and even classic seder ingredients like karpas, charoset, sandwich making, reclining and handwashing are all a play on Greco-Roman ritual.

Of course, the Sages that constructed the seder were not interested in imitating every value and step of the Greco-Roman practice. Philosophizing was replaced with Torah study; the “dessert” of a hedonistic afterparty became the more tame afikoman and Hallel that we know today. The structure remained while the message was altered. It is the brilliance of Jewish tradition to appropriate ritual structures not our own, imbue them with new meaning and, within our own spaces, employ them for our own spiritual and communal purposes.

There is a temptation to edit out elements of other religions that we find distasteful. Domenico Gerosolimitano knew it well. Born a Jew, with years of rabbinic study under his belt, and later a convert to Christianity, he had all the Hebrew literacy and knowledge necessary to draw up the Church’s official list of problematic, harmful, offensive Jewish texts.

Moving past a world full of interreligious nitpicking requires more than just limiting the power of the censor’s hand. It also means working past the restricting, condescending instinct of a censor’s mind.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.