(JTA) — George Segal, whose career as an actor ranged from shattering Jewish stereotypes in his youth to cheerfully indulging them in his dotage, has died at 87.

The fact that early in his career Segal had to field questions about why he didn’t change his name or fix his nose was a testament to how unusual it was at the time for a Jewish actor who could play a plausible tough guy and romantic lead to present as Jewish.

“I didn’t change my name because I don’t think George Segal is an unwieldy name,” Segal told The New York Times in 1971. “It’s a Jewish name, but not unwieldy. Nor do I think my nose is unwieldy. I think a nose job is unwieldy. I can always spot ’em. Having a nose job says more about a person than not having one. You always wonder what that person would be like without a nose job.”

Segal’s meld of defiance and self-deprecation helped pave the way for actors like Elliott Gould, Dustin Hoffman and Richard Benjamin. The days of Jewish actors and actresses like John Garfield and Lauren Bacall changing their names in order to present as desirable were over.

Segal brought sex and athleticism to his 1966 role as a naive academic caught in a trap by a destructive couple in “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” Segal played opposite Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton in the film, which earned him his only Academy Award nomination.

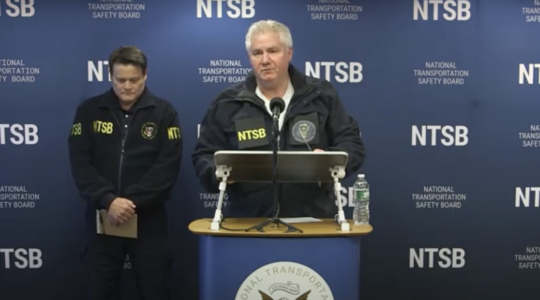

George Segal and Barbra Streisand in a still from the 1970 movie “The Owl and the Pussycat.” (FilmPublicityArchive/United Archives via Getty Images)

His roles were soon Jewish as well, in films like “Bye Bye Braverman” in 1968 and “Blume in Love” in 1973. In 1970, he shattered Jewish stereotypes in “The Owl and the Pussycat,” where he starred opposite Barbra Streisand.

His most emblematically Jewish role from that time was not obviously Jewish: He played the eponymous hero in the 1966 spy thriller “The Quiller Memorandum,” tracking down a ring of postwar Nazis. Harold Pinter, the Jewish playwright who wrote the screenplay, reshaped the laconic British spy in Elleston Trevor’s novel into an American furious at Europe for allowing the Nazis to flourish and for never truly crushing them.

George Segal kicks a man in a scene from the film “The Quiller Memorandum,” 1966. (20th Century Fox/Getty Images)

“Nobody wears a brown shirt now, no banners, you see,” Quiller’s British handler, played by Alec Guinness, tells him. “Consequently, they’re difficult to recognize, they look like everybody else.”

Quiller is ultimately betrayed (spoiler alert) by his young German girlfriend. He is captured by the Nazis and resists their torture to escape. He meets with his handler and they have a Pinter-esque exchange that alludes to the postwar anomaly of being Jewish in a continent that has made Jews disappear.

“Met a man called Oktober,” Quiller says of his encounter with the head Nazi. “At the end of our conversation, he ordered them to kill me.” The handler rejoins: “And did they?”

Segal continued to play romantic leads, notably teaming up with Glenda Jackson in “A Touch of Class” in 1973. He filmed the crime caper classic, “The Hot Rock,” opposite Robert Redford, in 1972, and joined with Elliott Gould in 1974 in “California Split,” considered one of the best gambling films ever.

His career went into a downward spiral in the early 1980s, fueled by what he said was self-destructive behavior, including drugs. His rehabilitation included touring with a band he led with his banjo, the Beverly Hills Unlisted Jazz Band. In an appearance with the band in Israel in 1982, he was welcomed as a hero.

Segal played minor roles and then reemerged in 1996 in a role as Ben Stiller’s father in “Flirting with Disaster.” That character would define the rest of his career: the neurotic, self-effacing Jewish dad. It was a role he replicated in the television sitcoms “Just Shoot Me!” (albeit as an ostensible Italian) and “The Goldbergs,” from 2013 until now.

Actors Wendi McLendon-Covey and George Segal attend an event celebrating the 100th episode of “The Goldbergs” in Culver City, Calif., Oct. 4, 2017. (Rich Polk/Getty Images for Sony Pictures Television)

Segal was born in 1934 in New York. He is survived by two daughters, Polly and Elizabeth, from his first marriage to Marion Sobel, and his third wife, Sonia Schultz Greenbaum, a high school girlfriend with whom he reunited after the death of his second wife, Linda Rogoff. Sonia said Segal died of complications following bypass surgery.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.