This interview first appeared in the Jewish Week.

Ivanka Trump and Monica Lewinsky were both compared to Queen Esther. Hillary Clinton called the star of the Purim story her favorite biblical heroine. In 1862, an abolitionist minister quoted the Book of Esther in calling on President Lincoln to free the slaves.

Those are just a few of the ways the Book of Esther has been deployed in American political and cultural life. Ministers, rabbis, politicians, activists, feminists, anti-feminists and more have drawn on the story of the Jewish queen in the court of the Persian King Ahasuerus, finding lessons in how she intervenes to prevent the king’s evil minister Haman from killing the kingdom’s Jews.

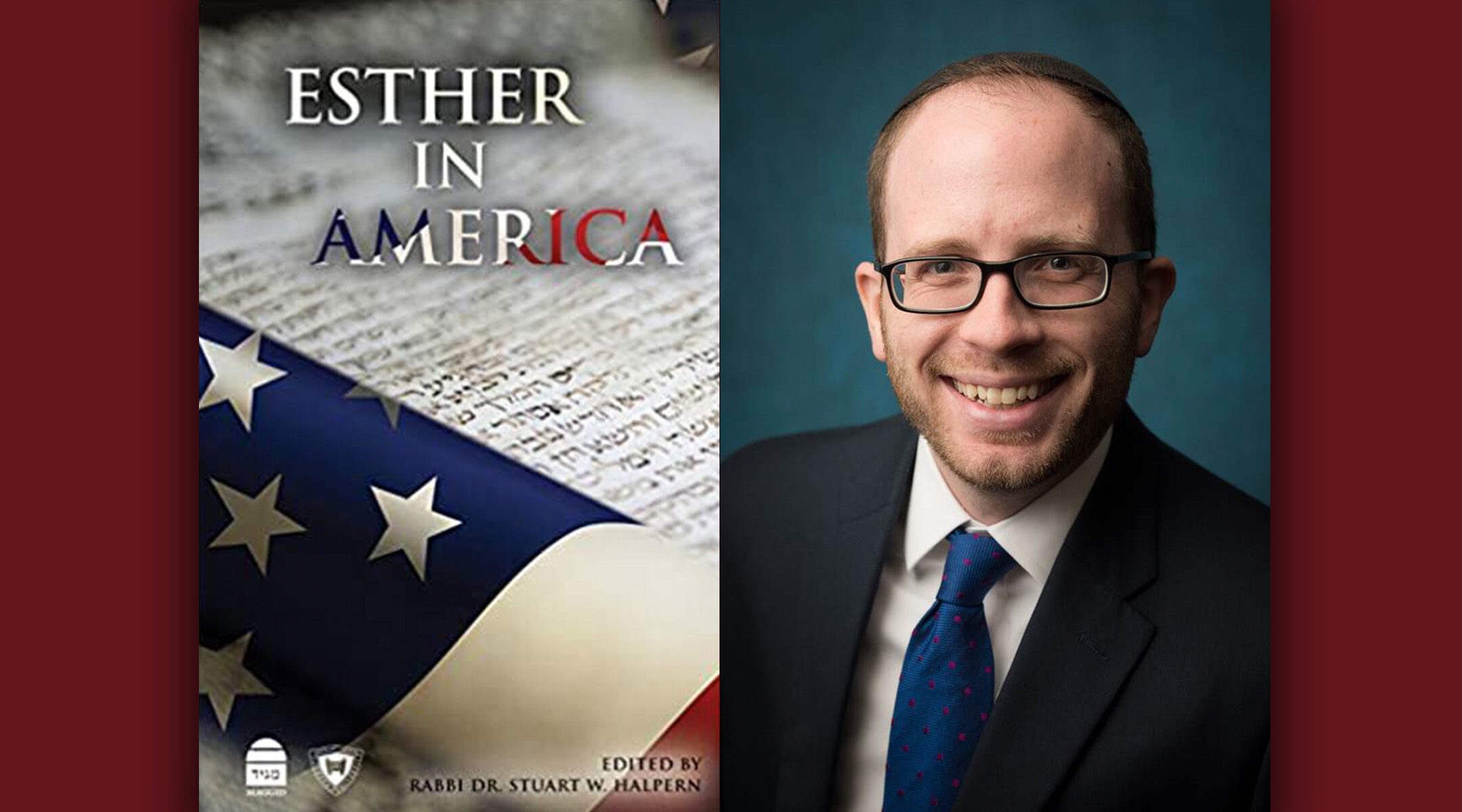

In his new book, “Esther in America: The Scroll’s Impact In and Impact On the United States” (Koren), Rabbi Dr. Stuart W. Halpern collects essays by 18 men and eight women showing how Megillat Esther has “inspired and impacted the American project since its very inception.”

Halpern is Senior Advisor to the Provost of Yeshiva University and Senior Program Officer of the Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought. He spoke to the Jewish Week from his home in northern New Jersey. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

When did you know the Esther story was rich enough to sustain a book of particularly American engagements with the story?

I was really energized by colleagues of mine who came out with a book called “Proclaim Liberty Throughout the Land: The Hebrew Bible in the United States.” It was a book of foundational American sources from the Puritans through Lincoln’s second inaugural address, side by side with the biblical verses that inspired them. I figured the next step was to take a deep dive into a particular biblical book and show the ways the Hebrew Bible have inspired the American project.

Dr. Eran Shalev, an Israeli professor, had written in his book, “American Zion,” that Americans thought of George III, before he was made famous by the “Hamilton” show, as an Ahaseurus, and the prime minister of England giving him bad advice as a Haman. I came across a book by Ariel Clark Silver, who’s a scholar and a member of the LDS Church, about Esther in American letters and how Nathaniel Hawthorne’s heroine Hester Prynne in “The Scarlet Letter” is essentially Esther. And once you know that you can’t unsee it.

I said, you know, wouldn’t it be fun to see if there’s really a full story to be told here from the colonial times to the modern era.

The story of a “hidden” Jew saving her people from destruction resonates with so many people in different ways.

I didn’t want to be Ashkenormative, which led to to the fascinating chapter by Dr. Emily Colbert Cairns on Saint Esther in South America, where at the push of the Inquisition crypto-Jews had to of course keep their Judaism secret. And the idea of a heroine with a secret Jewish identity: That was something that very much resonated with them. And so I’m excited about what I think is a diverse range of topics and themes, from Cotton Mather to Mordecai Manuel Noah.

He’s the 19th-century dreamer who wanted to build a Jewish promised land near Buffalo, N.Y.

One of the most overlooked but fascinating historical footnotes in American Jewish history. Fifty years after independence, Noah says, “I’m going to make a homeland for the Jews in this incredible land that has been so welcoming to me, so I’m gonna get my wealthy friend to buy Grand Island in upstate New York. I’m going to declare it a homeland for the Jews. I’m going to have a flotilla with animals on it, and I’m going to call it Noah’s Ark, and I’m going to invite the Native Americans” — he would have called them Indians — “to a Promised Land outside of Zion.” He and others, including Thomas Jefferson, thought for a brief period that the Indians might have been members of the 10 lost tribes. Now of course you know and I know that that the project was essentially doomed to fail from the moment he had the opening ceremony at an Episcopal church. But he was asking the question that you and I live with every day: “Can there be a viable Jewish life outside of the land of Israel?” That is obviously the core question of the Book of Esther.

That part of the story — about exile and Diaspora — I see that in essay after essay in the book. Esther and her uncle Mordecai are Jews living in this Persian kingdom, and the book can be read as a kind of guidebook on how to deal with powerlessness in the Diaspora. I’ve also seen it taught as a deep satire on the folly of even trying.

People who live in Israel offer that reading, that instead of the Kohen Gadol effectively wearing royal clothes and fasting and going into the inner sanctum [of the Jews’ own Temple], they’re subject to the whims of this kooky king and his nefarious advisor — and it’s Esther who has to put on royal clothes and go into the inner sanctum while fasting. There are dozens of other examples which effectively make the case that the book is satirical and essentially saying “all this has fallen upon you because you’re not in the land of Israel.”

The novelist Dara Horn has an essay in your book that gets at that in a distinctly American way, describing what American Jews sacrificed in terms of identity and authenticity when they changed their Jewish names, just like Mordecai and Esther have names that aren’t “Jewish.”

I feel that whenever we’re visiting the Holy Land, and I get into a cab and the cab driver says, “What’s your name?” and I say Stu, and they say, “What kind of Jewish name is Stu?” Names are a particularly easy way to identify this navigating of dual identities. Mordecai and Esther are, as many scholars have pointed out, pagan names.

Esther’s story has been constantly digested and refracted according to the gender politics of the day and the interpreter. The essays in your book run the gamut, from Puritan minister Cotton Mather’s “proto-feminist” interpretation, as you call it, to those who see her as a role model of women’s agency, to those who bristle because her power is based largely on her looks.

It’s fascinating how the same heroine can somehow inspire Sojourner Truth in the fight for women’s rights and for abolition, as well as those who held a “Queen Esther” beauty pageant at Madison Square Garden in 1933. In her essay, Dr. Erica Brown shows how Sojourner Truth comes to a women’s rights rally in New York that had been so infiltrated by disrupters that it became known as the “mob” convention. And in this fraught moment she gets up and, of all the things she could have quoted, she jumps straight into the Book of Esther, saying that just as Esther risks her life to advocate before the king, she, Sojourner Truth, is making her case before the president of the United States.

And then, of course, the notion of Jewish beauty is constantly in the news today, whether it is Natalie Portman or Winona Ryder saying something about not getting a role because they look too Jewish or people being surprised that they are Jewish. These kinds of remarks still court the question of what it means to think about beauty in Jewish terms. Bible scholars have noted that we very rarely know what people look like in the Bible, but we’re told that certain characters are good looking. And because the Bible only tells you about certain character traits when they play a role in the plot, Esther’s beauty becomes a kaleidoscope for views of thinking about Jewish conceptions of beauty and how it might be used in ways to advocate for one’s people.

In your chapter on Mather, and in Zev Eleff’s chapter on the late 19th century, contemporary clergy basically say that Esther is a role model because she helped wayward men become better behaved. That is both one kind of feminism, and exactly its opposite.

There’s a scholar at Shalem College named Orit Avinery who has a book that reads Ruth and Esther as feminists, and just when you are convinced she flips it and shows you the ways neither story is feminist. I definitely agree that you could read it both ways. I once gave a lecture on Esther and afterwards a woman said, “How dare you say that the story is feminist? That’s obviously anachronistic, and why are you even bringing that into this discussion?”

I said whatever I said to survive the conversation, but I think the idea of looking at these stories through a modern lens is something that’s religiously edifying and intellectually interesting. Part of what I tried to show is how it has always spoken to the current American moments, whether or not Esther has been taken to places that she was ever intended or expected to go. I find it personally inspiring, as a Jew and as a firm believer in the power of Hebraic ideas to inspire, that this story continues to resonate.

Does the fact that God never appears in the story add to its embrace by American thinkers of so many different ideologies and persuasions?

Yes, yes. We live in an age when we obviously don’t see the hands of God in our day to day. So when we feel under threat and we don’t have a temple to walk right into to seek solace, it’s an attractive and inspiring idea that it’s humans who create courageous actions on behalf of their people, particularly when I, like so many American Jews, can choose comfort over covenant. Choosing your people over being in the palace is a choice that so many of us are faced with day in and day out. And so I think it holds particular resonance for the American Jewish community, and as I try to argue, for Americans writ large.

What was your most surprising find when you were looking for contributions?

Definitely the beauty pageants. Everything has its own context, but here was the fascinating idea that, like you said, a heroic woman is taking initiative, has a story that has inspired so much good, and then she can essentially be pigeon-holed back into someone we should care about because of her looks.

The happy Purim story has a sort of “Game of Thrones” ending, in which the Jews are given permission to go out and slaughter their enemies. Was the ending of the book ever used against the Jews?

I haven’t seen it in the American context. The late scholar Elliott Horowitz has a book, “Reckless Rites,” which documents how Purim was used to justify violence by Jews. But you don’t really see people rioting in the streets, you know, breaking things to mark the defeat of the evil Haman. Discomfort with victory over one’s enemies is something that has become more and more common the greater distance we get from the Holocaust. The idea that we should feel bad when our enemies are defeated is something that more and more people are kind of leaning towards. But I don’t think we need to be ashamed that the tale is told in this way, whereby the Jews earn a resounding and inspiring victory and loyalty to one’s people ends up being protective of them and ensuring their long-term viability.

Do you see a difference in how gentile commentators and the Jews have used this story?

The relative common ground is the lack of overt religiosity. God is not mentioned. Prayer is not mentioned. On some level, the idea of individual heroism and loyalty, and the salvation provided by the actions of one person to their spouse or to their nation is something that’s obviously universalistic.

To get more in the weeds, it’s interesting to see how different Jewish denominations think about this book. Esther can be a barometer for what you want her to be: an assimilated Jew who, when push comes to shove, will stick out her neck on behalf of her people, or a pious Esther who, as the rabbis say [in Megillah 13a], had different servants come in every day to remind her when Shabbat is.

I can’t let you go without talking about Tevi Troy’s chapter on American First Ladies and other people with access to power and the ways they have been compared to Queen Esther.

When we started with the book, a couple of people said to me, “Oh, there will be a chapter on Ivanka, right?” And I said, no, that’s so not the route I want to go. As a presidential historian, Tevi traced a fascinating survey of how modern politicians used the story, from Bibi Netanyahu handing President Obama a copy of the Scroll of Esther in the middle of the Iran nuclear deal brouhaha, to Secretary of State Pompeo calling Trump a modern Queen Esther called to save the Jewish people from the Iranian menace. And then you have both Monica Lewinsky being compared to Esther and Hillary Clinton saying that Esther was her favorite biblical heroine. I found out that after Sarah Palin was picked to be John McCain’s vice presidential candidate, her pastor said that Esther was her favorite biblical figure.

Tevi also compares the dynamic of an effectively second-in-command who is unelected and has to navigate the other stakeholders in the palace, which is a fascinating prism for thinking about First Ladies and their own palace intrigue at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.