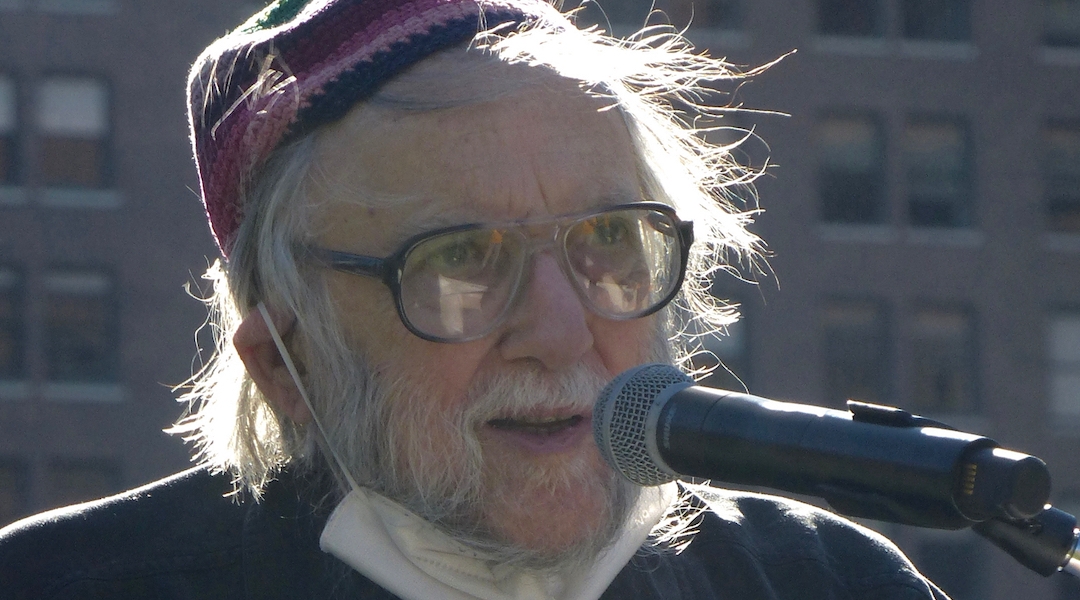

(JTA) — On the day after the 2020 U.S. presidential election, Rabbi Arthur Waskow gingerly mounted a small wooden stage at Philadelphia’s Independence Mall to address dozens of activists concerned that Donald Trump was trying to halt the counting of legally cast ballots.

At 87, the activist rabbi, who has been at the forefront of Jewish social justice struggles for more than a half-century, is in an elevated risk category for the coronavirus, and he wore a mask and kept his distance as he waited his turn to address the crowd.

When he did, he invoked Moses gathering the Israelites at the foot of Mount Sinai and the Jewish tradition which says that not only were the Israelites then alive present to receive the Torah, but all subsequent generations yet to be born were there as well.

“What he was saying was, this moment is so important that it will affect the future forever,” Waskow recalled later. “And he was right about Sinai — not only for the Jews, but for Christianity, for Islam and for people who now would say they were secular. And I think this election was core for the United States of America and even for the planet. It will affect the future for hundreds, maybe thousands of years.”

For months as the pandemic raged, Waskow had barely left his home in Philadelphia’s Mount Airy neighborhood — save for doctor’s appointments and demonstrations. And it’s not hard to see why Waskow considers the two on fairly equal footing when it comes to his overall well-being.

Not since Abraham Joshua Heschel marched with the Rev. Martin Luther King in Selma in 1965 has an American rabbi been as indelibly associated with the fight for justice as Waskow. Since his creation in 1969 of the “Freedom Seder,” a version of the Passover Haggadah that introduced contemporary liberation struggles into the ancient story of the Israelite escape from Egyptian bondage, Waskow has been among the leading voices bringing Jewish spiritual wisdom to bear on the progressive political agenda. And neither age nor a global pandemic has diminished his ardor for the fight.

In September, Waskow published “Dancing in God’s Earthquake,” the latest in a catalog of more than two dozen books, several of which have become Jewish classics. The new work runs through the litany of issues that have animated Waskow for decades — feminism, economic injustice and, most pressingly of late, climate change — all refracted through the lens of Waskow’s innovative readings of Jewish text and tradition. Two other books are in the works, even as Waskow keeps up a years-long commentary on the issues of the day delivered by email, often at a rate of several communications per week.

Waskow addresses a protest in Philadelphia the morning after the 2020 presidential election. (Rivkah Walton)

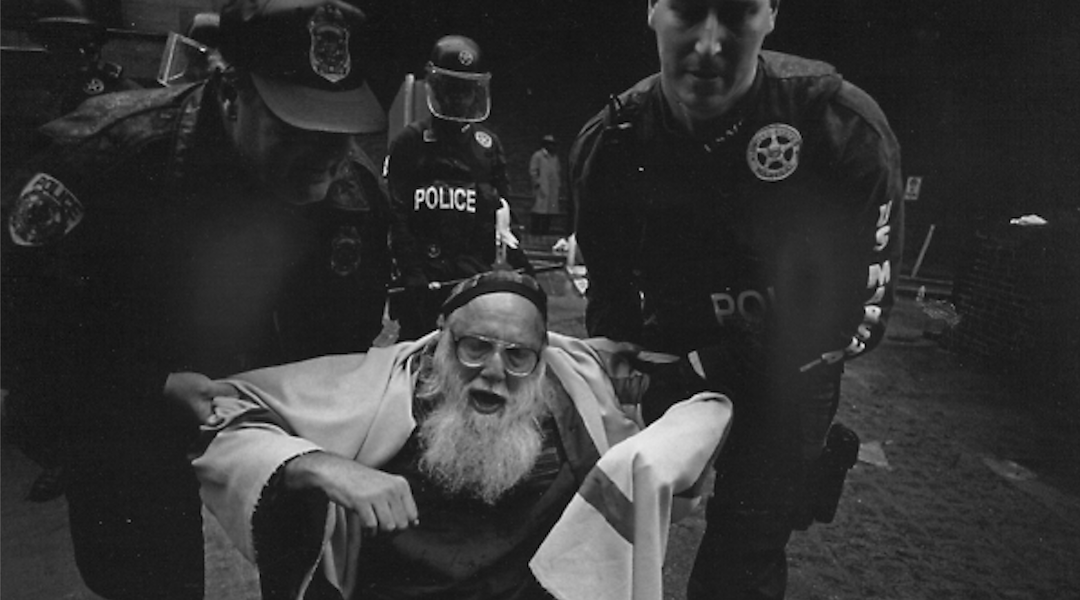

Nor has advancing age led Waskow to grow averse to getting himself arrested, which he has done more than two dozen times — he’s lost the exact count — since his first time while protesting a segregated amusement park in his hometown of Baltimore in the 1960s. In 2019, Waskow was arrested outside an Immigration and Customs Enforcement office in Philadelphia while protesting the Trump administration’s treatment of migrant women. He had been arrested in the same location, for the same reason, the previous summer.

Rabbi Mordechai Liebling, a fellow Philadelphia activist rabbi and the founder of the social justice training program at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, recalled an incident a decade ago when he and Waskow were protesting the Keystone pipeline at the federal building in Philadelphia. Liebling was arrested after jumping over a barricade in an effort to block the doors, but Waskow, then in his late 70s, couldn’t make it over.

“Arthur laid down on the floor and tried to wriggle under the barricade to block the door,” Liebling said. “He wasn’t going to be stopped.”

Waskow was destined for activism from an early age. Both his parents were politically engaged — his father was a labor organizer who had headed the Baltimore teachers union and his mother registered Black voters in the Maryland city’s neighborhood. Both were active with Americans for Democratic Action. His grandfather was a precinct organizer for Eugene Debs, the legendary unionist who ran for president five times as a socialist between 1900 and 1920.

“That was in my bloodstream,” Waskow said.

After earning a doctorate in history from the University of Wisconsin, Waskow went to work on disarmament and civil rights for Robert Kastenmeier, an influential longtime member of the U.S. House of Representatives. Later he became a fellow at the progressive think tank the Institute for Policy Studies. In 1970, he testified for the defense at the trial of the Chicago 7.

In 2004, Waskow was arrested in a nonviolent sit-down protest against passage of a federal tax bill that enriched what he called “the hyperwealthy” and imposed more burdens on the poor. He said the police arresting him and the other members of his group — about 150 in all — quietly agreed with him, and acted “caring and courteous” with them. (Courtesy of Waskow)

The trial was the first time that Waskow had worn a yarmulke in a nonreligious setting — the judge tried to have him remove it, but relented at the prosecutor’s urging. At the time, Waskow “was still wrestling with what this weird and powerful ‘Jewish thing’ meant in my life,” as he would write later. Though he had always observed Passover, Judaism had failed to seriously capture his attention until well into adulthood.

That changed on an April evening in 1968 as Waskow headed home to prepare for the Passover Seder. Federal troops were out in force to quell riots sparked by the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. just days before, and seeing a machine gun pointed at his block in the Adams Morgan section of Washington, D.C., Waskow had an intuition that it was Pharaoh’s army occupying his neighborhood.

That insight inspired Waskow to write the “Freedom Seder,” which referred to King and Mahatma Gandhi as “prophets” and introduced quotes from a range of modern thinkers alongside the traditional text, including Thomas Jefferson, Nat Turner and Eldridge Cleaver. The Orthodox Rabbinical Alliance of America denounced the work as “most offensive” for making radical changes to the Haggadah without rabbinic authority and quoting alleged anti-Semites.

“There’s no question, it was chutzpadik,” Waskow said, using a Yiddish expression that roughly means audacious. “I think it turned out to be holy chutzpah.”

Waskow had no real standing at the time to rewrite a classic of the Jewish canon, but he nevertheless found a ready audience. The following year, on the anniversary of King’s death, the Haggadah was used as a guide for a Seder in the basement of a Black church in Washington. Hundreds were in attendance and the event was broadcast live on the radio.

The “Freedom Seder” would be the first of many works Waskow would pen that reimagined Jewish tradition to speak more directly to contemporary concerns, initiating a movement that many Jews now take for granted. Passover Seders integrating the oppression of Uyghurs in China or the genocide in Darfur hardly raise eyebrows today. Nor is it uncommon to see rabbis in prayer shawls blowing shofars and being arrested at demonstrations. But in 1968, the idea that Passover had something to say about the American political situation was a revelation.

Waskow continued in this vein with his 1982 work “Seasons of Our Joy,” a New Age guide to the Jewish holidays (New Age became “modern” in subsequent editions). Written in the DIY spirit of “The Jewish Catalog,” the book reintroduced the earth-based, agricultural roots of the Jewish holidays decades before Jewish farmers and environmental activists would make such linkages seem obvious.

Arthur Waskow and his daughter Shoshana Waskow sang with Pete Seeger at the edge of the Hudson River in 1998 when his 65th birthday coincided with the end of Sukkot, as it had when he was born. He celebrated by leading the Earth-healing ceremony of Hoshana Rabbah to protest General Electric’s refusal to clean up the Hudson from cancer-causing chemicals it had poured into the river. Hundreds of Jews, a dozen Catholic nuns, an Iroquois spiritual leader, and Seeger joined the festival protest. (Courtesy of Arthur Waskow)

In 1982, when hundreds of Palestinians were massacred by Israel-aligned Christian Phalangists at Sabra and Shatila, Waskow was at a retreat center near Baltimore for Rosh Hashanah. Waskow took the front-page article on the killings from the Philadelphia Inquirer and chanted it as the haftarah at the morning service.

The following year, Waskow founded the Shalom Center in Philadelphia, initially to address the threat of nuclear weapons through a Jewish lens. Over time, the organization came to focus on other concerns, including Middle East peace, interfaith relations and climate change.

“He was almost a lone voice for a long time, really trying to bring Jewish values to the political situation,” Liebling said. “Heschel certainly had done this, and there were two or three other rabbis who did that well — Everett Gendler, some more. But they weren’t as radical as Arthur.”

Being a radical is something of a badge of honor for Waskow, who still gets a childlike gleam in his eye describing himself as a revolutionary. His decision to seek rabbinic ordination in 1995, when he was 62 and already teaching at the Reconstructionist seminary, was born of his recognition that the rabbinate was a revolutionary institution, a linchpin of the transformation of ancient Judaism from a faith based on temple rites to one of learning and prayer.

Judging by appearances, Waskow seems uniquely suited to the role of religious revolutionary. A burly man with a wispy white beard and an instinct for impassioned oratory, Waskow brings to mind the biblical prophets. A book he authored with his formerly estranged brother, Howard, relates how Arthur inspired fear as a younger man. And though his gait has slowed and he relies on a cane for balance, Waskow remains physically imposing. Photos of him at demonstrations in recent years show his capacity for summoning righteous fury in the face of injustice remains largely undiminished.

“People have said that I have softened him,” said Rabbi Phyllis Berman, Waskow’s wife of 34 years. “And I think that I have. And he has also toughened me. So both things are true. He said to me very recently, in a very precious exchange, that I don’t take any shit from him anymore. And I think I probably did for a long time. He is a frightening man when he’s angry. But I’ve learned to stand in the face of it in a much, much more profound way.”

Berman and Waskow met at a conference in 1982, some months after she read “Seasons of Our Joy” and sent Waskow a love letter, which he never answered. (It had been lost in the mail.) Berman confronted Waskow over the lapse and the two struck up a friendship. Four years later they were married and each took on a new middle name — Ocean — inspired by their shared love of the sea.

Waskow, in red, at a climate protest in Philadelphia. (Courtesy of Mordechai Liebling)

Oceans, or the rising levels thereof, are much on Waskow’s mind these days as he pours his energies into fighting climate change. Waskow devotes the first chapter of “Dancing in God’s Earthquake” to retelling the Garden of Eden story through an ecological lens before moving on to a range of suggested responses, from solar co-ops to increased carpooling to avoiding industrial meat.

In December, he published an article in Tikkun pushing his co-op idea, an initiative that Waskow believes not only can accelerate the switch to renewable energy sources but also, by emphasizing local cooperation, avoid the risk that a massive Washington environmental initiative would fall prey to America’s cultural divide. The noted environmental activist Bill McKibben gave it a shoutout in his New Yorker column.

But as urgent as Waskow believes climate change to be, he hopes his legacy will be a deeper shift in Jewish theology — and by extension in the Jewish psyche. Waskow believes that modernity has presented Judaism with a challenge on par with the one faced by the ancient rabbis following the destruction of the Temple. That challenge, reflected in the cascading crises now facing humanity, will require a profound transformation in religious thought — from one centered on serving God as a ruler or king to a more ecological worldview that sees all of creation as part of an interbreathing whole.

“Modernity did to us what Rome, and before Rome Egypt and Babylon, did,” Waskow said. “And the question is now, has modernity gotten so powerful, and so uncaring, and so uncontrollable, it’s going to wreck the whole joint before we can create an effective response. Or can we create an effective response? And that’s what I’ve been trying to do.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.