WHEELING, W.Va. (JTA) — Surrounded by silver crucifixes and Christmas ornaments, Samuel Posin and Joan Berlow Smith sell vintage jewelry and myriad tchotchkes at their church-turned-boutique gift shop in this city.

This is not the kind of place you’ll find many Jews. In this deeply rural state where just over half of all voters identify as Christian evangelicals, one longtime rabbi estimates that fewer than 1,200 Jews are scattered among West Virginia’s 1.8 million residents.

Yet born and raised in Wheeling, Posin, 62, prays three times a day, eats only kosher food and keeps Shabbat – making him one of less than a dozen observant Jewish adults in all of West Virginia, by his own estimate. He credits a life-changing trip to Israel a decade ago for lighting his spiritual spark.

“I spent seven weeks at Rabbi Akiva Yeshiva in Jerusalem and immediately became religious,” Posin said of his 2010 trip to visit his sister, who had moved to Israel.

About five hours’ drive south of Wheeling — on a winding mountain road in the heart of Appalachian coal country — Elisse Jo Goldstein-Clark, the proprietor of a bed-and-breakfast called the Elkhorn Inn & Theatre, showcases another unlikely Jewish home.

Every Chanukah, she displays an 8-foot-high menorah in front of her historic inn, which is filled with railroad and coal-mining memorabilia. Each of the hotel’s 14 guest rooms has its own mezuzah.

West Virginia is one of America’s poorest states, located in a part of the country that long has been in decline. But the proud Jews you’ll find here show how Judaism endures even in the unlikeliest of places and what Jewish living looks like in rural America.

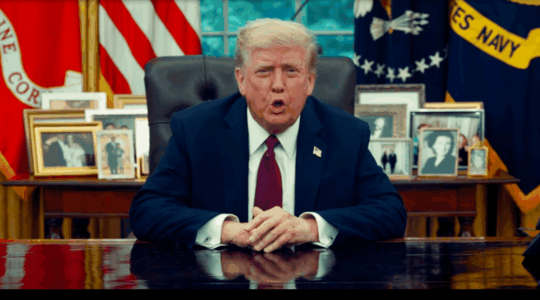

Majorities in all 55 counties in West Virginia voted for President Donald Trump in the 2020 election. (Larry Luxner)

Goldstein-Clark is a rare Jewish transplant to West Virginia. Originally from New York, she moved to Jerusalem years ago and served a stint in the Israeli army before returning to the U.S. She ended up in the town of Landgraff after her husband — a disaster-response official whom she met in New York after the 9/11 attacks in 2001 – was deployed there to address severe flooding in West Virginia in 2002. The couple decided to stay, and a year later opened their hotel in a restored 1922 coal miners’ clubhouse.

“For 18 years, the New Yorker in me never stopped whining about how incredibly rural we were,” Goldstein-Clark said. “But living in West Virginia has turned out to be the greatest blessing in my life.”

Driving around West Virginia these days, “Make America Great Again” billboards are as plentiful as gun shops. President Donald Trump defeated Joe Biden in all 55 West Virginia counties in November’s elections. The state is so staunchly conservative that its Republican governor, Jim Justice, earlier this year urged like-minded rural counties in Democrat-controlled Virginia to secede from that state and join his.

Yet West Virginia is in serious trouble. It has America’s lowest percentage of college graduates, fourth-highest incidence of poverty, highest rate of opioid overdose deaths and fourth-oldest population. Most troublesome, the state is the only one whose population consistently declines year after year. It has been on a downward trajectory since its peak shortly after World War II.

Back then, when coal was king, the state was more populous than Florida, and synagogues and Jewish communities thrived in small towns and cities from Beckley and Bluefield in the south to Wheeling and Weirton in the north. Most of these Jews were descended from Eastern European peddlers who flocked to West Virginia around the turn of the 20th century and became prosperous merchants and retailers.

West Virginia once had eight cities with vibrant Jewish congregations, according to Posin, whose family dates back four generations in Wheeling.

Samuel Posin and Joan Berlow Smith, members of Wheeling’s small Jewish community, run a jewelry shop out of a converted 1932 church building. (Larry Luxner)

But most of the communities that thrived from the 1890s to the 1970s virtually disappeared by the 21st century.

“From today’s standpoint, it is hard to believe that thousands of Jews lived in the coalfields during that 80-year time span, that Jewish life once flourished there,” historian Deborah Wiener wrote in “Coalfield Jews: An Appalachian History,” published in 2006. “Because of present reality, it is easy to look on their story as an oddity of history.”

Back in 1950 McDowell County, where innkeeper Goldstein-Clark resides, had 100,000 people, a kosher butcher and synagogues in Keystone, Welch and Kimball. Today the county’s population has sunk to 17,000, and McDowell has the shortest life expectancy and highest drug-related death rate of any county in the United States.

“When we moved here in 2002, we were told that the last Jews had moved to Bluefield, and that I was the only Jew left in the county,” Goldstein-Clark said. “That hasn’t changed.”

The state’s Jewish population peaked at about 6,000 in the 1950s, according to Rabbi Victor Urecki of B’nai Jacob Synagogue in Charleston, the state’s largest city (46,000 residents, down from 86,000 in 1960). He estimated that the current population of Jews in the state may be around 1,200.

“The attrition continues throughout the state, and every community of faith is equally affected,” said Urecki, one of West Virginia’s six rabbis. “The lack of young people is a problem in every congregation.”

Gun shops like this one in Beckley are a common sight throughout West Virginia. (Larry Luxner)

Rabbi Zalman Gurevitz, who runs the Chabad center at West Virginia University in Morgantown, said it’s not just Jews.

“Anyone who has graduated college is going to have a hard time,” he said. “There’s nothing to come back for.”

The Morgantown Chabad serves about 100 to 150 Jewish students at WVU. Since the pandemic hit, Chabad has not held in-person Shabbat services, though it offers takeout kosher Shabbat dinners that include challah, grape juice, matzah ball soup and a main dish. On the High Holidays, Gurevitz hosted about 20 people in an outdoor tent.

“Obviously it’s challenging to have a permanent presence in a place where Jewish communities are getting smaller and smaller,” said Gurevitz, who with his wife, Hinda, has seven children.

Georgia Katz DeYoung grew up in Martinsburg, a town in West Virginia about 90 minutes from Washington, D.C. She went away for college but came back to manage her father’s downtown department store, George Katz & Sons.

At its peak in the early ’50s, Martinsburg had 60 Jews. Its synagogue, Beth Jacob Congregation, opened in 1912 in a former church as an Orthodox shul, became Conservative when it moved downtown in 1952 for the convenience of local merchants, and turned Reform before closing down in the late ’60s.

“As industry began to fade, the merchants also left Martinsburg,” said DeYoung, who now lives in New York. “There were two malls on the outskirts of town, and the chains and restaurants followed, so the downtown became decimated. I could see the Jewish population was getting smaller, and finally they gave up. Last time we were there it had become a church.”

Robert Judd started in April as the rabbi of B’nai Sholom in Huntington, W.Va., but has yet to hold an in-person service because of the coronavirus pandemic. (Larry Luxner)

The pandemic’s silver lining

The coronavirus pandemic has killed more than 300,000 Americans and shuttered synagogues across West Virginia and the world. But it has also injected new life into isolated Jewish communities through online prayer services.

At B’nai Sholom Congregation in Huntington, not far from the point where West Virginia, Ohio and Kentucky meet, nearly 300 people tuned in for online services on Yom Kippur. That’s more than usually attend in-person services at the 111-member congregation.

“This is a tight-knit community here,” said Rabbi Robert Judd, who joined B’nai Sholom in April but has yet to hold an in-person prayer service due to the pandemic. “Nobody gave up, nobody threw their hands up in the air. Instead they adapted to technology very quickly. And from what I can tell, people seem to be liking it.”

Wheeling, once the nation’s wealthiest city on a per-capita basis, is home to the state’s oldest synagogue, Leshem Shomayim. Now known as Temple Shalom, the congregation was formed in 1849, even before West Virginia was a state. A century later, services were led by the Zionist luminary Rabbi Abba Hillel Silver.

Now Temple Shalom, with 80 member families, is America’s smallest Reform synagogue with a full-time rabbi; his name is Joshua Lief. About 70% of Wheeling’s Jews marry outside the faith. The last Jewish wedding here was 12 years ago.

When the pandemic hit, Lief began broadcasting daily Torah lessons via Facebook Live. Temple Shalom typically draws about 90 worshippers for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur services, but this year some 350 people tuned into the synagogue’s online services.

“We were forced to figure out how to do this,” Lief said. “Because of the pandemic, we’ve actually increased our level of activity.”

Temple Beth El, a small cinderblock building built in 1935, serves the few Jews left in Beckley, a former coal-mining town in southern West Virginia. (Larry Luxner)

In Charleston, Urecki says B’nai Jacob has not missed a virtual minyan or Shabbat observance since holding its first Zoom service on March 21, which Urecki broadcast from his synagogue’s sanctuary.

“That 5:45 minyan every evening has created a virtual community for people who need community now more than ever,” Urecki said. “Many people have left West Virginia but consider B’nai Jacob their eternal homes, and our online Torah classes are bigger than they’ve ever been.”

Yet Urecki wonders what the long-term future holds for West Virginia’s few Jews.

“I’ve been hearing about decline for decades, and I try to push back against this feeling of helplessness,” he said. “We’ve got to find a way to engage younger people, but we have not found that secret sauce yet.”

West Virginia has seen its share of anti-Semitism and bigotry. Its most celebrated politician, the late Sen. Robert Byrd, was a proud member of the Ku Klux Klan as a young adult. A year ago, more than 30 West Virginia correctional academy trainees gave a Nazi salute in a class photo; they were fired. Earlier this year, a local state senator, Robert Karnes, wrote a Facebook post accusing Holocaust survivor and financier George Soros of having “made his fortune selling Jews to the Nazis.”

Yet local Jewish leaders said they feel comfortable here. Urecki said the vast majority of Christians he encounters are deeply respectful of Judaism. When he first arrived in Charleston 35 years ago to take up his new post at B’nai Jacob, Christians greeted him with “shalom” on the streets, and local ministers began calling to see if he could speak at their churches about Judaism.

Following the Tree of Life synagogue massacre two years ago left 11 Jews dead in Pittsburgh, an hour and a half north of Morgantown, Chabad’s Gurevitz said many local Christians reached out to him to offer condolences.

Support for Israel is also a deeply held tenet of evangelical Christianity in West Virginia.

“This is America, and there are obviously anti-Semitic groups in West Virginia, too. But I don’t think it’s more or less than any other place,” Gurevitz said.

“Personally I feel very safe here. And I would like to believe that if someone tried to hurt us, the community would protect us.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.