MYSORE, India (JTA) — From the flashing outdoor lights that deck out Park Street, to the bustling pop-up Christmas market at the central rotunda of the sprawling New Market, Christmas has always been a celebratory affair in Kolkata.

While this year celebrations are toned down due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the damaging after-effects of Cyclone Amphan that hit the city in May, Isaac Nahoum, a Jewish baker who has seen business tumble from more than 300 customers a day to a mere 30 on average, is not worried. The Christmas rush is still coming through.

“This was a big setback. Fortunately, we have the resources to carry on,” he said of his family-owned business, Nahoum & Sons, an iconic 118-year old Jewish bakery. “And, as I’ve said before, it’ll pick up next year.”

Known for its delectable fruit cakes and its selection of Christmas baked goods, Nahoum & Sons is a testament to Kolkata’s once significant Baghdadi Jewish community, of which less than 20 members remain.

“With the passage of time, the Baghdadis left India because they weren’t sure how things were going to be. And gradually the migration carried on,” Nahoum explained. “I left in 1951, when there were about 1,500 Jews left in Kolkata.”

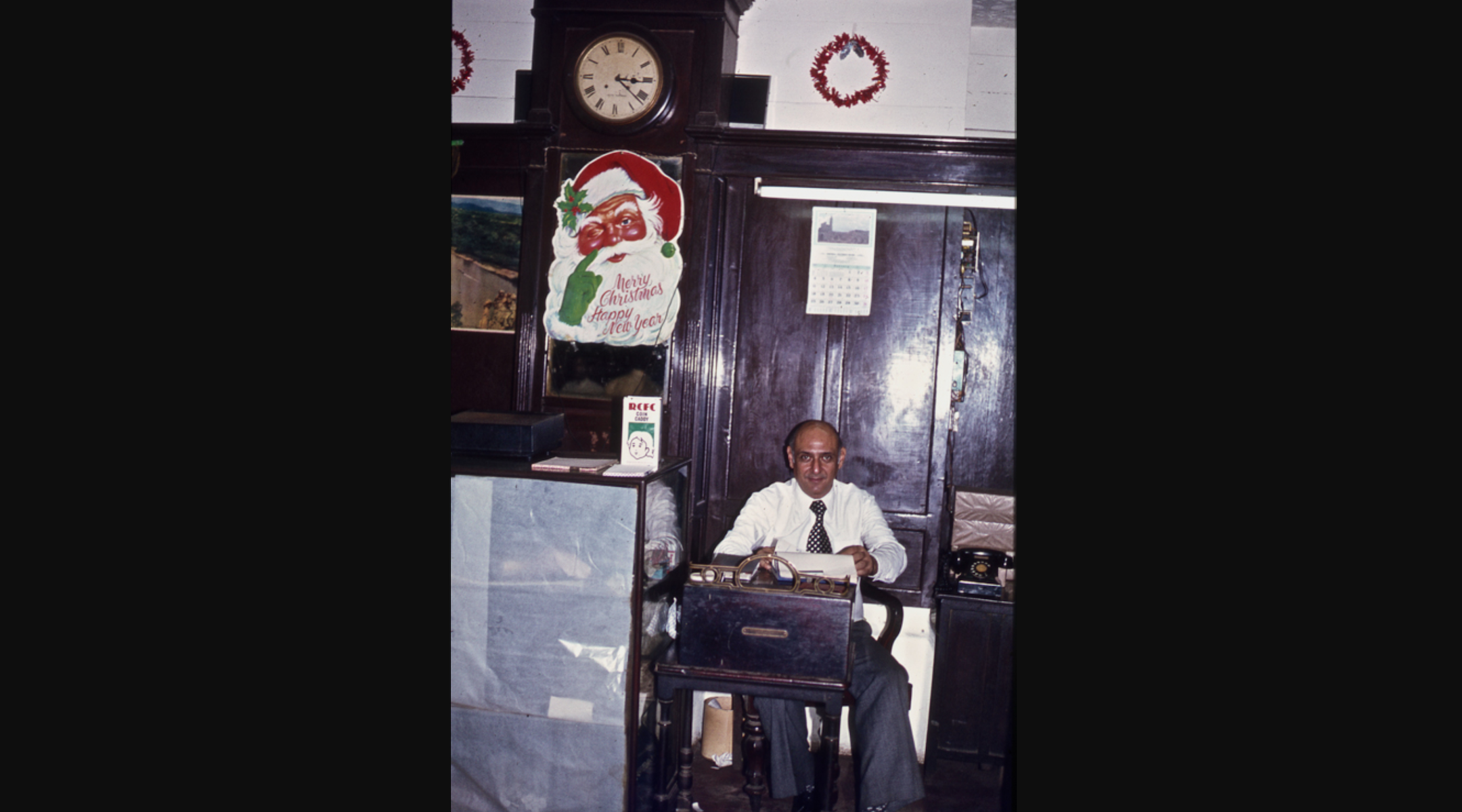

From the antique teakwood counters that hold a delectable mix of sweet and savory confections to the beloved family recipes passed on from one generation to the next, stepping into the century-old storefront, located in Kolkata’s vibrant New Market area, transports you to a bygone era.

“We’ve not changed the inside of the shop since 1902. The ceilings came from Italy and the showcases, I believe, came from Belgium,” Nahoum said.

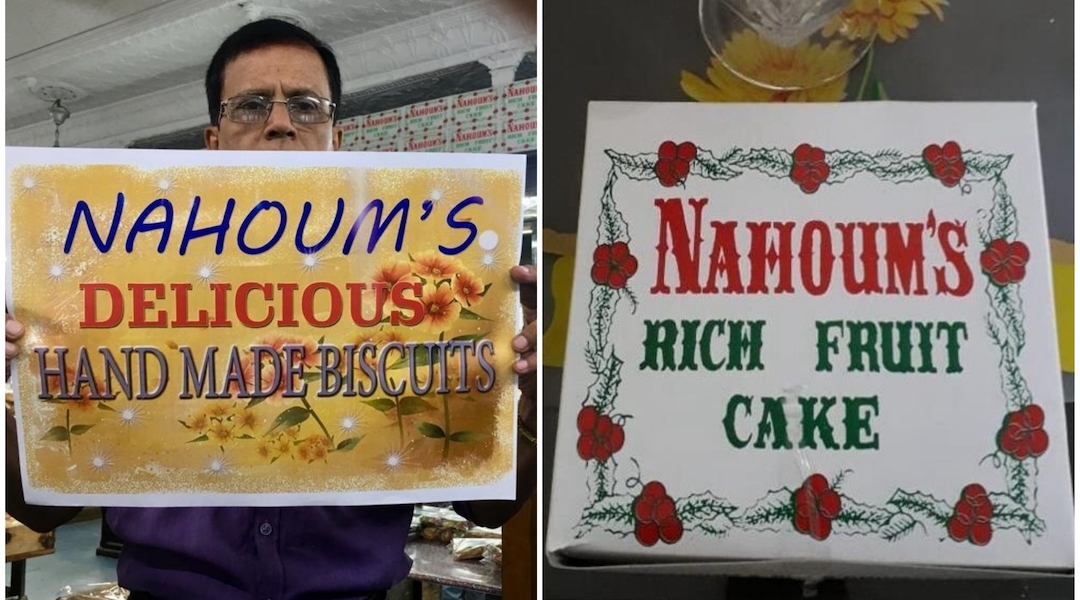

Isaac Nahoum says the quality of the butter and other ingredients the bakery uses is what keeps its products in demand. (Isaac Nahoum/Nahoum & Sons)

Nahoum & Sons has remained a family operation ever since it was first established by Isaac’s grandfather, Israel Nahoum, who moved to Kolkata from Baghdad in the mid-1800s. “When my dad, my uncles and my grandfather no longer did the business, my brother Norman took it over. He and my brother, Solomon, ran it for about 65 years. My brother David joined them along the way, and ran it until he passed away in 2013.”

The capital of West Bengal, India’s eastern state, Kolkata — or Calcutta, as it was known until 2001 — has long attracted a diverse mix of residents due to its strategic location along the left bank of the Hooghly River. In “Origin and History of the Calcutta Jews,” author Isaac S. Abraham notes that the first Jews arrived in Kolkata, then capital of British India and primary hub of the English East India Company, in the early part of the 19th century.

Christmas is a spectacle in Kolkata, even in this year amid the pandemic. (Avishek Das/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)

In part fleeing persecution in Baghdad and parts of the Middle East, the Baghdadi Jews — or Baghdadis as they came to be known — found India to be a land of tolerance where they could not only practice their religion freely but thrive as traders and merchants.

The Jewish community in Kolkata peaked during World War II, with about 5,000 Baghdadi Jews contributing significantly to the city’s growth and development, building lavish mansions, three synagogues, two schools, and setting up flourishing businesses like the city’s old stalwart, Nahoum & Sons.

A selection of some of the Nahoum & Sons pastries. (Isaac Nahoum/Nahoum & Sons)

As a youngster, Nahoum recalls his dad and uncles having a predominately European and Anglo-Indian clientele. But things have changed since then. “Now our customer base is mostly Hindu Bengalis, Muslims, Christians, and Chinese,” he said. “We’ve been fortunate that the population has grown to adapt to our items.”

While the store receives year-round patronage for its 140 fresh-baked products, including about 40 different handmade biscuits such as ka’ak — a savory caraway cookie that’s a Baghdadi Jewish specialty — it’s the bakery’s renowned rich fruit cakes that draw the crowds during Christmas.

The fruit cakes — the recipe is a trade secret — have been a popular offering since as far back as Nahoum can remember.

“When the archbishop of Canterbury, Geoffrey Fisher, came in 1966, he was a guest at Covenant House and they ordered our fruit cakes there for tea,” Nahoum recalled. “And he said, ‘You know, I’ve never had such a delicious cake.’ Now coming from an Englishman, who was entertained by the elite in England, that was a tremendous remark.”

(Isaac Nahoum/Nahoum & Sons)

Unlike India’s Cochin Jews, who emigrated due to the formation of the state of Israel, for Baghdadis it was India’s independence that proved to be a catalyst for emigration. The had an allegiance to the British and did not think they would succeed in the new India. Many, like Nahoum, ended up migrating to the United Kingdom, as well as Australia, Israel, and Canada.

But he would return.

“When my brother David passed away, I decided I would take up the mantle and run the business. We’ve stuck to the original recipes that my grandfather had,” explained the 85-year old Nahoum, who initially moved to England but now splits his time between Israel and Kolkata. “But, we also moved with the times to have more savory-type things like cheese samosas and chicken patties. I also introduced fish pantras (fried-stuffed savory crepes),vegetable chops and egg chops to the menu.”

Nahoum believes that the bakery owes its continued success to one key principle: never compromising on quality.

“Our ingredients, the butter, the nuts and whatever else goes into our products is all top quality. That’s why we’re so famous,” he said. “We’re good because we’re old. And we’re old because we’re good.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.