EAST POULTNEY, Vt. (Bennington Banner via JTA) — The autumn leaves crunched underfoot as Netanel Crispe walked uphill toward the northwest corner of the small cemetery. He stopped and examined a toppled headstone.

“The last time I was here this was standing up,” he said, regarding the weathered, gray stone. “At least it hasn’t broken.”

Crispe brushed away the leaves to reveal a carving at the top of the stone: two raised hands, the gesture used in the delivery of the Birkat Kohanim, Judaism’s priestly blessing.

This is the grave of Marcus Cane, who died on Nov. 13, 1874, and the raised hands are an indication that he was a kohen, a descendant of the sons of Aaron who served as priests in the Temple in Jerusalem.

Cane was a pioneer, one of the first German Jews who made his way to settle in the Slate Valley along the New York-Vermont border in 1868. These families established Vermont’s first Jewish community here in Poultney and left behind this largely forgotten place, the oldest Jewish cemetery in Vermont.

Before this summer Crispe, 18, a senior at Burr and Burton Academy in Manchester, was unaware that the cemetery existed. Now he’s leading an effort to restore and preserve the site.

“I decided it’s my responsibility to honor these pioneers and preserve their history because it’s vital to the history of our state,” Crispe said.

Crispe first learned of the cemetery while doing some metal detecting in town on behalf of a historical society.

“I came across a house that I was told was a synagogue,” he said. The family who owned the house “mentioned that there was a Jewish cemetery in town, and I was blown away because I had no idea.”

As both a 10th-generation Vermonter and an Orthodox Jew, Crispe is keenly interested in the history of Jewish life in the Green Mountain State.

“There are not many Jews in the area, so every time I meet one, it’s amazing,” he said.

The homeowner gave Crispe directions to the cemetery, but even so it was difficult to find.

“This was all grown up,” he said, waving his hand toward the entrance, “and I couldn’t even see the gate. But I finally found it on my third attempt.”

Expecting that it might be a marked-off corner of a larger burial ground, as is the case for many other Jewish cemeteries in Vermont, Crispe was “shocked” to find that it was a full, half-acre cemetery.

“And then I was really just disappointed to see how so many of the older stones are fallen down, broken, although many of them are in good shape,” he said.

The cemetery contains some 60 to 85 graves – there are no conclusive records. Most of the graves date from the 19th and 20th centuries. A handful, parts of family plots that date back decades, are more recent. Cane was the first person buried here, and his wife, Elisa, was the third.

Who were these settlers, and where have their descendants gone?

“Those were the two big questions that I was asking myself as well,” Crispe said.

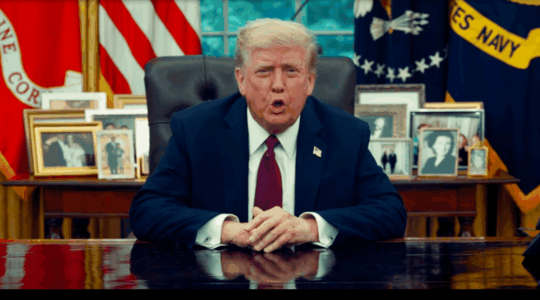

The oldest Jewish cemetery in Vermont was created by Jewish immigrants from Germany in the 19th century. (David LaChance/Bennington Banner)

His research led him to “’Members of this Book’: The Pinkas of Vermont’s First Jewish Congregation” by Robert S. Schine, a professor of Jewish studies at Middlebury College. A pinkas is a notebook, a record of events kept by a Jewish community, and Poultney’s pinkas had somehow survived, discovered in a used bookstore in Denver in 1966.

Schine writes that he had written to the American Jewish Archives at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in Cincinnati looking for any information about the Jews of the Slate Valley. The one item in the collection was the pinkas, written between 1867 and 1874 in German, with Hebrew and English bits intertwined.

Through the pinkas, Crispe learned that Poultney’s Jews had arrived from Germany around the time of the Civil War, drawn to the area’s booming slate industry. Predominantly peddlers in Europe, these new Americans became the shopkeepers, tailors and grocers for Poultney and Fair Haven, as well as Granville, New York, and environs.

“They were peddlers traveling around just with whatever they had on their back and their small skills, finding jobs here and there, but when they came to America, this was like a new life for them,” Crispe said. “They established and basically became a strong Jewish community here.”

The center of the new community was Poultney, where an upstairs room in the house owned by Isaac Cane, one of Marcus’s sons, was used for services. The congregation purchased a Torah, and later a second, from New York, and bought a half-acre of land from the Union Church to serve as its cemetery.

The history of the Jews of Poultney mirrors that of the slate industry itself, which went through booms and busts before collapsing during the Great Depression in the 1930s. By the 1890s, the Jewish community had disbanded. Some went to Rutland, others to New York, and still others to Ohio and the Midwest.

Crispe has been unable to find any further traces of the founders of the Poultney Jewish community. However, he has made contact with 15 to 20 members of families who came later.

“They’re just so happy to see that something’s being done and that their family hasn’t been forgotten in this way,” he said. “It’s been incredible hearing their stories, seeing the pictures they’ve been able to send me and placing a face on the stones, really being able to connect with these people.”

There are unanswered questions, among them the disappearance of both Torahs. Crispe said it’s possible that one was taken by a member of the congregation when he moved away, and that the second might have gone to a congregation in Rutland. The deed for the cemetery has long gone missing – “no one has the slightest clue where it might be, or if it still even exists,” he said – and so the town has taken responsibility for the site.

Crispe has a threefold plan: Restore and preserve the cemetery and all of its stones; create a fund to ensure that it can be maintained in perpetuity; and obtain official recognition of the cemetery’s historical status.

“I’m applying for a state historic marker to be placed here, and I want to get a nice gate – if we can raise the funds – that says Poultney Hebrew Cemetery, which is what it’s referred to,” he said.

“I’ve been connected with different historical societies, museums, the town of course, and different Jewish communities around the state. It’s a collective effort.”

Crispe has established a GoFundMe account – Save Vermont’s Oldest Jewish Cemetery – which had raised nearly $7,000 by early December.

Ideally he would like to add to the cemetery a genizah, a place for the proper disposal of worn-out or damaged Jewish religious items.

“I’ve contacted different rabbis in the state and most synagogues don’t actually have one,” he said. “They would love to have something like that available.”

“Really the main goal of the project is to reunite the Jewish communities of Vermont, bring together the Jewish life with the secular life and the communities of Poultney and the surrounding areas, and really just bring people together with a great kind of goal and mission in these troubling times.”

Crispe has dedicated himself to helping to preserve the state’s historic places. They’re not as secure as some Vermonters may think, he warns.

“Although we have so many historic buildings, and you see history everywhere around us … we’re losing it every year because there’s no laws preventing it,” he said. “If we lose our history, we lose our identity.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.