AMSTERDAM (JTA) – For the past two decades, a conflict has been slowly escalating in the Netherlands over the wintertime custom of wearing blackface ahead of St. Nicholas Day, the pre-Christmas festival honoring the saint who inspired Santa Claus.

Opponents of the custom say the portrayal of the saint’s sidekick, Black Pete, in processions and parties leading up to the Dec. 6 holiday is racist. Proponents resist what they see as censorship of an ancient tradition that they believe not only doesn’t demean Blacks, but is a celebration of them by a famously tolerant Dutch society. Clashes over the issue in recent years have occasionally turned violent.

This year, the Jewish Historical Museum in Amsterdam is wading into the debate with a new exhibition that features material that some hope might finally settle the question of whether depictions of Black Pete are racist. Its decision to address the subject is a politically sensitive one and the museum’s director is clear that his institution is opposed to the custom.

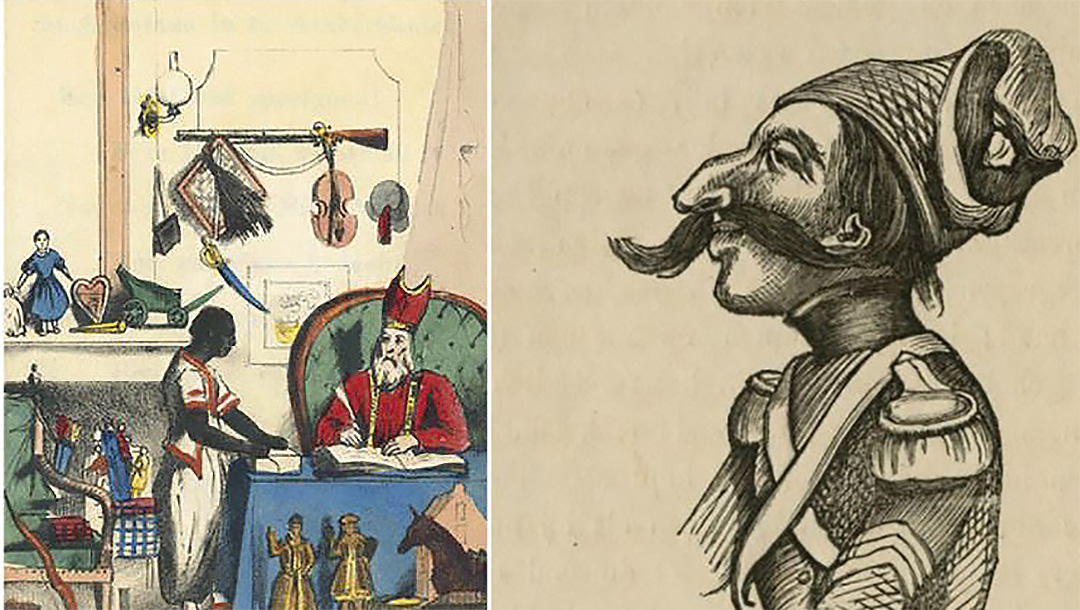

The exhibit shows that Jan Schenkman, a teacher who in 1850 published the first illustrations of Black Pete in a children’s book, also was the author of a popular series of booklets about a hook-nosed Jewish soldier called Levie Mozes Zadok. Titled “Levie Zadok and Black Pete: Two Caricatures,” the museum display is based on a book published last month by historian and journalist Ewoud Sanders titled “Laughing about Levie,” the first to examine Black Pete in light of Schenkman’s anti-Semitism.

“It’s proof that this tradition isn’t just racist, but that it’s actually rooted in racism,” Sergio Berrenstein, a Dutch anti-racism activist, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. (Berrenstein is not Jewish.)

The booklets showcased at the museum, written in the form of letters from Levie to his mother, begin with a satirical note in broken Dutch from Levie to his “mammele,” a Yiddish term of endearment for mother. Following the success of the first booklet, Schenkman penned another in which Levie boasts about selling tent parts to freezing soldiers during the Siege of Sebastopol in 1854. It came with a grinning caricature of Levie depicted with an enormous hooked nose and a bushy mustache.

Some 50,000 copies of the booklet were printed – “a figure that in 19th-century terms was huge and a testament to the letters’ enormous popularity,” said Emile Schrijver, the director of the Jewish Historical Museum.

The Levie booklets are not widely known today, according to Robert Vuisje, a Jewish author who has explored Jewish-Black relations in his writings and is a prominent critic of the Black Pete custom.

“It shows mainly a shift after the Holocaust in the boundaries of how Jews can be treated in popular culture,” Vuisje told JTA. “And it also shows that the boundaries have not shifted enough on how Blacks can be treated.”

An early depiction of Black Pete, left, by the Dutch author Jan Schenkman in the 1850s, and a caricature of the cowardly Jewish soldier Levie Zadok. (Courtesy of the Amsterdam Jewish Historical Museum)

Schenkman went on to write two more Levie booklets, at which point the series became so popular that it took on a life of its own, with fans circulating their own versions. Poems about Levie followed (“as bombs fly by his eyes, our friend Levie sat tight when in fact he had to fight”), along with illustrated comic book strips. In one of the latter, from 1855, Levie is depicted wearing makeup to resemble a “bushman” – a reference to Africans that at the time were making appearances at fairs in France. It was the first depiction of a white person wearing blackface in Dutch literature, according to the museum.

By the 1860s, Levie had grown so well-known that Dutch bakers were selling Levie-shaped gingerbread, complete with an enormous nose, the exhibition shows.

“Levie was a 19th-century hit,” said Schrijver, who also runs the Jewish Cultural Quarter of Amsterdam, which comprises the museum and several other Jewish institutions.

By comparison, Schenkman’s depictions of Black Pete were far more polite. His 1850 children’s book “St. Nicholas and his Aide” depicts Black Pete merely as a Black man walking alongside the horse-riding St. Nicholas. The first depictions of Black Pete feature none of the characteristics that were later added to the character, possibly by advertisers, such as exaggerated red lips, earrings and clownish costumes. Proponents of Black Pete often point to this as proof that the character isn’t intrinsically racist.

The subject today is politically sensitive. On Saturday, four people were arrested in the eastern city of Venlo after clashing with protesters opposed to the Black Pete custom. Last year, anti-Pete activists were besieged by counterprotesters inside a school building, which the attackers vandalized by smashing windows and setting off firecrackers.

While Schrijver warns about judging a 19th-century cultural phenomenon by present-day standards, he says the museum’s stance is transparent.

“Yes, we’re coming down on the side of the Black Pete opponents by choosing that as a topic,” he said. But the exhibition’s main contribution to the debate is in “showing that, unlike what many Black Pete advocates claim, this is not an ancient tradition but something from the 19th century, and that it’s part of a broader context in which people saw no harm in offending whole groups of people.”

The exhibition has received considerable media attention in the Netherlands, exposure that Berrenstein, the anti-racism activist, says is important because it “sets the record straight” on Black Pete.

“It’s a significant find because it goes down to the root of the problem,” he told JTA.

But, he added: “It will inform those who wish to be informed. I’m under no illusions of its ability to reach those who do not with that.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.